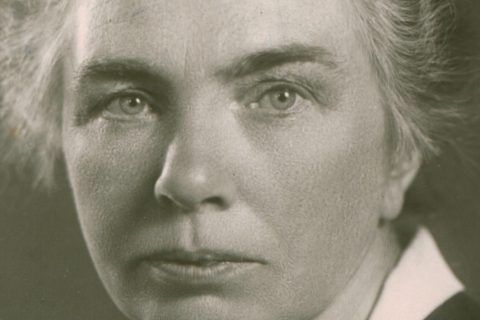

Lithuanian Women’s Movement: The End of the 19th Century – The First Half of the 20th Century, this is how Virginija Jurėnienė named her doctoral dissertation, which she defended in 2004 at Vilnius University’s Kaunas Faculty of Humanities (now Kaunas Faculty). She still works there today and is one of the creators of the master’s study program in art management, and is a teacher loved by students.

When inviting the scholar for a chat for the Female Gaze issue of Kaunas Full of Culture, I sort of wanted to talk about women in the interwar period government. But the professor is already preparing her seventh monograph, so we decided to discuss its context instead. And here things get even more interesting. Although, of course, there is still room to talk about Gabrielė Petkevičaitė-Bitė, who wanted to become the first female president in the world, or a book smuggler and parliamentarian Felicija Bortkevičienė. By the way, 2023 has just been declared the year of F. Bortkevičienė. But now let’s travel to the 1990s.

Virginija, you are preparing a monograph on women in the Reconstituent Seimas. Why did you choose this topic?

Until last year, I was immersed in the stories of very active, goal-seeking women who saw what was needed. I am talking about women politicians of the interwar period. Now, with my colleague Giedrė Purvaneckienė, we are carrying out a project of the Research Council of Lithuania. We are investigating how our society has changed since 1990. Prehistory was needed, so we looked at 1988 and I, personally, also checked 1987. We were looking for roots. Why only twelve women were elected to the Supreme Council in 1990 among 141 members? Two more joined later. It is very strange, because in the interwar period, when education was less available for women, and they had just left the home space, there were as many as eight of them during the entire Constituent Seimas.

Later, 50 years of occupation followed. During that time, more than half of the female population graduated from universities or vocational schools. Emancipation took place, although it may have been forced and gender equality was declarative. However, the society was educating itself, becoming more modern. Women worked, occupied managerial positions. So, what happened that during the restoration of independence they backed away? I did a lot of interviews, researched sources, I really wanted to answer this question. It was a big blow to me as a historian. I was convinced that in the Soviet era, women’s social consciousness existed. Turns out I was wrong. When the occupiers came, they closed the women’s organizations that operated in the interwar period. The model of the Soviet Union was used, and a new republican women’s council under the union was established. Each district and even the labour collective had its own women’s councils. Although they were led by competent specialists, they did not perform the function that the organizations performed in the interwar period, when women in organizations educated themselves and educated others on various important topics. Women founded and maintained the first kindergartens. And in 1990, the Restorative Seimas expressed a desire to close kindergartens!

Why?

For the mother to return to the family. It’s like we wanted to go back to the First Republic, but we went back even further. Other societies reviewed their history, rejected what was inappropriate, reorganized, and adopted new strategies. I agree that the mother is important for the state, otherwise the state will not exist. But as a scientist, I think that this is a negotiated path. You have to negotiate with a young family, a young woman, offer her something, not just order her to return home. I looked through all the press of that time, as well as the records of rallies. As I wrote in my monograph, there wasn’t a single meeting that would loudly say that a woman needs to preserve her workplace, that we need to create conditions that would allow her to have a family and also maintain a place in society. I think we simply didn’t see other options on the euphoric path to freedom and we are paying for those mistakes now. Although “we are paying” might be too bold a word. But there is a conversation now that the mother should return back to work earlier, and a father should take a paternity leave. And they do that. I think we raised great sons who are not afraid of responsibility. But it was necessary to consider back then. A study carried out by the Department of Statistics in 1990 states that only a little more than a quarter of all 1,390 women surveyed wanted to “return home”, all others wanted to work, lead, live. And yet, the minority won.

