This week’s “Museum Wednesday” is hosted by the Kaunas Ninth Fort Museum. Museologist Valė Gutauskaitė invites you to explore one of the most famous symbols representing our country – the Monument Of Kaunas Ninth Fort.

Marks of time

The threat of large-scale war in Europe in the 1870s forced Russia to strengthen its defence of the western frontiers it had seized. In 1882, the construction of a fortress began in Kaunas. In 1903, the construction of the Ninth Fort, which had to protect Linkuva Heights, began near Kumpė Village and continued until 1913. When Lithuania became an independent state, a division of Kaunas hard labour prison was established here in 1924.

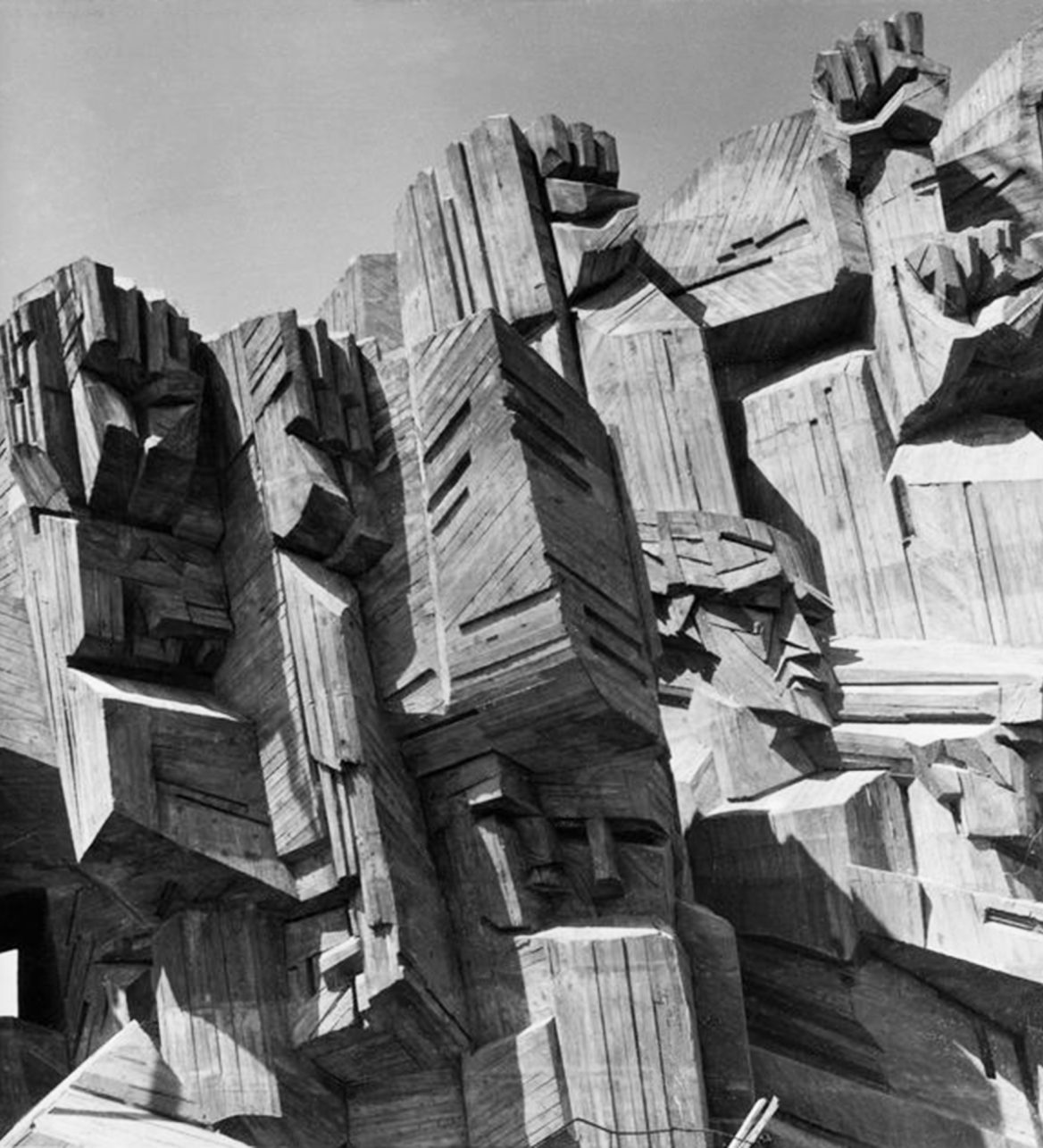

During the occupation of Nazi Germany, the Ninth Fort became a systematic place of torture and extermination, an international “death factory” and a black spot marked by blood. Among the dead were citizens of Lithuania, France, Germany and Austria, who were shot, burned and buried alive. The ground here was soaked in the martyrs’ blood. The flow of time could not erase the tragic events that took place here during the Soviet and Nazi occupations from people’s memory. At the mass murder site, on a hill visible from afar, next to the main Lithuanian highway Vilnius-Klaipėda, a magnificent monument created by sculptor Alfonsas Vincentas Ambraziūnas was erected: a composition of three sculptures symbolising the spiritual strength of a man and his dramatic resistance to cruelty and oppression. One can see vivid silhouettes of people’s faces in the concrete of the monument, and the hands raised upwards with clenched fists send a message to every visitor to this place: people, do not let the tragedy of war be repeated and do not let a new world war to break out, a fire that destroys everything. We are all responsible for peace, security and a stable future.

Memorial

The process of designing and building the memorial complex always was at the centre of attention of the Soviet party and cultural nomenclature. The communist ideology was based on a value system that was supposed to cultivate a new personality type, the builder of communism. The communist government pursued its goal by using artists and the representatives of culture and education. Artists were constantly monitored by the Soviet secret services to ensure that their work adhered to the postulates of communist ideology. There was only one possible direction in art – socialist realism, which was characterised by politicised militancy, dogmatic statements, the principles of folk character and the party. For sculptors, it was extremely difficult to create and at the same time to follow these principles as it was difficult to choose the means of expression and to develop concepts of works that corresponded to the principle of representation “as in life” (socialist realism).

