During the Second World War, when Lithuania was occupied by Nazi Germany (1941-1944), Kaunas Ninth Fort became one of the largest Holocaust sites in the country. Thousands of Kaunas Jews were murdered here, as well as foreign Jews deported from Germany (Munich, Berlin and Frankfurt am Main), Austria (Vienna), Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic), Poland (Breslau, now Wrocław) and France (Dransi transit camp) were systematically killed here.

The so-called “foreigners’ actions” are a common tragedy linking Kaunas and these European cities. It highlights the need for cross-border cooperation in historical research and the preservation of the memory of the Holocaust. The preservation of the memory of the genocide obliges us to remember not only the facts and statistics, but also to investigate what lies behind the numbers of victims: the individual personality and the different life story.

In March, 2025, a visit was made to Munich City Archives (Stadtarchiv München), where the material related to the Jews deported from Munich in November 1941 and murdered in the Ninth Fort was collected. This article shares some of the discoveries made in Munich.

In the archive, the Judaica collection was analysed, which contains photographs of Jews and their families from the late 19th to early 20th centuries, personal correspondence (letters, postcards) and works of art. A significant part of the information collected consists of documents related to companies and businesses owned by the victims and their “Aryanisation” (transfer to non-Jewish owners).

On November 20, 1941, a group of almost 1,000 Jews was deported from Milbertshofen railway station (Munich) to the east. A few days later, on November 25, they were murdered, together with Jews from Berlin and Frankfurt am Main, in the first “Foreigners’ Action” in Kaunas Ninth Fort. It was not only a brutal but also an unexpected death.

