Many of the buildings on V. Putvinskio Street have a very interesting, multi-layered history. And if there was an election of the most interesting one, the building of Kaunas Artists’ House would definitely take one of the first places. Many are aware of the original unfulfilled purpose of the building – the diplomatic mission of the Holy See was to be located here.

Many people might also know that the designer of this building is Vytautas Landsbergis-Žemkalnis – one of the most prominent architects of that time. As the building completes its renovation and awaits its 50th anniversary, we invite you to remember more of its historical moments.

1930s. Then, the street still known as Kalnų, gradually takes on a prestigious shape. In the very center of the city, but away from the traffic flows, the quiet street becomes an attractive place for prominent public figures to build their houses. At the end of the year, a cornerstone is laid here for one of the most important representative constructions in the country: the building of the national museum complex. The nature of the place also attracts foreign missions: US and Swedish consulates settle next to the already operating French Embassy. Across the street from the future museum site, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is purchasing a small house on the site on which it plans to build a residence for the nunciature of the Holy See. The project of the building is given to Vytautas Landsbergis – a young architect who had already made his mark – and in September a tender for the construction of the building is announced.

Without going too far into the intrigues of international relations, the good relations between the Lithuanian government and the Holy See soon cool down, and in June of 1931, the nuncio leaves Lithuania. The newly built villa does not welcome its visitors. The building soon takes on another important role and radically changes its “profession”. At the turn of the decade, the state did prioritize education and health care, but the hospitals in the temporary capital were in a rather sorry state. The talk about building a new large hospital (future clinics) will only be substantiated a decade later. The “failed” nunciature is handed over to the Ministry of the Interior, which transfers a State Children’s Hospital and Vytautas Magnus University Children’s Clinic here at the end of 1931 (before that they were located on the nearby Maironio Street and operated under unfavorable conditions).

People were happy not only about how comfortable the new building was but also about its “healthier environment”. The building was surrounded by a spacious yard and a part of the Green Hill slope. The soul of the hospital and one of its founders Prof. Vanda Tumėnienė, who has tirelessly fought against children’s diseases, also moved into the new building. It was a big event for the hospital. Later, V. Tumėnienė remembered the building fondly in her memoirs, “It was … a beautiful, fun, sunny villa, nicely furnished inside, with parquet flooring, large windows and balconies leading out to a beautiful garden.”

The largest room in the building, which was once to become the nuncio’s dining room, was dedicated to science – an auditorium was established here. The ground floor was also equipped with a bandage room, probably the most modern X-ray in the city, two wards for older children, an isolation ward, a staff kitchen, a dairy kitchenette and a small dining room. On the second floor, six wards were allocated for babies and young children, and two for mothers with children. There were also small offices for the doctor on duty and for V. Tumėnienė. The hospital was able to treat around 50 children at a time: 20 adults and 30 infants. As there was not enough space for all the needs of the hospital, a wooden house, located next to the street, was rented. It contained an outpatient clinic and two isolation wards in the attic for potentially infectious diseases. There was no ward of infectious diseases for the same reason: there was simply not enough space.

The building is also important because the future pediatricians from all over the country were trained here. In the auditorium prof. Tumėnienė taught a course of pediatric diseases to the 7th and 8th semester medical students. “In the clinic, students improve their skills in pediatrics, study propaedeutics of children’s diseases and undergo patient care training and learn how to write down medical history.” The professor later wrote, “The clinic on Putvinskio Street, has truly flourished, has shown great progress in science, student training and the training of medical professionals.”

The auditorium of the white villa has seen many visiting professionals. The famous French physician (true, later he became known in a much more unfortunate context), Paul-Félix Armand-Delille had briefly described his visit in 1934, “There is a children’s hospital in a beautiful pavilion, where Prof. Tumėnienė teaches. In it, I saw a room specifically designated for the treatment of cerebrospinal meningitis because there was a small epidemic there at the time. … I demonstrated an intracranial lipiodol injection, which was not yet known there, in the auditorium of this clinic.”