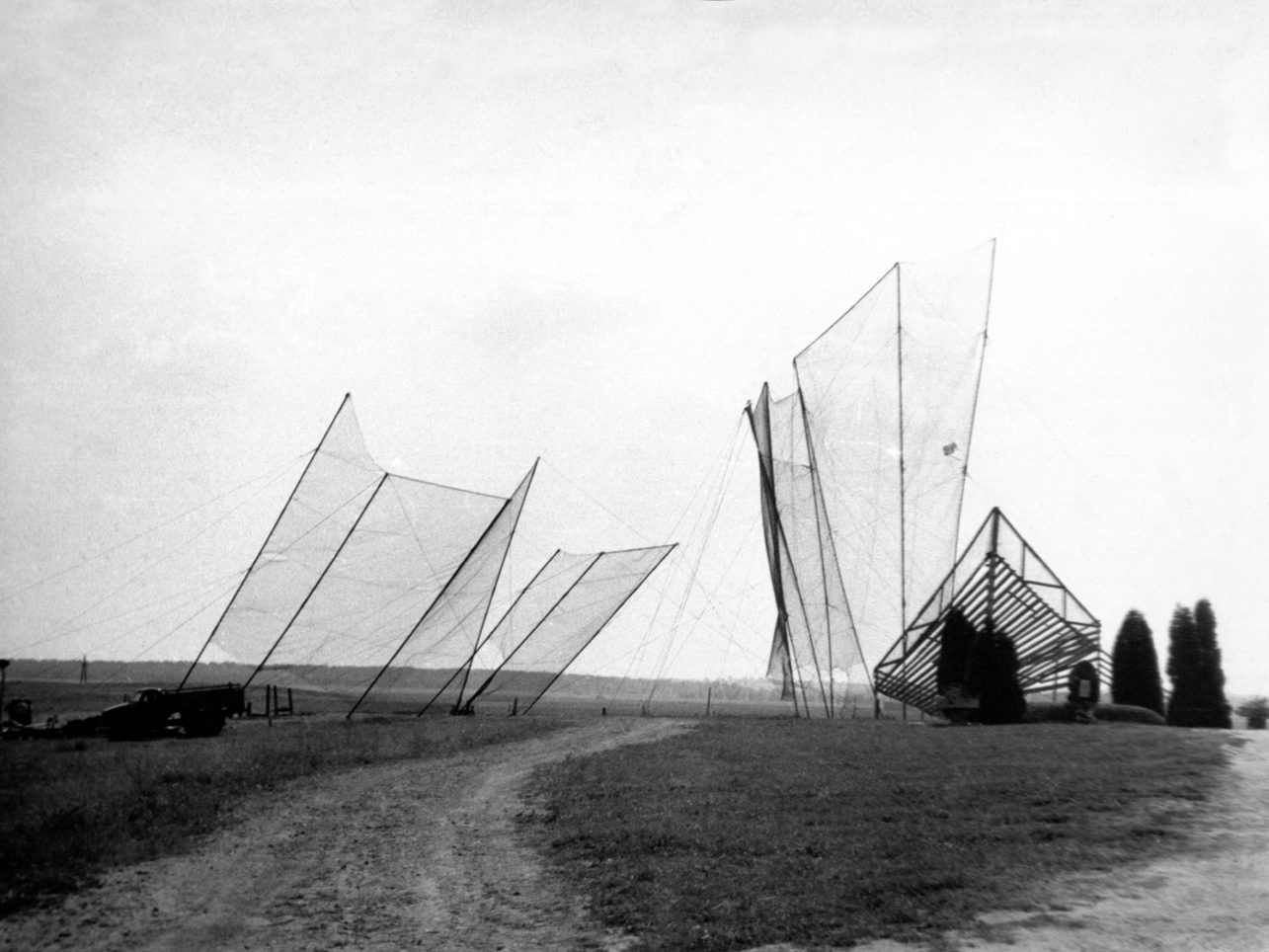

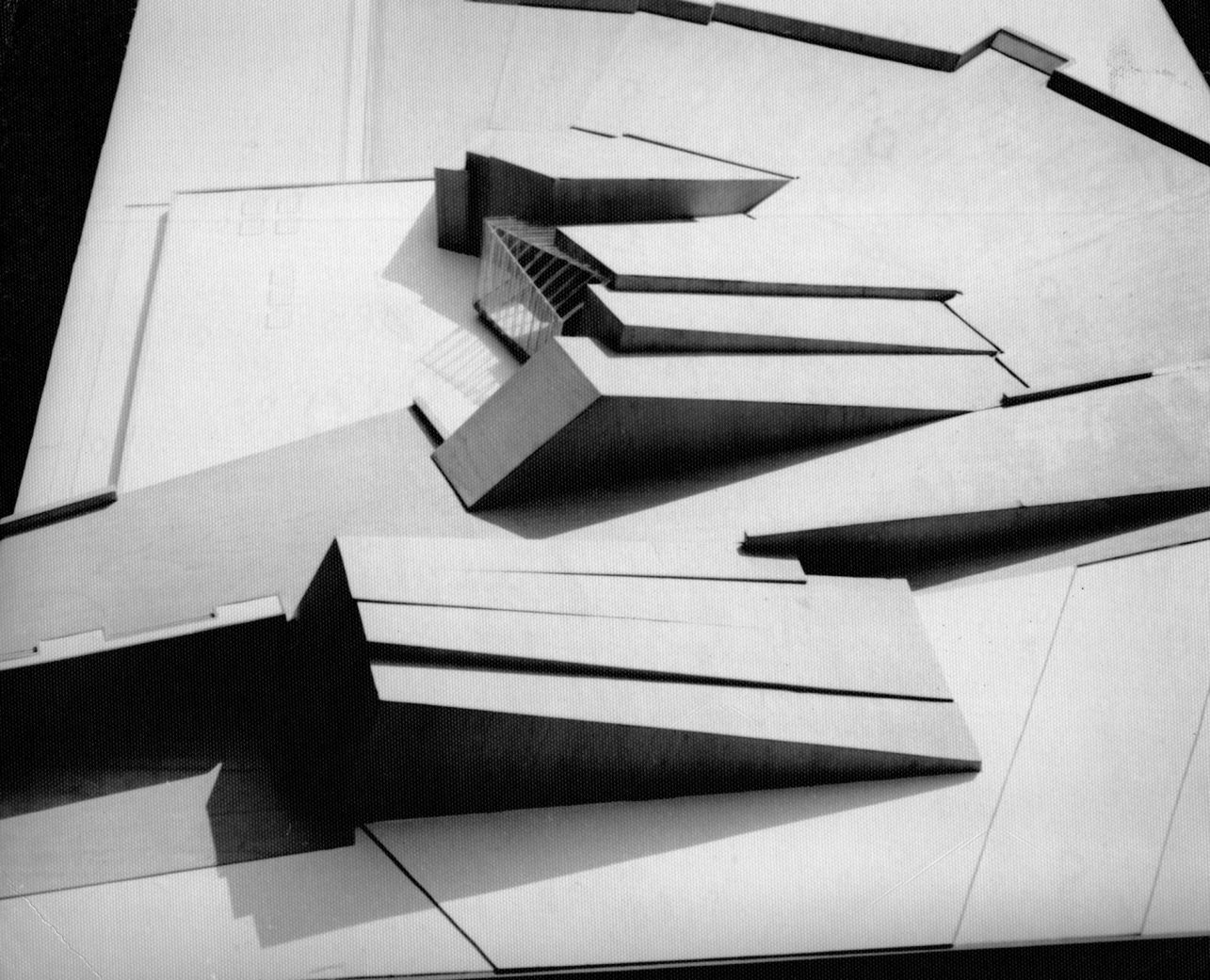

“To build something grand, grandiose and impressive” – this was the demand of the ruling party’s nomenclaturalists for architects. The entire memorial ensemble had to speak of the struggle against Nazism, the heroism of the Soviet citizen and the losses. The project for the construction of the memorial was approved after four rounds of competition in 1966-1970. As many as sixty projects were submitted.

Sculptor A. V. Ambraziūnas and architect Vytautas Adolfas Vielius participated in all four rounds, and they were joined by architect Gediminas Baravykas from the second round. In the spring of 1976, the jury decided that the project by these three artists, with an estimated value of seven million roubles, was the best. The difficult and responsible process of the construction of the memorial ensemble began.

Monument

The main feature of Kaunas Ninth Fort Memorial is a sculpture of exceptional architecture, symbolically known as a monument of the epoch, commemorating the victims of Nazism. The gigantic monument was erected in this space for a reason. The grey, bullet-riddled walls, the cold walls of the cells, the frightening hum of the metal staircase and the inscriptions on the walls in various languages of those who died are the poignant exhibits that have marked the tragedy of a painful loss in the history of Lithuania.

The construction of the memorial was entrusted to the specialists of Kaunas State Second Construction Board headed by Jurgis Žaliaduonis at the time.

