Both cities and the lives of their citizens can be colourful. The story of Regina Žukauskienė is colourful not only because she devoted part of her career to studying the shades and tones of facades. She is an architect, politician, public activist, active member of different communities, animal lover, furniture designer, and most importantly for us, polychrome researcher and specialist with more than 40 years of experience in the most famous buildings of Kaunas and the whole of Lithuania.

There were some dark colours, too

The beginning of Regina;s life would fit into the monochrome palette of Siberia. Like more than one special person interviewed for this magazine, she was born in a family of deportees in the Irkutsk region, Usolsky district, near Lake Baikal. “My father was sentenced to 25 years in prison. He worked in the mines in Magadan for the longest time. He suffered an injury there; his leg was crushed. After Stalin’s death, he was tried again and allowed to return, although he was never acquitted. Allegedly, a traitor to the homeland, the organizer of the coup,” the architect says.

She didn’t really plan to study architecture or work with heritage when she returned. Her passions were history and journalism. However, life led her to Vilnius Construction Technical College, after which she was immediately appointed to the Institute of Monument Conservation. “I learned a lot because at that time it was one of the strongest institutions in that field in the entire USSR. I was a good student and did all my internships at the Institute of Monument Conservation. My thesis supervisor Alina Samukienė was from it, so I also started working there afterward; it was an extremely good environment,” R. Žukauskienė says.

The interviewee’s first job was at the church of St. Francis of Assisi (Bernardine) in Vilnius, she was working on its stairs. Then followed the St. Archangel Raphael monastery where she had to design window grills. Then the preparation of Trakai wooden architecture records, measurements, and polychrome studies. That’s how a 42-year-long career began.

Her biography contains the most famous objects of Kaunas After a couple of years of working in the capital, Regina Žukauskienė became a love emigrant and came to Kaunas. Since she was a good worker, it did not take her long to find a job. She was transferred to the Kaunas Department of the Institute of Monument Conservation, which was located on Raguvos Street at the time. “My first jobs in Kaunas were the State Musical Theater and the so-called 13-14-15 quarters, where Vytautas Magnus University and Vilnius Academy of Arts Kaunas Faculty is located now on Muitinės Street. I also managed to work with all the greats on the restoration project of the old town. The fact that there were workshops of manufacturers and restorers near the institute also helped to accumulate a lot of experience at the time. We were able to discuss everything immediately, look for solutions, share experiences,” Regina recalls.

