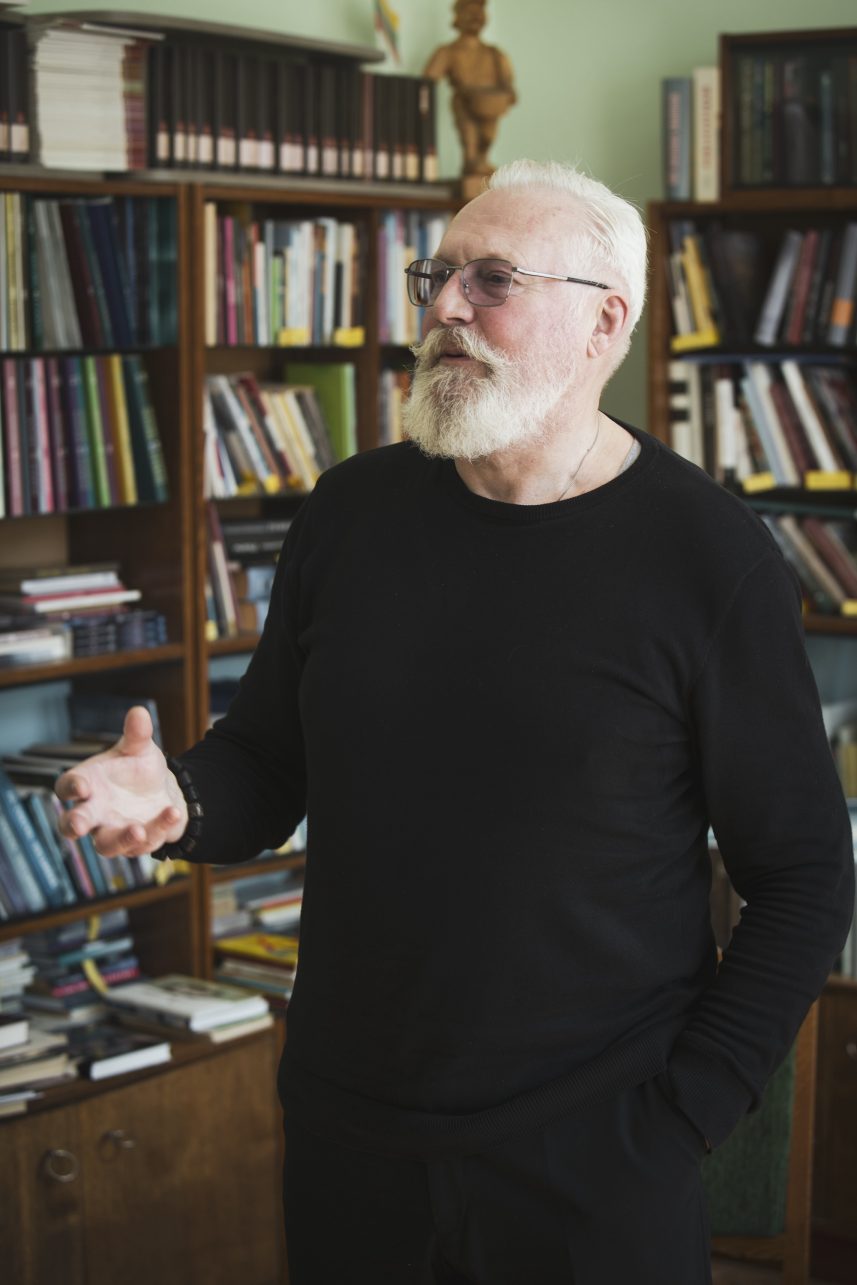

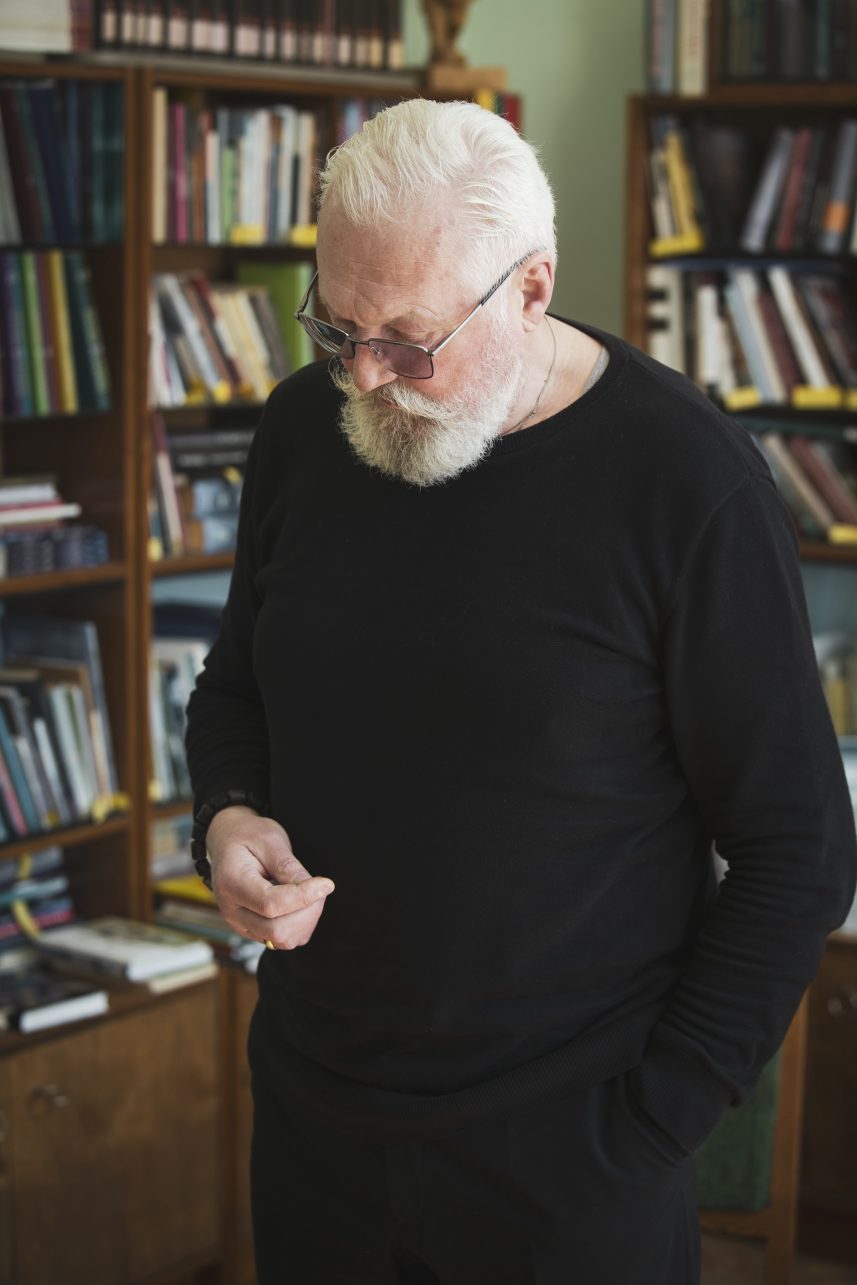

Gediminas Jankus, chairman of the Kaunas branch of the Lithuanian Writers’ Union, has been awarded the 2022 Kaunas Culture Prize for his long-standing, active, and significant cultural work. This award is a great excuse to finally have a coffee together. We did that, as he pointed out, on the historic armchairs of the Kaunas branch of the Lithuanian Writers’ Union, where many well-known Lithuanian writers sat, discussed, wrote, and shared their work. One of them is in front of me. He is not only a writer, but also a journalist, politician, public-spirited person, freedom fighter, and rifleman.

A Kaunasian to the bone

I am greeted in the street by a man of cultured appearance, with a sturdy build uncharacteristic of his age, dressed head to toe in black and sporting a very neat beard and mustache. From the get-go, there is no awkward silence, and we immediately launch into a discussion.

G. Jankus certainly has a lot to say. Kaunas has been his home since he was a little boy. Like many Lithuanians, his family roots lie in the countryside, but the current head of the Kaunas branch of the Lithuanian Writers’ Union grew up and created where two of Lithuania’s largest rivers meet.

“I lived in the Old Town and went to the Komsomol secondary school. Now, when I am invited to the anniversaries of Aušra Gymnasium, I always remind them that I didn’t study there. After the war, Aušra was destroyed. You cannot escape history. At that time, it was a Komsomol secondary school, an ideological forge. With all due respect, I can say good things only about several teachers, and I’d rather forget about the rest. There was a lot of square-bashing,” the writer says.

According to him, there was tension in the educational institution. At the Soviet school, he and a couple of friends used to play pranks by drawing the Columns of Gediminas, even though the headmaster would threaten them with a policeman’s baton. However, the trust between the friends never wavered.

Passionate music lover and collector

A collector can be added to many different epithets that my interviewee holds. Gediminas Jankus is widely known as one of the few people in Lithuania who actively collects old shellac records, gramophones and turntables.

“No matter what it was called in the Soviet era, in our family the current Kaunas State Musical Theater was always called by its original name – State Theater. Even as a child, I fell in love with opera and classics, and I still remember seeing the greats of the stage live. The love for music that was instilled from a young age caught up much later and became a passion for collecting,” Gediminas says.

It all started with a German cabinet with an integrated gramophone bought unexpectedly in Utena a couple of decades ago. Here, the author unexpectedly found a catalog with 100 shellac classical music records. Now his collection contains about 3 thousand releases from all over the world. He had to look for Lithuanian vinyl abroad and they were shipped to him from expatriates living in Australia and the USA.