Approximately 6,000 cubic metres of top-quality concrete were used for the monument. Perlite, an insulating material, was used to fill the holes inside the sculptures. A tower crane bought in East Germany (Soviet-controlled territory of Germany) for the construction of the monument rotated around the construction site. The welders who constructed the monument’s reinforcement and prepared the formwork for the carpenters had a particularly responsible job. The sculptural fragments designed by the architect had to be joined and fixed to the steel structures. Noone in Lithuania had ever built a concrete monument of this size, and the atypical professional ideas were a headache not only for the design team and the builders but also for the Communist authorities. The representatives of the systemic party nomenclature were constantly interested in how the project was implementing the programme of socialist realism. After the first part of the monument was completed, representatives of the communist government came to the construction site of the Ninth Fort Memorial to check the result. Those who saw the monument could not hide their disappointment, as they had expected a different monument. Ambraziūnas had to listen to the undeserved criticism of Sigizmundas Šimkus, the head of the cultural department of the Central Committee of the Lithuanian Communist Party (LKP CK), and Lionginas Šepetys, the secretary of the LKP CK. The reaction of the Kremlin regime was also a source of fear among Lithuanian party circles. When fragments of the monument with comments on the construction of the brutal monument in Kaunas Ninth Fort appeared in the communist daily newspaper Pravda (“Truth”), a strong demand was received from Moscow to stop the construction. The creators of the monument had to explain and defend their idea at length. Finally, A. V. Ambraziūnas managed to ingeniously state the key postulates of Soviet ideology and justify his decisions in his explanation, and the political uproar settled down.

For several years, the sculptor had to work on the monument, which was surrounded by scaffolding, cranes and concrete pumps, with patience. Gradually, as the planes revealed just one or another detail, one had to try to feel and imagine the whole. In order to achieve plasticity, it was necessary to look for new technological tools and mobilise the designers’ forces in order to achieve the complex forms of the monument. The construction of the Ninth Fort Monument was also slowed down by unpredictable situations. The deaths of the leaders of the Soviet Union unexpectedly occurred one after another. Yuri Andropov, who took over as Party General Secretary in 1982, inherited a difficult political situation: the military invasion of Afghanistan required many financial and economic resources. In order to stabilise the economic situation and reduce corruption, he issued an order requiring a halt to the construction of architectural monuments throughout the Soviet Union. However, the efforts of the local communist authorities (meetings, conferences or formal and informal talks with Moscow) broke the ice and it was allowed to complete the construction of the monument.