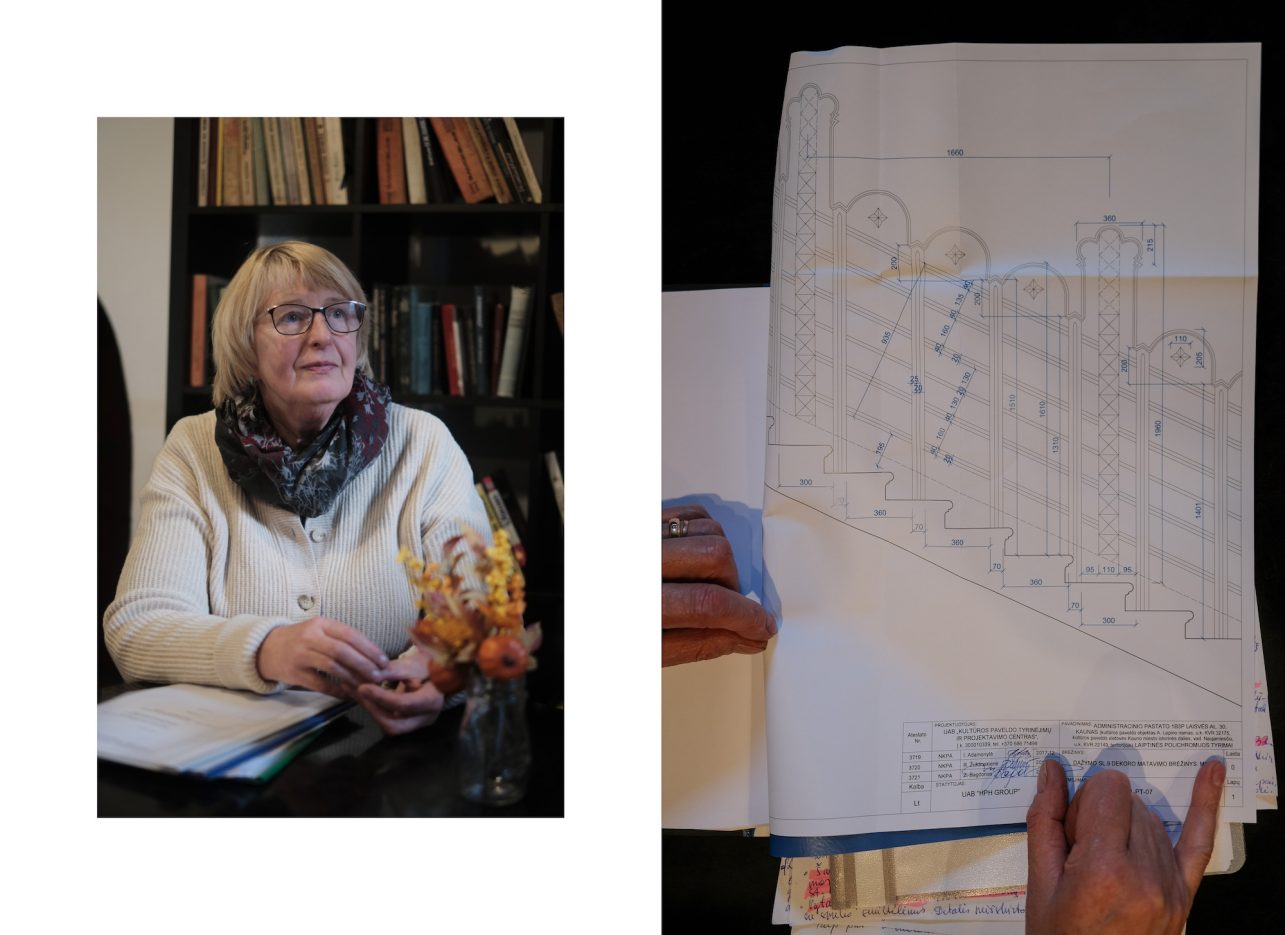

The interviewer emphasizes that a particularly important professional friendship was established there. She started at the institute with her colleague, architect Indra Adamonyte, and they worked, consulted, discussed, and sought solutions in Kaunas for almost 40 years. The professional archive takes up a lot of space in Regina’s house. It is full of manuscripts, research reports, and programs as well as projects carried out over several decades. Among them, are Lapinas’ house on Nepriklausomybės Square, the former Vilnius bank on Maironio Street, and many others.

The researcher singles out the Kaunas Fortress commandant’s house where the Lithuanian Armed Forces administration is currently located, as her most memorable work. “I won’t be lying when I say that we worked on one object for 25 years. We researched everything from facades to interior decor, windows, floors, and doors. We found a lot of authenticity that we didn’t expect to find, even details reminiscent of Art Nouveau style. The study of polychrome is a difficult, long and painstaking work that not everyone can do.”

So, what is polychrome?