In 1940, after many years of discussions, disagreements and problems, perhaps the largest project in Kaunas at the time – Vytautas Magnus University Clinics – was being completed. The pediatric clinic also moved to the premises equipped according to the latest requirements and V. Tumėnienė’s recommendations. It might have been a coincidence but in the last years of independence, the relations with the Holy See have returned to normal and the villa would have finally been used for its original purpose, but the fateful summer of the same year took away this need. At the beginning of the occupation, the diplomatic representative left Lithuania, and the building was destined to accommodate the sick a bit longer. At that time, it experiences another subtle touch of history, as evidenced by the surviving photographs. In a villa decorated with propaganda slogans, the elections for the so-called People’s Seimas were held.

The central dispensary for the prevention and treatment of tuberculosis was solemnly opened in the building at the end of the summer and the same slogans and propaganda canons permeated the ceremony. The press, which was already serving the new ideological needs, described the premises with a fervour characteristic of the time, “The hall … was decorated with red flags and portraits of Lenin, Stalin, Paleckis and others. There was a slogan between the red flags, “The socialist system will defeat tuberculosis, the enemy of working people.” In addition to the new or lost functionaries, the celebrations were attended by medical staff, who found themselves in a strange situation, including former President of the Independent State Kazys Grinius, who had left an important mark in the fight against tuberculosis earlier. Needless to say, the developments and achievements in the fight against this disease that happened in the 20s and 30s were not mentioned here. The dispensary was equipped with two examination rooms and twelve beds, and a children’s dispensary was located in the adjacent wooden building. At the end of the war, other premises were found for the dispensary, and a sanatorium-type nursery was established in the villa. A little later, after the 1940s, the former second-floor terraces were glazed and converted into rooms.

In 1971, during the years of occupation, with a wide variety of systemic creative unions and associations, the executive committee of Kaunas city assigned the building not only for the administrative needs of its culture department, but also to the Palace of Creative Intelligentsia, which were later renamed as Kaunas Artists’ House. An adaptation project was prepared at Komprojektas.

It is interesting that the architect S. Steponkus, who was responsible for the architectural part, tried to restore the exterior of the building to the original image, at least in part. The covered terraces, after removing the windows were supposed to become open again, “just like the building’s architect originally intended.” After the reconstruction, a little roof remained in the large terrace and the space that appeared in the place of the small terrace is still there today. The building was then expanded from the more neutral side of the yard. A second outhouse was built above the one-story one.

The four large ground-floor rooms, which were once to become nuncio’s study, salon, dining room (now a VMU auditorium) and conservatory, which were separated by a sliding door, became a single hall with a stage after the reconstruction. There was a plan to establish a cafe next to it, “with the following menu: coffee, cold snacks, sweets, cocktails, alcoholic beverages.” The furniture for the official premises on the ground floor, had to be made according to individual projects. In the living room and cafe, they had to be made of oak plywood, emphasizing light color, as if trying to adapt to the old modernist spirit of the building. A true novelty was planned for the event hall: suspended calcium silicate boards, modern lighting fixtures and new doors as well as radiator fittings that were supposed to me made of ash plywood. Parquet flooring was not changed, only restored. On the second floor, the offices of the head of the Culture Department, his deputy and secretary were installed along with the Art Workers’ House directors, inspectors and methodologists’ offices, accounting and library. The building opened its doors to new residents and guests in September 1972.