People

The work of sculptor A. V. Ambraziūnas is mainly associated with wooden sculptures. The artist’s style was shaped by the tradition of Lithuanian folk carving, which is characterised by an expressive, laconic and rough form and precise characterisation of characters. The stylised large human faces, hand silhouettes, combinations of bodies and plane surfaces depicted in the monument are indeed reminiscent of wood carvings. The sculptor’s idea was materialised by the craftsmen of Kaunas “Dailės” enterprise, which produced the most complex details of the formwork. The main work was carried out by Pijus Krušinskas, a senior craftsman at “Dailės” enterprise.

In the history of the construction of the monument during the communist dictatorship, an inconvenient and intriguing fact was omitted from the history of the monument’s construction, which was recalled by Krušinskas’s son Leopoldas Krušinskas. When talking about his dad, he mentioned a very important fact: Pijus Krušinskas was a political prisoner who was arrested by the Soviet security in 1946 for his connections with the partisans. He served his sentence in the camps of Uchta (Komiya Area) and Balkhash (Kazakhstan), and returned to Lithuania illegally in 1956 with forged documents. L. Krušinskas believes that his dad could have become a famous artist, but the war deprived him of this opportunity. In 1942, Krušinskas was enrolled in Kaunas School of Fine Arts and Crafts, but he only studied for one year because he had to start hiding from 1943, when sending people to Germany for forced labour started. He probably inherited his talent as an artist from his father Konstantinas Krušinskas, who was known as a very skilled blacksmith and a talented woodcarver in interwar Lithuania, not only in the area of Kazlų Rūda, but also in other regions. The most interesting thing about this story was that when Krušinskas was invited to work on the construction of the monument, he had two conditions: he had to be allowed to visit a foreign country and be able to get a warrant for a car, a ‘Žiguli.’ Despite the Communist ideology and ambitions, the party nomenclature accepted the conditions of a former political prisoner sentenced by the Soviet security under Article 58-1a. In 1978, P. Krušinskas visited Bulgaria, and after the construction of the monument had been completed, he received a warrant for a car. This absurd situation suggests that the monument was a project of particular importance and extreme complexity, the implementation of which was a Hamletian question of ‘to be or not to be.’