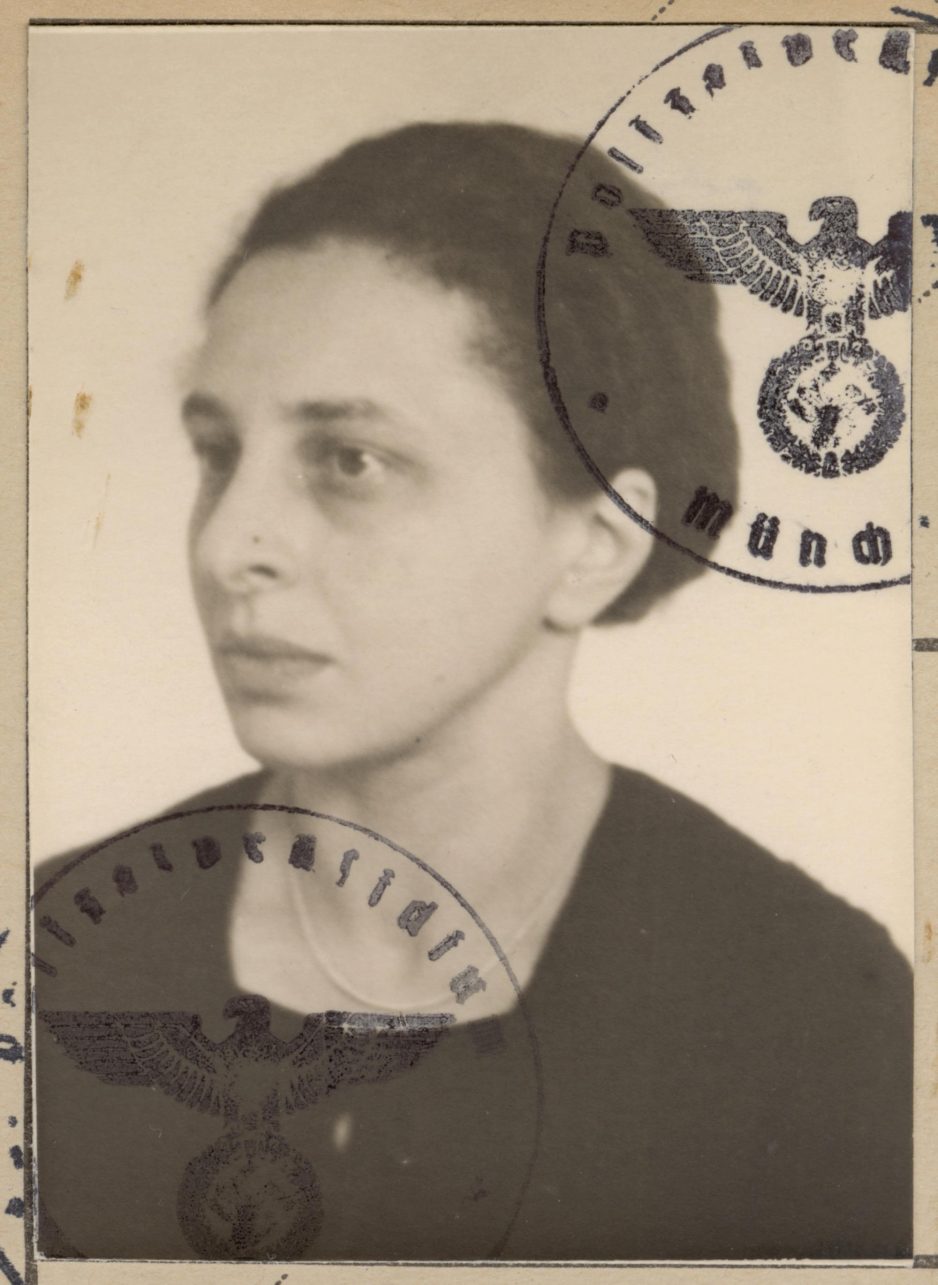

A considerable part of German Jews considered this country to be their home; they were its citizens and patriots. They successfully assimilated, worked, intermarried and forged close ties with the non-Jewish population. The friendship between the Jewish woman Kitty Neustätter-Herz and her German friend Friedel Lahs is one of such examples. Kitty was born in Vienna in 1902. Her family was brought to Munich in 1919 by her father Otto Herz’s work interests. He was appointed as a representative of the company Phönix-Lebensversicherung (Phoenix Life Insurance), and from 1923 he held the position of the director of the company in Germany. During this period, Kitty studied economics at Ludwig and Maximilian University of Munich, but did not finish her studies when an attractive job opportunity arose. She became a secretary to her father, who was in a very high position, and an assistant who accompanied him to charity events and business trips. It is likely that during these trips she met her future husband, the Jewish businessman Rupprecht Felix Neustätter (born 1900). The couple married in 1928.