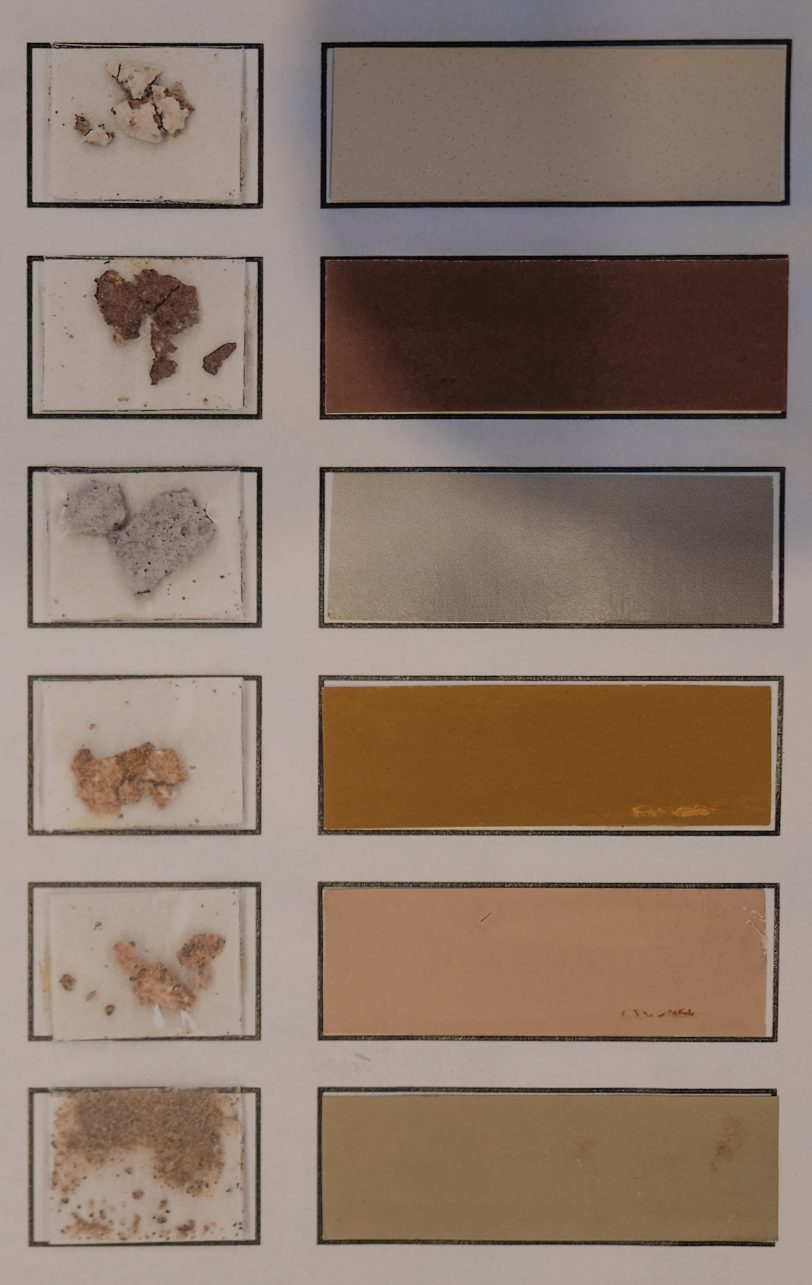

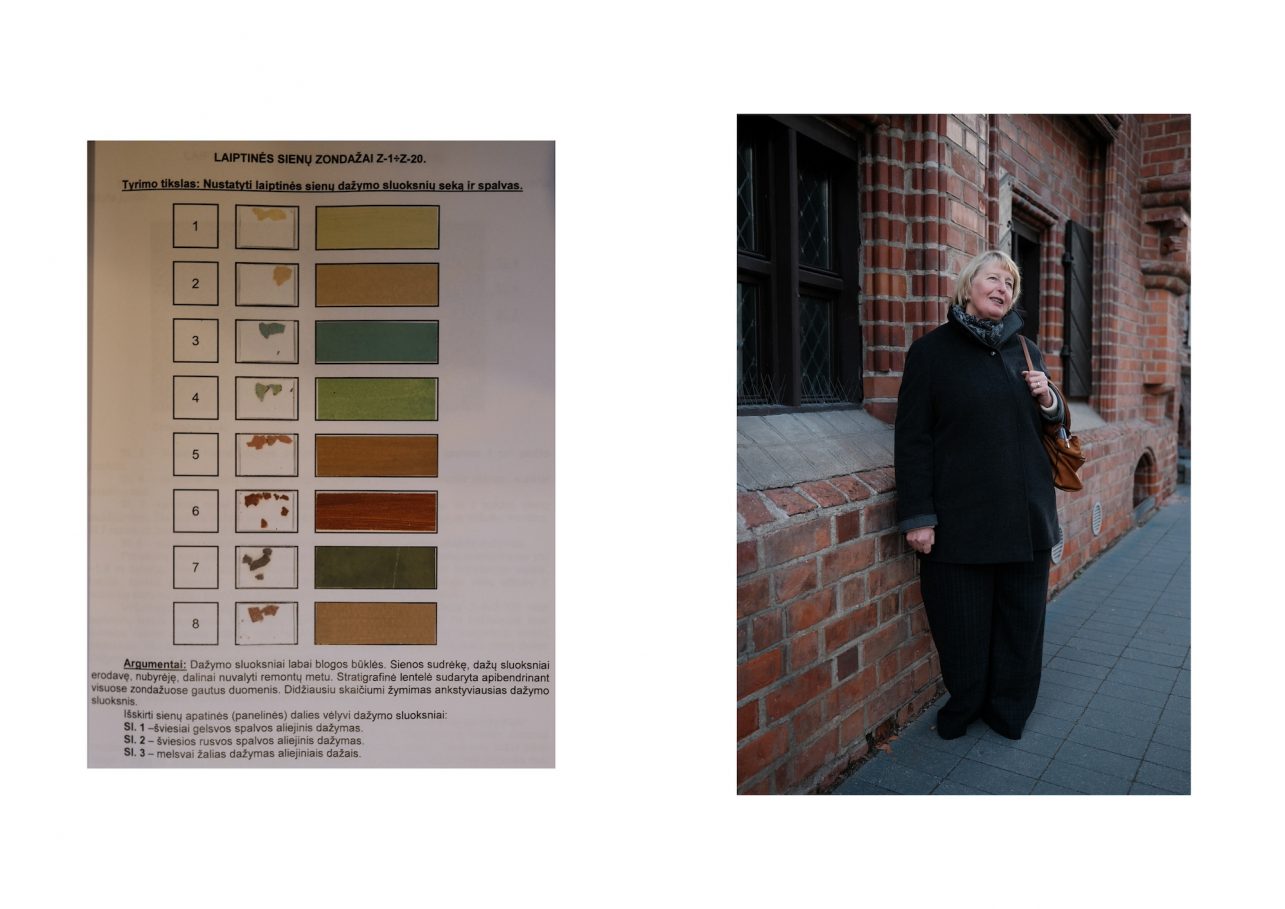

In short, polychrome means multicolouredness in Greek. “One of the management’s types is research. It can be architectural, artistic, historical, and also polychrome. The latter are related to colours, decoration, and painting, including buildings, individual elements, details, and scenic painting, which can be found in both interior and exterior. Our goal is to discover primary, original colours and offer combinations that best match them,” the specialist explains.

My interviewee is principled. She says that you must come to the object and leave after completing the work without having left any trace, you don’t exist as an author. It is necessary to understand the context, consider the authenticity, and delve deeper. You are not doing what is beautiful to you or what you want but what is necessary to restore that building as a whole. In her opinion, all small invasive changes usually bring destruction. It takes professional talent to control the whole.

Before starting work, you should always read everything you can find about the object. Historical research, archival material, previous work of colleagues. When you’re looking for something hidden, every detail can help.

“You develop that sense not after a few years, but after a few decades. Only then do you know what and where you will find; maybe under the windowsill, in the inner corner of the ledge, or perhaps under the balcony, where it doesn’t rain. This requires many years of experience in architectural research,” R. Žukauskienė continues.

Does not work in laboratories

I’ve always thought that this research is done in laboratories. The samples are collected, and researchers in white coats put the samples in special devices, finally, a piece of paper comes out that answers all the questions. Unfortunately, I was wrong.