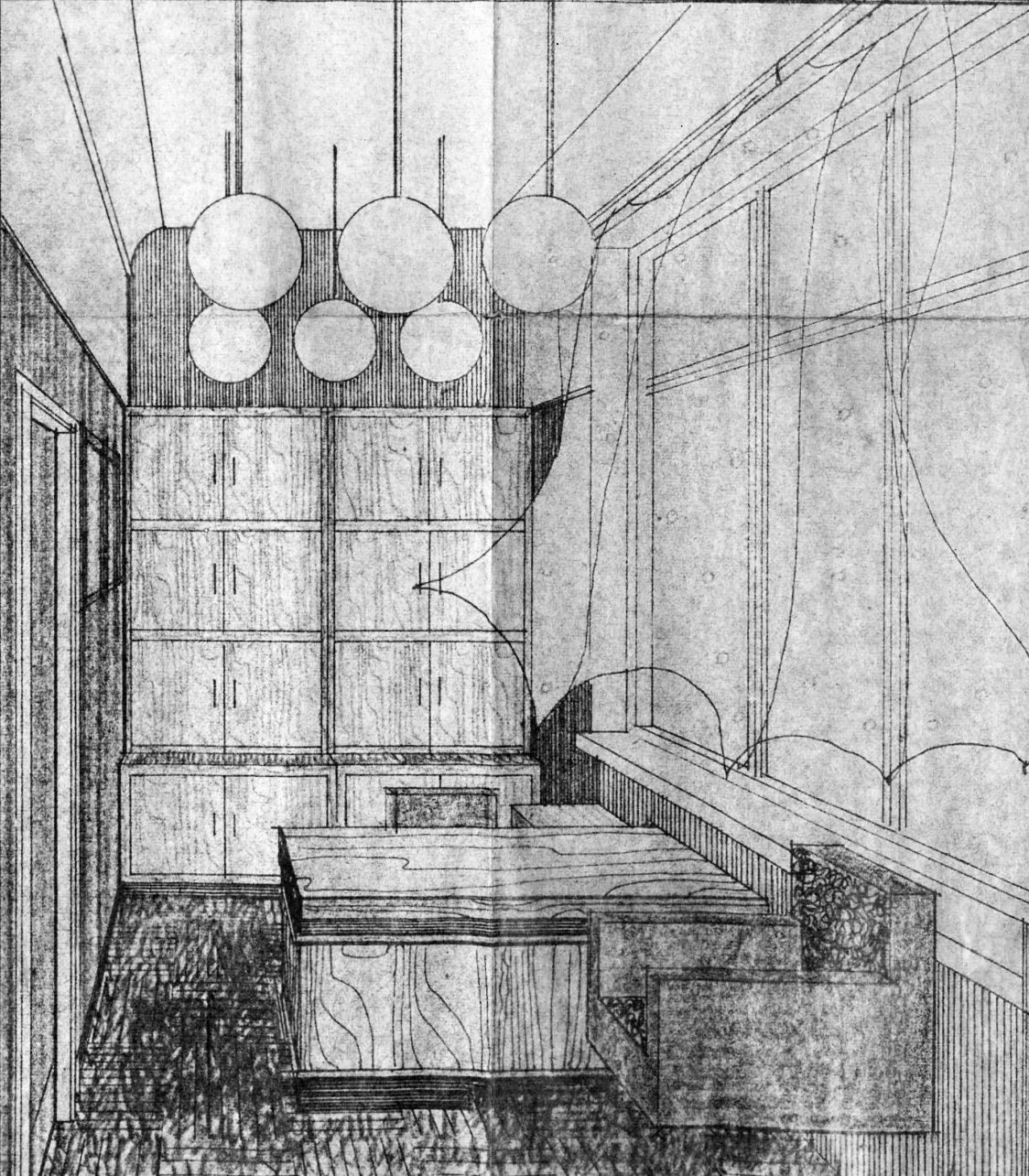

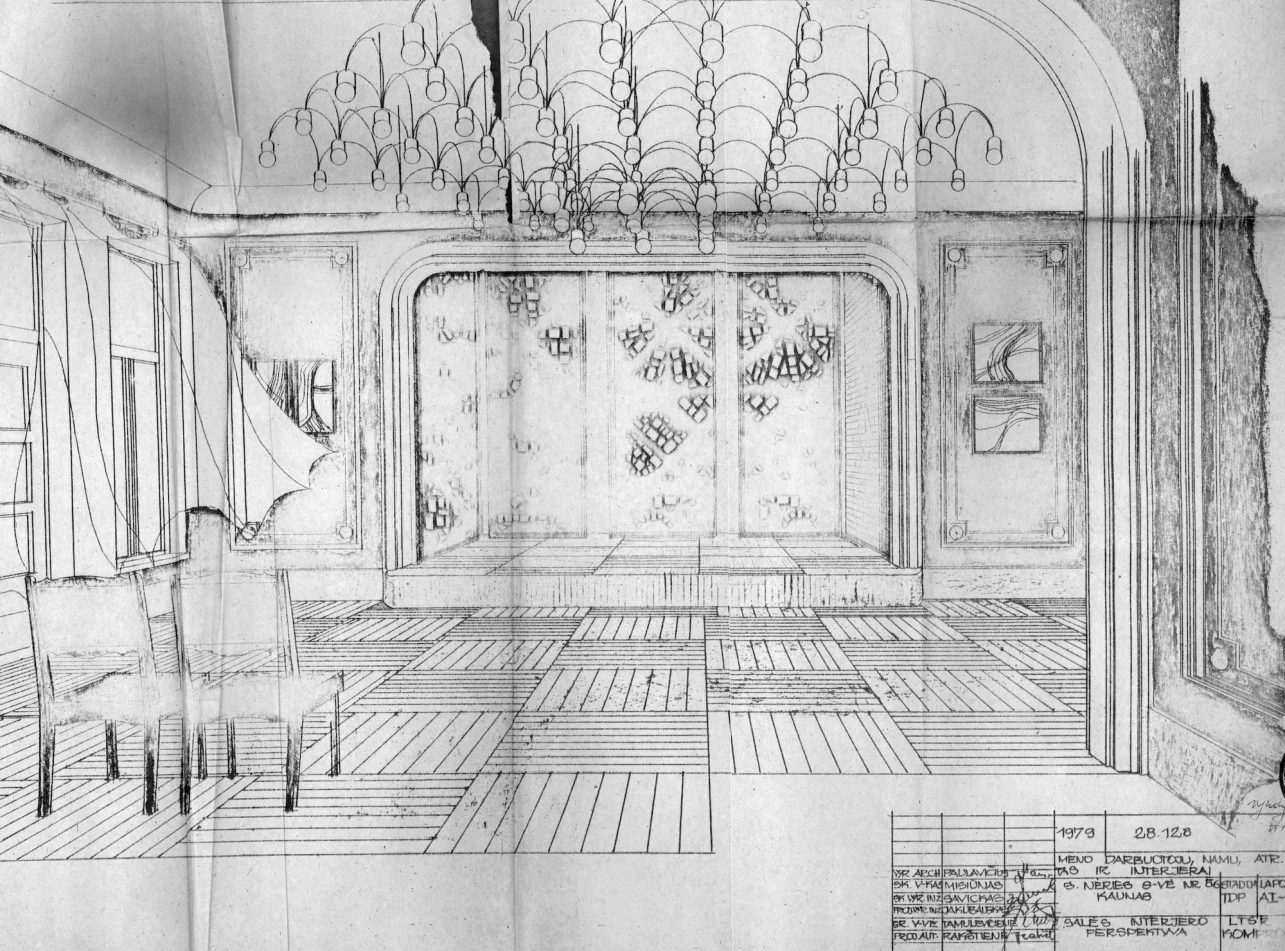

After less than a decade, the doors were closed again for major reconstruction. In 1979–1981 several reconstruction projects were prepared by Komprojektas architects Jakubauskas, Tamulevičienė, Rakštienė, Žibas, Savickas and others. After the reconstructions that took several years, Kaunas Artists’ House opened up on 1982 – its tenth anniversary – having changed considerably. In addition to the major exterior repairs, the layout of some of the rooms has been redesigned, and the representative spaces were decorated with new artworks. A panel created by ceramicist Aldona Keturakienė appeared in the lobby. Vytautas Banys’ Muses settled at the back of the stage in the windows that were supposed to illuminate the winter garden and the cafe was decorated with Valerija Ostrauskienė’s creations. The walls and ceiling of the hall were decorated with gypsum moldings. It was decided to use hardwood and walnut plywood for the wall panels, radiator cladding and stage decoration in the main spaces. Early reconstruction suggestions prepared in 1979 contained the idea of re-bricking the terrace above the main entrance and installing big round windows there. Despite the appearance of new space, the idea of facade diversification was not implemented.

Until the restoration of independence, no major renovations took place in the building. Leaving the recent history of the building and the transformations and returns that take place today to future historians, it is worth mentioning that although there were attempts to use the building for different purposes in the early 1990s, the villa has remained a home for artists to this day.