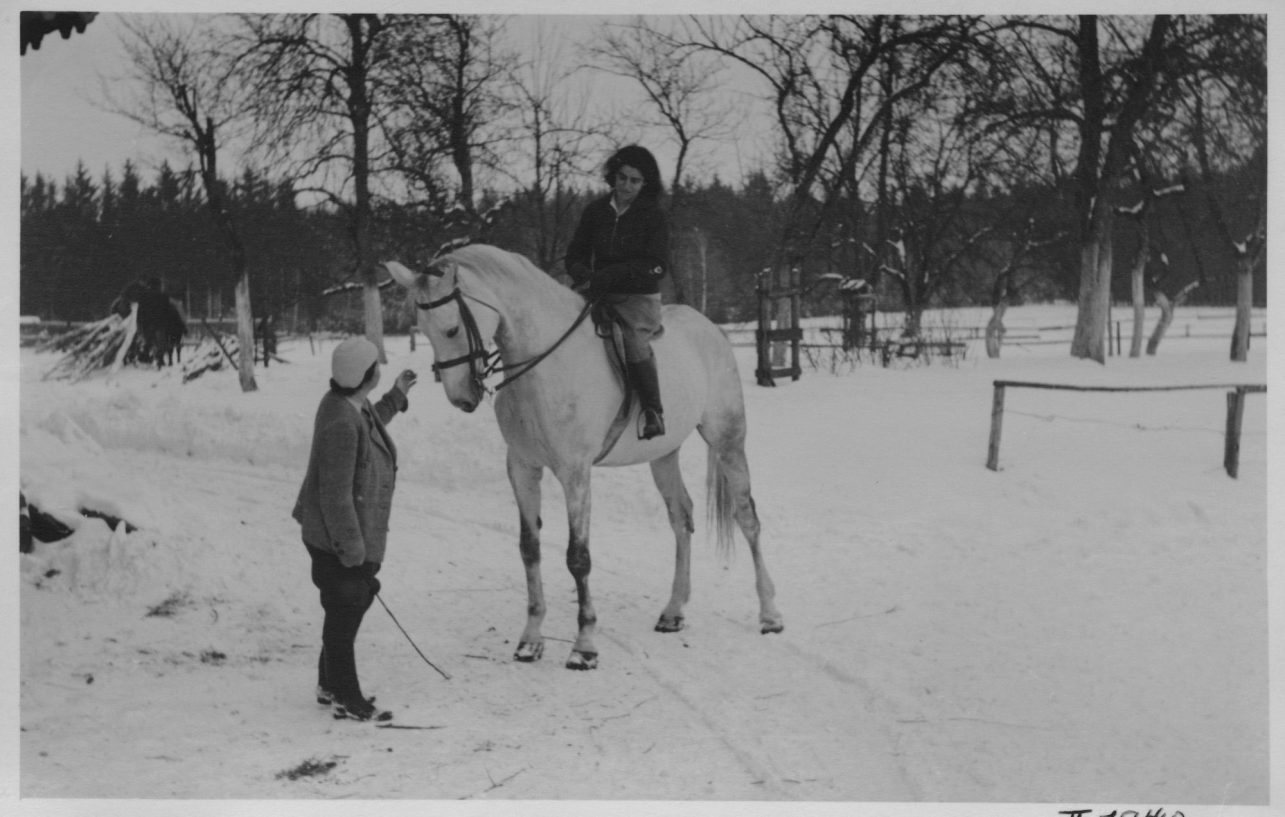

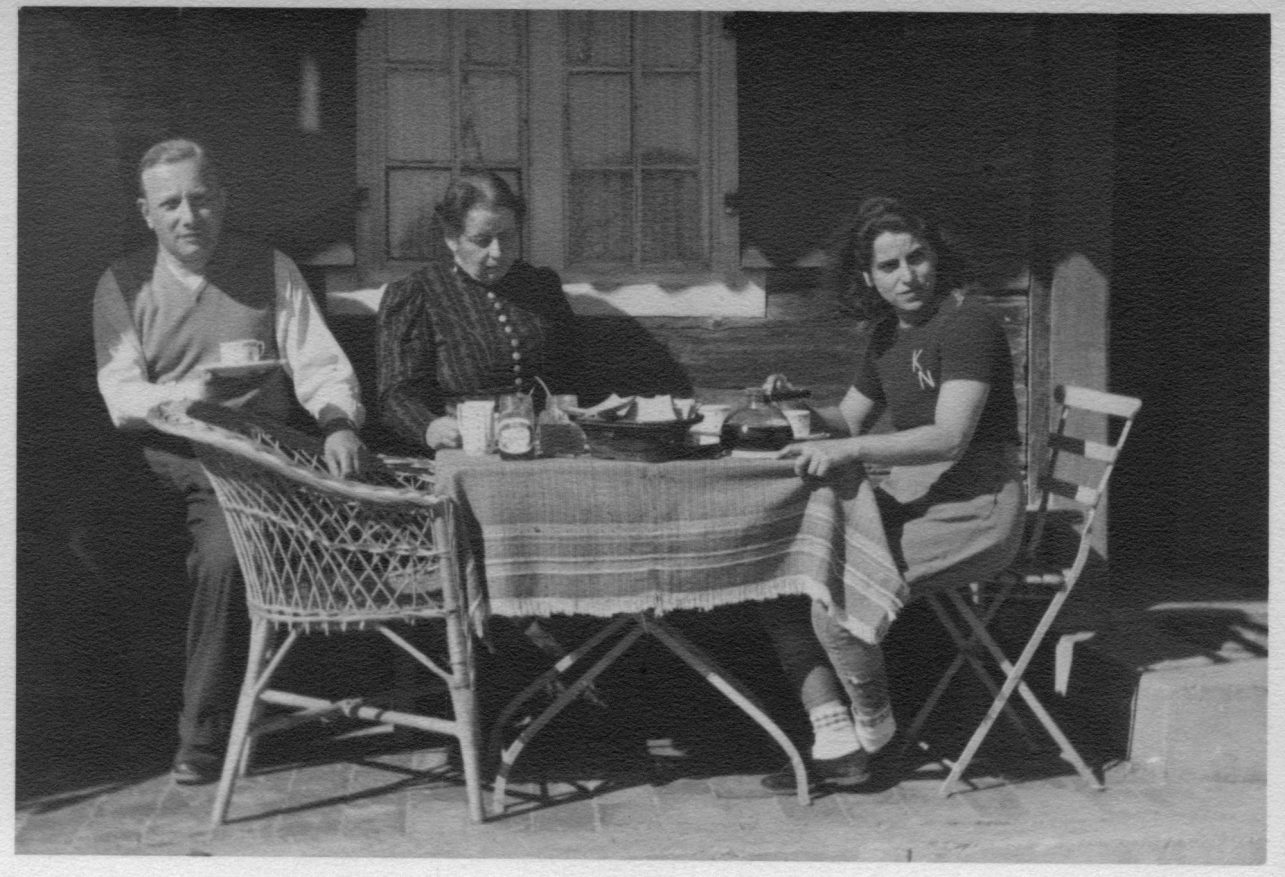

Kitty’s main leisure passion was horse racing. She took part in horse tournaments and races and met Friedel Lahs, an experienced rider, in this environment. The shared hobby led to a friendship between the women. From then on, Kitty and her husband became frequent guests at Friedel’s farmhouse, set in the picturesque Bavarian countryside around Lake Starnberg. Ruprecht was not a horse sports enthusiast, but loved to record his wife’s leisure. Therefore, there is quite a large amount of footage and photographs of Kitty and Friedel. Mainly, these are moments of the women being active: riding, skiing, caring for horses and other animals. The photos and videos cover the period of quiet, carefree and happy days before the Nazi terror and the threatening and fearful period of the persecution of the Jews. However, the material does not reflect this turning point.

The Nazi takeover of Germany in 1933 fundamentally changed the lives of Kitty and Ruprecht. In the same year, Kitty’s dad Otto had to leave his director’s position because of his Jewish background, and in 1938 the Ruprecht family was forced to sell the business. Growing anti-Semitism eventually reached the area around Lake Starnberg. The mayor of the nearby town of Sankt Heinrich began to urge Friedel to break off contact with friends. Despite the growing hostility and hatred towards Jews, the woman did not give in to the pressure. Her bond with Kitty and Ruprecht was stronger than the anti-Semitic propaganda. In 