“We often investigate old, abandoned buildings, and we spend months in the cold and damp, next to mold. We often work at great heights, on scaffolding. Sometimes it is very difficult to acquire samples, so you spend hours with a medical scalpel with your hands raised at the church vault outside,” the longtime polychrome expert says.

Polychrome research often helps to determine the evolution of changes in a building. For example, you can find only 2 – 3 layers on a reconstructed building, but there are also such objects where you find dozens of layers and dozens of different colours. In this case, it is usually not the laboratory that will help to determine the primary colours, but diligence, knowledge of painting techniques and the ability to separate paint layers.

Each layer of the examined area should be removed separately, with a medical scalpel. The observant eye of the polychrome researcher not only distinguishes what paint was used but can also connect the changes to historical events, for example, if a thinning layer of soot is found between the layers of paint.

“We take samples on-site, on scaffolding, in the cold. We even explored two forts in Kaunas in winter. You go to work with woolen socks and some strange men’s shoes, wearing three sweaters and an unexplainable work jacket and a cap. You must be a curious person.”

Unfortunately, even professional researchers and experts cannot always tell how one or the other building looked, what the colour of its facade and details were, or what was the interior colour range and decor elements.

“Most of such objects are here in the old town. The more owners, the less likely we are to find something. Everyone wants to repair, rearrange, and change the original appearance, sometimes radically. Humidity and salts also have a negative impact,” Regina says.

The urban palette is constantly changing

While preparing for this month’s topic and looking for polychrome specialists, I heard many times that it is extremely difficult to accurately determine the colour development of a city. This would require extensive academic analysis, and long work with many research reports. This is confirmed by my interlocutor, but we are still trying to determine at least an approximate colour development of Kaunas. “For a long time, there were few brick buildings in Kaunas, wooden construction prevailed, but perhaps the most original image is what we have in the old town – red brick masonry. We can probably consider this colour as the traditional colour of this city, preserved in some of the buildings of the Kaunas fortress,” Regina Žukauskienė claims.

In the past, everything depended on what materials were available. Abroad, we can often see darker shades, where stoneware has been used more. Or, on the contrary, lighter ones where more dolomite rocks are found. We had and still have a lot of clay in Lithuania, so it is not surprising that we are used to red brick walls and tiled roofs.

During the interwar period, almost all facades were painted in one colour, without highlighting the details.

Later plastering on masonry appeared. Neoclassicism and historicism came to Lithuania from Moscow and St. Petersburg along with tsarist occupation, Russification, architects, and other masters. Facades then were decorated not only with colours but also with cornices, pilasters, and capitals.

“During the governorate period, the colour range of the city also begins to change – various yellow tones are especially prominent, they were the dominant ones. Various shades of yellow, brown, yellowish-brown, or gray. It was simple lime paint, which provides a thin coverage, the pigment mixes easily. Apparently, such materials for painting were the easiest to obtain in our region at that time,” the specialist says.

In the interwar period, the number of colours increased but the palette remained similar. “Earth tones were the dominant ones: brownish, yellowish, many light grays, dark grays, cherry or clay red. We also found several objects with a dark green facade, reminiscent of the Soviet military uniform. Very rarely were the details of the building highlighted (something that we like now). During the interwar period, almost all facades were painted in one colour, without highlighting the details.”

And during the years of the Soviet occupation, the city brightened up. Intense colour facades with highlighted, contrasting details, such as ochre, red, orange, blue, black-blue colour planes, and white details are increasingly common. Only that type of paint faded very quickly due to poor quality and the buildings looked washed out.

“But not necessarily. One of the most interesting objects of the Soviet period, on which I worked, is the student campus of the former Kaunas Polytechnic Institute, now KTU, designed by architect Vytautas Jurgis Dičius. Of all the Soviet architecture that I studied it left the greatest impression on me. Although there are only two colours there, black and white, the polychrome research processes were very complicated,” Regina Žukauskienė concludes the interview.