Here I invite you to go back to 1987, when the women’s council, wanting to strengthen its position, proposed extending paid maternal leave. The authorities of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic approved that a mother could raise a child up to 1.5 years. During the Reform Movement, people were talking about 12 years! Many things were sought back then that still haven’t been implemented. The provisional basic law that was adopted on March 11, 1990 (it performed the function of constitution, ed. note) tried to equate the domestic labour of women who have more than one child with the work in the state. Home economics. But here, we turn to the constitution of 1922. The women who were in the parliament then, agreed that the family is the basis of the state, but they asked to equate raising children with any work outside the family. Women in the US were vocal about it in the 1960s. Then it was calculated that if you add up all the work that mothers do at home in a year, that is, laundry, cooking, cleaning, it would be the budget of one year in the United States. And Lithuanians are even more hardworking. But who forces them? When you’re dating, things are equal and when you get married, all jobs fall on the woman’s shoulders. Maybe it has something to do with women’s education.

I wonder if a woman ever managed to move further away from the family.

Unfortunately, no. During the occupation, women were very tired of all that domestic labour and working outside the family. So, yes, maybe they imagined that they would be happier when they returned home. But that did not happen, because the woman’s financial independence disappeared. After all, we are talking about a period of transformation, a liberal market, privatization. The easiest part of managing that chaos was to get the woman out of it. But doesn’t it remind you of the Great Depression of 1929-1933, the global economic crisis? Back then, states also needed happy children and the women who raised them at home. However, the birth rate in Lithuania fell. In 1992 we woke up, the bubble burst. A boom in non-governmental women’s organizations began. The collapse of kindergarten infrastructure has been stopped. And once again, education became the most important thing. How to return to the labour market, how to introduce yourself to an innovative employer? When and how to say that you have a doctoral degree and would like a relevant position? When at that time, after raising two children, I wanted to go back to university, it was very difficult. But I always knew what I wanted, and I didn’t agree to the terms. A new condition was set for me: a return exam. I went to the vice-rector and – I bow my head to him – he agreed that the job position was guaranteed to me by the diploma I had and the laws. So, the state’s desire to exalt the mother was very noble, but in reality, no one took her into account.

Perhaps this is kind of a short answer to a question why there were so few women in the Reconstituent Seimas.

There were even less of them after the elections of 1992: only ten. One of the most striking examples of how a woman was pressured and even despised is Danutė Kazimira Prunskienė. A charismatic, intelligent, influential scientist and economist recognized in Western Europe joined the Reform Movement. She revealed in her memoirs how her leadership ambitions were stifled, even after becoming prime minister. “Oh, this was said by a woman,” the politician would receive similar disparaging remarks. I discovered an interesting thing last night. I was reading Politician’s Notes where she claims that there should have been another woman in the Government of 1990, also very capable and talented, but the powerful men did not let her pass. Women were considered by many to be mainly helpers. This came from the Soviet era, when women were men’s deputies.

Very often, in critical periods, women become responsible for the state

In my understanding, those 14 women in the Seimas of 1990 show a very polarized society. A collapsing system against a new system: there was no tolerance. The women who, for example, headed the councils I mentioned (and this was a public position, without additional pay) chose to quietly leave so that no one would attack them. They protected themselves, protected their families, chose a quiet life, although it was not necessarily characteristic of them. The Republican Women’s Council quite quietly transformed into the Lithuanian Women’s Society. Its branches continued to implement the politics of the new Lithuania, only the leaders did not participate in elections, rally organization and everything else. This non-governmental and non-political organization is still active today, doing great work, and is a member of the International Council of Women.

But tell me, how can you voluntarily go into politics when you know what awaits you?

I will quote Danutė Kazimira Prunskienė. She said that she could have obeyed the clan, then she would have become untouchable, but as a person with the competencies she had, she could not do that to herself. Here’s the answer: politics are all about clans. But if we didn’t have any women in politics, it would be very insensitive. Men make money, take risks. And who feeds the family? Mother wolf. Very often, in critical periods, women become responsible for the state. In 2009, during the crisis, who was elected president? Dalia Grybauskaitė. Who became the Prime Minister in 2020? Ingrida Šimonytė. Why? Was there a lack of men in suits? I don’t think so. It is a question of responsibility. How to continue steering the state? Lithuania is not unique here. Except that we are often afraid of a different opinion. And I, living in a democratic society, am not afraid to say that 30 years ago we made mistakes by not looking for compromises.