1939, Friedel bought a remote farm where her friends continued to spend time. It was the last oasis of a quiet and happy life for Kitty and her husband. During this period, the couple were preparing to emigrate to Australia and were awaiting the necessary permits to enter the country. However, the paperwork took too long. In October 1941, the ban on Jews leaving the Third Reich came into force, making emigration no longer possible. On November 20, 1941, Kitty and Ruprecht, together with other Munich Jews, were deported to their deaths on a train bound for Kaunas. The doomed did not know their fate; therefore, Friedel and Kitty believed that their communication would continue by letters.

However, Friedel never received a message from her friend, but she never forgot her. The woman preserved and passed on to her descendants the material entrusted to her by Ruprecht, which captured the brightest days of his wife’s life. Today, the memory of Kitty and Ruprecht is cherished by Friedel’s daughter and granddaughter. The latter, undoubtedly stimulated by the personal connection she feels, is carrying out research and is involved in the production of documentaries on the fate of her grandmother’s friends.

Nearly one thousand unique life stories can be told about the deportees from Munich. Some of them are remarkable because they involve bright, talented and artistic personalities. One of them is artist Marie Luise Kohn, born in Munich in 1904 to Jewish businesspeople Olga and Heinrich Kohn. She had a sister, Elisabeth, who was two years older.