The writer believes that he inherited his love for culture, the written word, and Lithuania from his parents, especially from his mother. She was, according to him, truly opinionated. She did not mince her words and was always direct when speaking to the bureaucrats. There were troubles, but the family persevered.

Vytis hung on the wall even during the Soviet period

Gediminas Jankus’ parents avoided exile to Siberia. However, other relatives were affected, especially the uncle. As he himself says, for some minute things, which he does not comprehend to this day. The uncle died without understanding why he was exiled.

“It so happened that my mother ended up in Estonia, where she graduated from Tartu University and until 1940 worked as a secretary at the Lithuanian embassy. I remember her story: Bronius Dailidė told her that in a month they will all return to work. Unfortunately, that did not come to pass. The occupation was prolonged,” the writer explains.

Her literary activity began there, she translated Estonian poets into Lithuanian literally, and local poets, such as Liudas Gira, adapted them to proper Lithuanian. My mother spoke English, German, Estonian and other languages fluently, and for some time she worked at the state radio station.

His father was neither a diplomat nor a political figure. He dedicated his life to sports. Petras Jankus was a track and field coach and a referee. G. Jankus claims that even during the Soviet era, his father’s office wall was decorated with Vytis, a medal for independence struggles, and a photograph in which A. Smetona hands him a flag during the national Olympics. In addition, a little-known fact: Petras Jankus is immortalized in a sculpture of a sitting man in Ąžuolynas, in the territory of the former conservatory, near Vydūnas Avenue.

40 years in the field of culture

Gediminas Jankus started engaging in cultural activities in 1983. Back then he visited the Kaunas branch of the Lithuanian Writers’ Union and got a job at the drama theatre together with Jonas Vaitkus. He later followed the director to the National Drama Theatre in Vilnius, where he continued his work until the beginning of the independence events.

He says that in this office, where we are sitting now, he started writing his first play 40 years ago. “I have been very interested in Vydūnas since I was a child, I still have the original editions of his work that I bought in my youth. My play – in the form of a manuscript – started circulating in 1983; it was also published. But it was still a bit too early then, the reform was still further away, so we staged it with Jonas Ivanauskas only in 1988, on Vydūnas’ 120th birthday.”

Dramas about Lithuanian historical figures are the author’s shtick. He says that strangely they were approved even in the Soviet period. Seems like Lithuanianness was still quietly smoldering in the blood of some apparatchiks.

“Surely, I used to think, I won’t pass the censorship. You complete a play and then you have to take it to the board of artistic affairs, where it goes through a kind of censorship.

There was this head of the board of artistic affairs named Julius Lozoraitis. I bring him a play about V. Kudirka that contains many Russianisms, and mockery, and I also write about Trotsky in there. But he approved all my historical plays. It was surprising then and still is now,” the playwright says.

20 years of public service

Gediminas Jankus was a member of the Kaunas City Council from 1997 to 2003, Vice Mayor and First Deputy Mayor of Kaunas from 2000 to 2003, and Director of the Social Affairs Department of the Municipal Administration from 2003 to 2011.

He also actively contributed to the establishment of the national defense structures of independent Lithuania and became the first head of the restored Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union.

“I have dedicated a large part of my life to the city I love and to solving social problems. It’s a pity, but times were tough. There were many disappointments, the city didn’t have money for everything, but we did our best. I fought hard for the people, I tried to make decisions that would be useful in reducing the exclusion created by bureaucracy,” G. Jankus recalls his work.

However, one of the most notable stages of his career was his position as the first Chairman of the Riflemen’s Union after the restoration of Lithuania’s independence. Gediminas Jankus actively contributed to the restoration of this organization since 1988. “I heard by word of mouth that the Riflemen’s Union was going to be re-established. I thought to myself that it was wonderful news, after all my father was also a rifleman. The first people to support it were the Union of Political Prisoners and Exiles and Audrius Butkevičius. We were acquaintances, so I didn’t hesitate for long, and I joined it,” G. Jankus recalls.

Not afraid to die

“Even before the January events, there was a long prelude, which I cannot forget, and which pushed me into a combative phase of my life. Our people were being beaten at the border, the trailers were being set on fire and the tragedy of Medininkai took place. Back then I published a long article saying that the path of compromise is the greatest betrayal. Kauno diena risked it and published it.

The writer says he was sick of the empty declarations when Lithuanian citizens were terrorized. Little by little, he put aside all his creative activities and devoted himself to the Riflemen’s Union. In the statutes, which were approved by the Vagnorius government, he wrote that he would defend Lithuania’s independence, and if necessary, with arms.

When the new year of 1991 arrived, it was already clear that an attack was not only predictable but also expected. Gediminas Jankus took the oath of office and took command of the rifle squad that defended the parliament building.

“We waited and had prepared to die. We knew the enemy was stronger, but we were not going to give up. There were many misunderstandings, including an order to retreat for the armed guards, but we stayed because we could see the chaos unfolding around us,” the freedom fighter recalled.