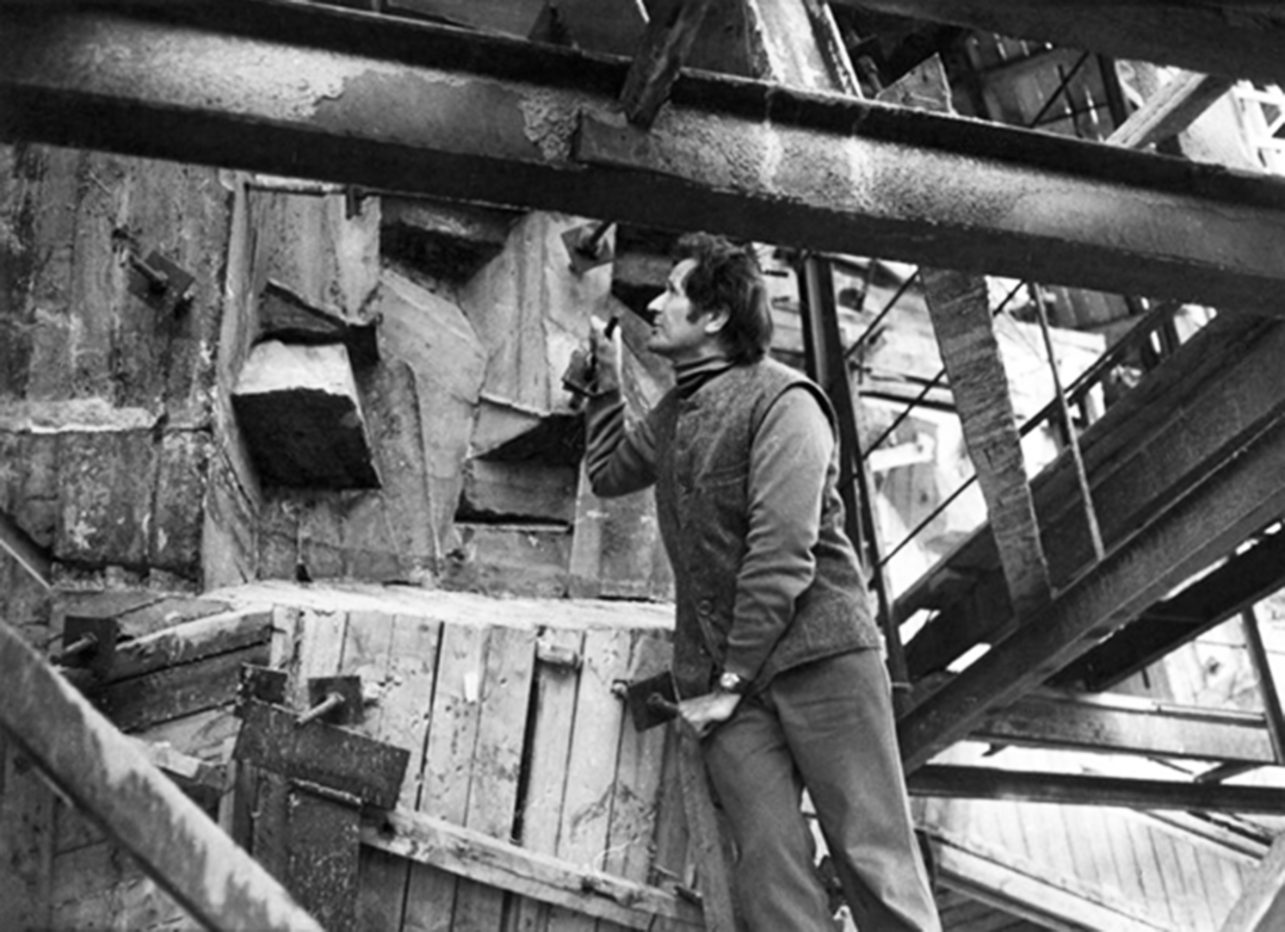

P. Krušinskas, together with pupils from J. Naujalis and M. K. Čiurlionis art schools, enlarged the scale of the monument’s drawings using a pantograph. They made three-dimensional models of the figures from plaster, and then used the templates to make the formwork. The formwork was made of unvarnished wood at Kaunas Žaliakalnis Oak Pavilion in order to achieve the texture of the material characteristic of brutalist sculpture. The complex figural compositions of the monument (faces and hands) were moulded in life-size plaster.

Liudvikas Kvietinskas, a long-time employee of the museum, who was the chief engineer of the construction of the complex at that time, told about the risks, threats and funny situations at the construction site of the memorial: “One day I come to work, and the roof of the museum is on the ground. The concrete slabs of the roof had slipped off, unable to withstand the load due to the steep slope. I had to dismantle the roof and find a safe and durable means of fixing the concrete slabs.” The project did not properly assess the reliability of the building materials used, weather conditions and logistical problems, which slowed down construction. Much work was being done at the same time; therefore, incidents, disputes or strange and absurd situations had to be faced. “When there were major breaks between the construction work, whoever wanted to be the ‘host’ would become the ‘hosts’,” said L. Kvietinskas. “A few times, the walls that had just been bricked up were knocked down, and the materials left on the construction site were stolen.” According to him, in order to manage the risks, it was necessary to coordinate construction schedules and maintain order on the site, and it was very important to ensure the safety of the workers when building several objects simultaneously. It was also necessary to find a compromise when the project authors’ ideas conflicted with the concept of the museum building. “How much sense and understanding was needed to control one’s emotions, which were aroused by the political situation of the communist nomenclature of the time!” he added at the end of the interview.

In his autobiography “Basics of Deconstructivism,” A. V. Ambraziūnas wrote about the construction the following: “<…> The road from the beginning to the end was covered with thorns <…> it was a physically and mentally exhausting way forward <…> the problems arose working with the constructors, who faced the untried engineering solutions and the application of new technologies.“

“Echo of a world falling down and rising up again“

The story of the creation and construction of the monument took almost two decades. The opening ceremony of the memorial took place on June 15, 1984, according to a pre-arranged scenario. The oratorio “The Bells of Remembrance” by composer Rimvydas Žigaitis, based on the poems by Eimuntas Nekrošius and created for the opening of the monument, was performed.