Although the sisters chose very different career paths, they were both talented and successful in their fields. The younger Marie Louise was an artistic soul, but first, perhaps at the urging of her family, she trained as a nursery teacher. She did not choose this path in life because she was drawn to creativity. From 1923 onwards, she began to study painting and graphic arts, and took theatre classes. The following year, her work was exhibited for the first time in the old botanical garden of the Munich Glass House (Münchner Glaspalast) under the name of Marie Luiko. Marie Louise was a versatile artist whose works include watercolour, oil paintings, lithography, paper cuttings, woodcuts, book illustrations and marionettes. The talent of the young girl did not go unnoticed at the time. Art collectors and buyers were interested in her work, but the road to wider recognition was blocked by the rise of the National Socialists in power.

In 1933, the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts (Reichskammer der bildenden Künste) was founded, which was used by the regime to control artists and promote ideology in art. Only members of the institution were allowed to practise art as a profession, officially exhibit their works and obtain the necessary supplies for their work. As Marie Louise was Jewish, the doors of the chamber were closed to her. The girl’s ability to continue creating and exhibiting was restricted, but not yet lost. In 1934, the Jewish Cultural Association of Bavaria (Jüdische Kulturbund in Bayern) was founded in Munich to bring together Jews who had been excluded from cultural life. After joining the association, Marie Louise not only exhibited her works for a Jewish audience, but also took a new initiative. Together with her colleagues, she founded the Munich Marionette Theatre of Jewish Artists (Münchner Marionettentheater Jüdischer Künstler) where she designed stage design and marionettes.

At the heart of Marie Louise’s work is the human being. In the early 1920s, her work is dominated by family, children and social themes (mostly depicting ordinary workers and labour scenes). However, in mid-1930s, the content of her work is influenced by the changed political situation and anti-Semitism. In her works, religious motifs can be noted and attention is devoted to the themes related to the Jewish people and the threat to them.

Unlike Mary Louise, who had an artistic nature, her elder sister Elizabeth chose a much more defined field – law. From 1928 onwards, her career took off and she became one of the first three women to be admitted to the legal profession in Munich. Soon after, Elisabeth joined a law firm specialising in political criminal cases, and in the courts the staff often had to deal with members of the Nazi Party. It was their rise to power that led to Elizabeth’s licence as a Jewish lawyer being revoked in 1933.

For several years (1940-1941), Elizabeth worked as an assistant in a law firm dealing with Jewish clients. Her main activity was to help Jews trying to leave Germany. Her letters reflect the emotionally difficult atmosphere of this period, with a great responsibility to ensure that as many people as possible were able to leave, and a great deal of inner strength required to work in the midst of desperate clients. Meanwhile, Elisabeth and her sister Marie Louise had long delayed their decision to emigrate from Germany. They did not want to leave their widowed mother; also, the journey for three people was complicated and costly. Elisabeth’s letters reveal that when she considered the possibility of leaving for at least one person in the family, she was prepared to save her sister. She was convinced that life under the Nazi terror was extremely difficult for Marie Louise, a much more sensitive personality. Eventually, permission was granted for the whole family to emigrate to Cuba, but the ban on Jews leaving the Third Reich meant that it was too late to save them. Marie Louise, Elisabeth and their mother Olga were deported and executed at the Ninth Fort in Kaunas on November 25, 1941.