The opening ceremony of the memorial. 1984, Collections of Kaunas Ninth Fort Museum (KDFM 4757, 4758)

The connecting and organising element of the memorial’s compositions is a pedestrian path lined with granite slabs that leads through the death field, stopping at the most important places of the memorial. Many people who can no longer say anything, no longer remember anything and no longer walk back walked along that path. It is important that the visitor remembers and respects the memory of the victims of Nazism when walking along this path as well as appreciates the spiritual and physical harm caused by the war to mankind, and understands that the war victims were not only human lives and broken destinies, but also devastated nature, burnt forests, fields full of landmines and explosive fragments.

At the beginning of the path, a pyramid-like museum building emerges as if from the depths of the earth: an original structure of rough reinforced concrete with geometric shapes created by moulded patterns. The monumental structure is linked by architectural forms to the sculptural monument at the site of the mass murder. Inside the building, on the concrete walls, there are distinct features of brutalist architecture, such as the imprints of unfinished planks and wood strips. The museum’s individuality and special significance are underlined by exceptional works of art: the impressive 200 square metre stained glass window “Lithuania Undefeated” by artist Kazis Morkūnas, commemorating the horrific crimes committed at the Ninth Fort, and the handmade sliding decorative wrought-iron gates by blacksmith Leonas Glinskis, which are decorated with motifs of thistles and a barbed fence.

Once the door of the museum is closed, the path leads to the hill near the Ninth Fort building, where a dramatic clash between the present and the past takes place. Thousands of destinies were shattered here, and tens of thousands of lives were ruined. It is like the abode of the ghosts in Dante’s Inferno, “where they are constantly distracted by a great whirlpool.” The painful blows of fate are marked by authentic inscriptions on the walls of the cells: “I am from Telšiai, (…) Paris, (…) Amsterdam …”. The people who met death here left a trace and a reminder for future generations that this must not happen again.

On the hillside, the road is crossed by the stone pavement that was the last route taken by those condemned to die. The road passes through the walls of the fort, which have been shattered by bullets, and leads to the culmination of the ensemble, the mass murder site. Here, the path abruptly breaks off. As if out of the flattened and corroded earth, a monument resembling a dramatic painting rises to a height of thirty-two metres, a monument to those whose blood soaked Lithuania’s land here and elsewhere. The composition of the figures evokes a variety of emotions, from grief and sadness to determination and hope and from pain to the indomitable fighting spirit. Sculptor A. V. Ambraziūnas called the monument “The echo of a world falling down and rising up again.”

As the seasons change, the shadows and halftones that fall on the monument change according to the movement of the sun across the sky during the day, and the features of the faces and hands carved on the monument become more prominent and visually magnified. As the sun changes direction, the shifting shadows create the image of another world: faces and hands clenched into fists disappear like human lives leaving time to reach eternity.

Message to the world

No one else in Lithuania has created a monument of this size. It is difficult, if not impossible, to accurately convey the creative process of sculptor A. V. Ambraziūnas as well as to answer the questions of how, in what way and with what emotions the artist was able to give life to the faces of the people frozen in a reinforced concrete monolith, which speak with a unified voice of the prayers of the dead reminiscent of their deep pain. One thing is clear: the successful result of the creative work (i.e. a magnificent monument distinguished by originality and professionalism) was created because of the artist’s self-confidence, intuition, creative experience and persistent work.

In 1985, the authors of Kaunas Ninth Fort Memorial (sculptor A. V. Ambraziūnas, architects V. A. Vielius and G. Baravykas) were awarded the state prize by the decision of the Soviet Union’s Council of Ministers and the Communist Party.

Currently, the Memorial is considered to be an internationally significant monument of the era, listed as one of the world’s most visited tourist attractions by the United Nations World Tourism Organisation (WTO). Kaunas Ninth Fort Monument, which is among the world’s top thirty monuments to the victims of Nazism, today takes on an even deeper meaning, becoming a memorial not only to those who were murdered in the Nazi concentration camps, but also to political prisoners who did not return from the Stalinist camps, and commemorates the fate of the deportees in the land of eternal frost. In the words of the sculptor, A. V. Ambraziūnas, this monument is a contribution to peace.

Kaunas Ninth Fort Memorial makes the thousands of people who visit the museum and stop at the monument think about the present and the future, about how far a person can go in spreading racial, religious and social hatred, disinformation, religious fanaticism or discrimination against other nations, and invites them to refrain from being accomplices and instigators of war crimes.