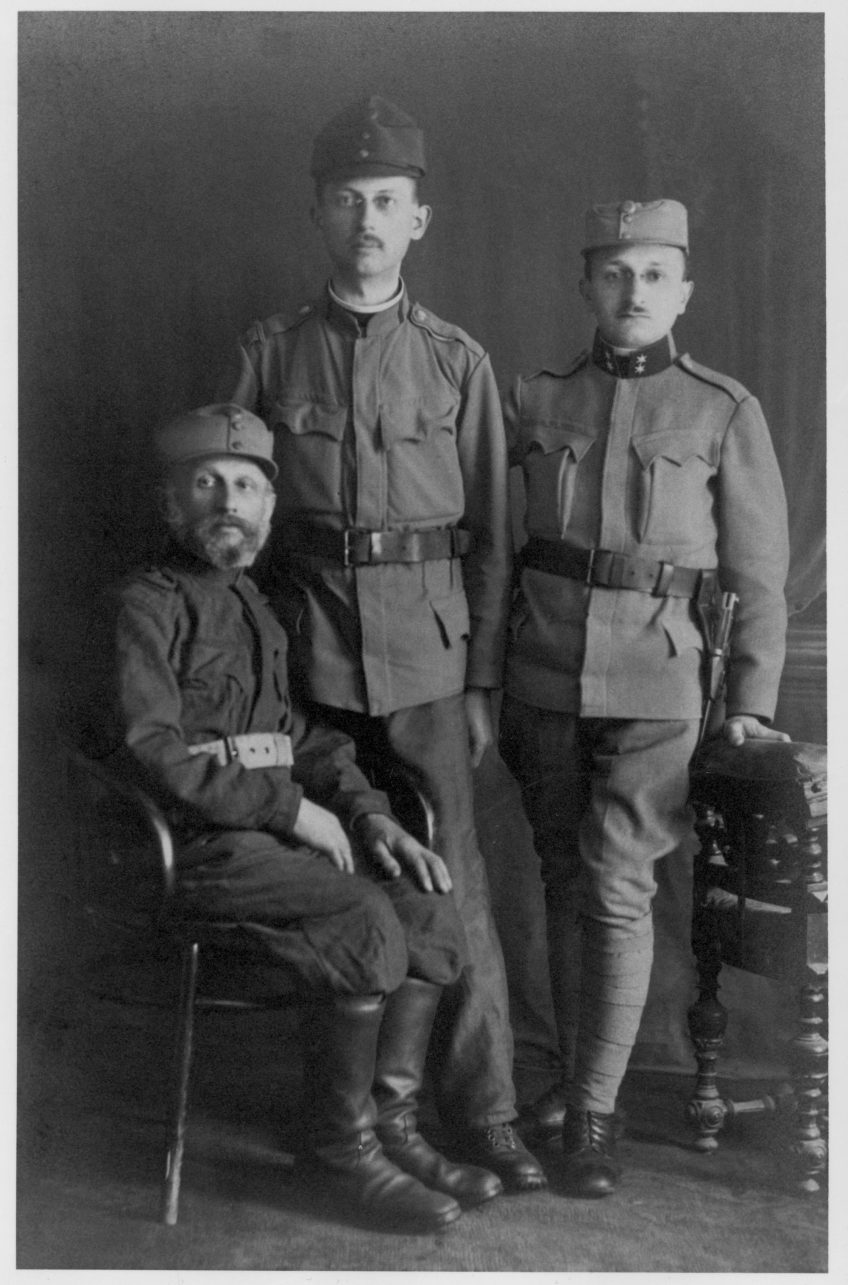

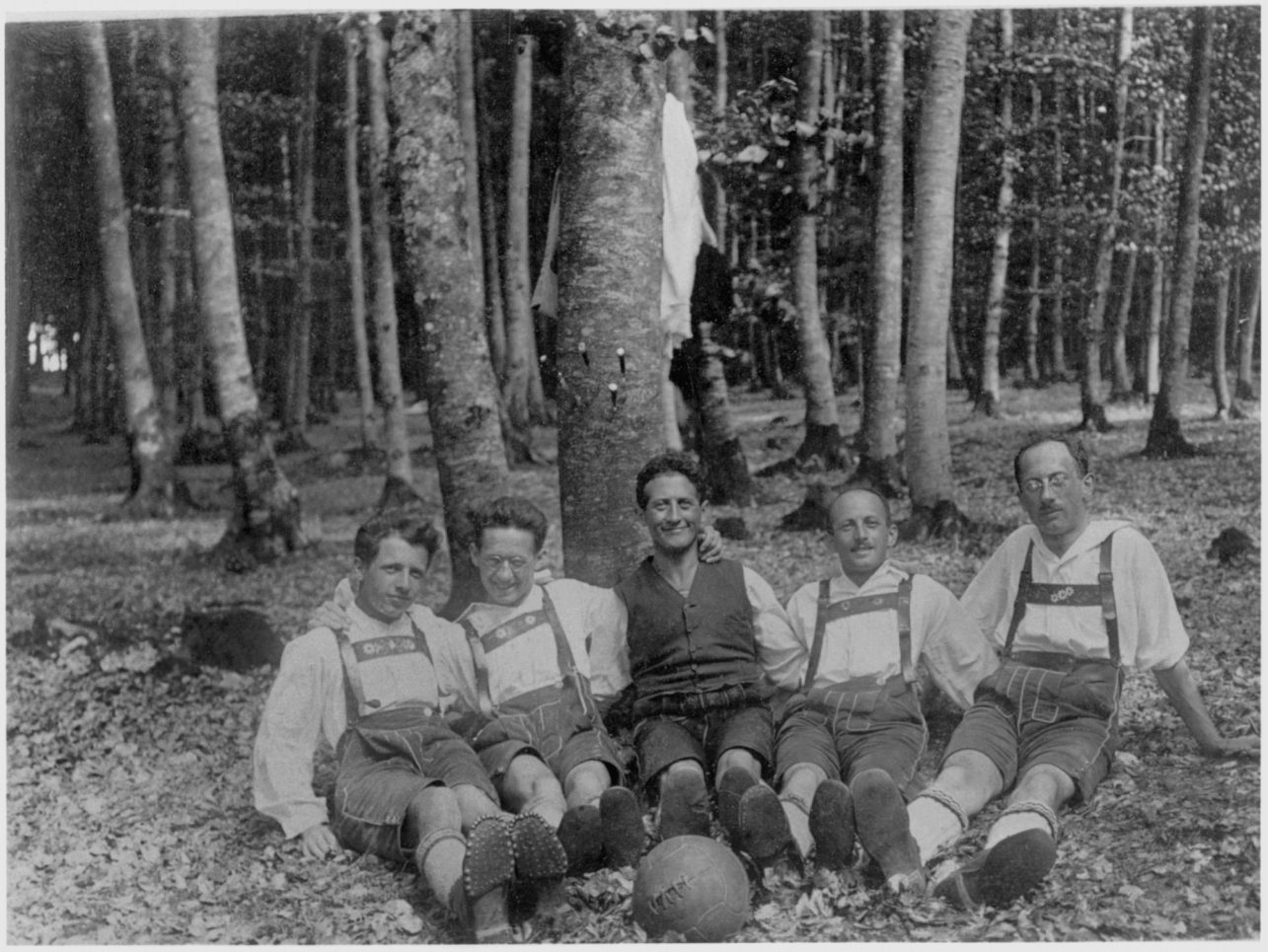

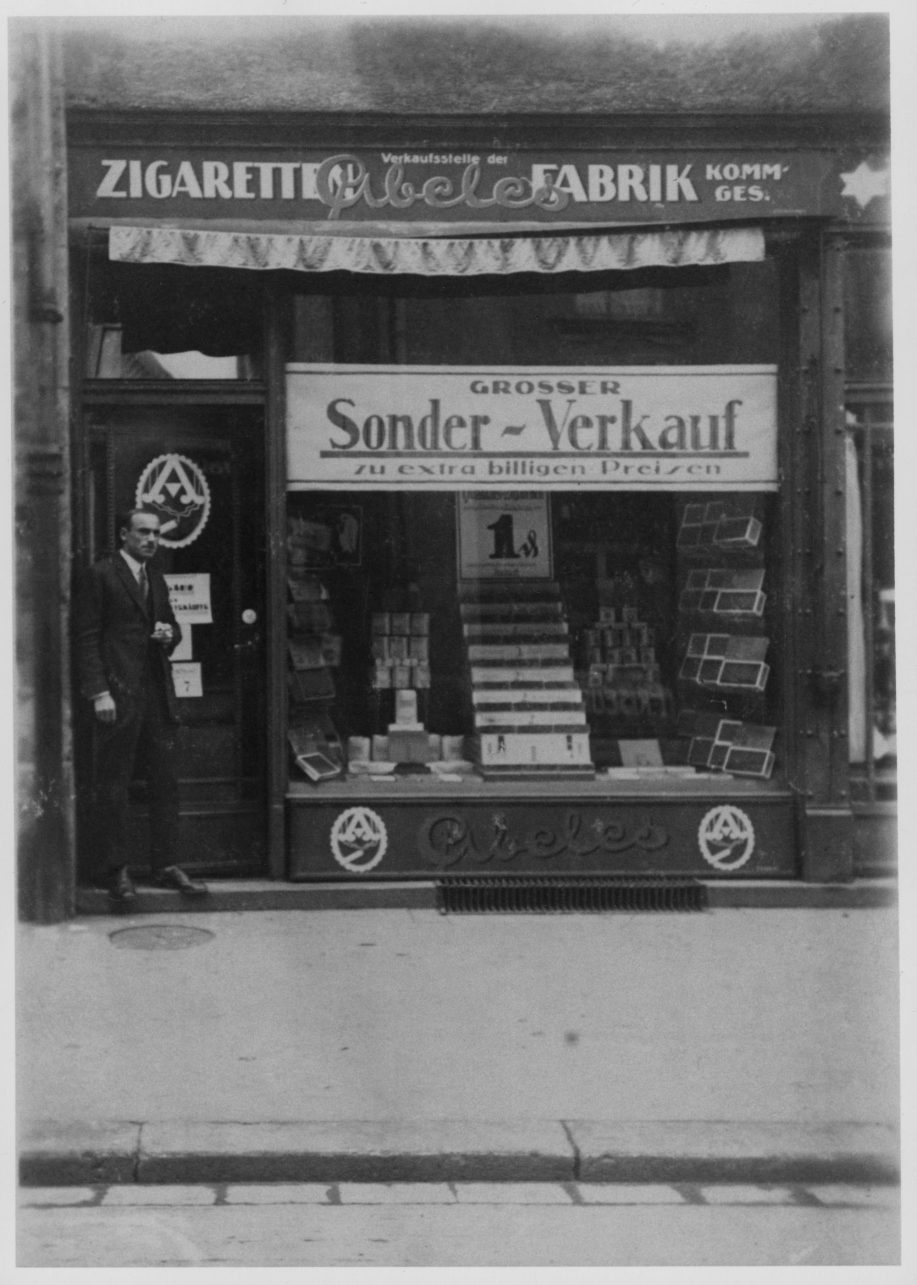

An analysis of the biographies of those who were killed shows that many of those deported were traders and businessmen. This largely reflects the fields in which the majority of Jews in Germany worked in the early 1930s. With the onset of Hitler’s dictatorship, Jews were pushed out of economic life through discrimination, restrictions and laws against them. Under these circumstances, Jews were forced to give up their source of income and sell their property at a lower value to non-Jewish citizens. One of the many victims was the Abeles family. Max (b. 1865) and Dorothea (b. 1867) Abeles moved to Munich in 1897 from the town of Chiesch in West Bohemia (now the Czech Republic), where they founded a cigarette and tobacco factory Zigaretten & Tabakfabrik Abeles GmbH. The company eventually became a thriving family business, with four of the eight children – Friedrich (b. 1892), Ernst (b. 1895), Eugen (b. 1897) and later Otto (b. 1902) – working for the company.

The first-born, Friedrich, managed several branches of the family business. In 1927, he started his own business, registering the wholesale and retail sale of tobacco, opening a tobacconist’s shop and later two branches. The business was a success, with annual sales in one of the shops exceeding 100,000 marks in 1936. However, as the situation of the Jews in Germany was getting worse, Abeles sought to sell the business in 1938, but without success. In November, during the Crystal Night pogroms, his tobacconist’s shop was vandalised and officially closed on November10. In 1939, Abeles’s business was deregistered and his inventory sold to Hans Lorenz, a tobacconist, for a considerably lower value. For example, cigars were bought at a 40% discount on the retail price, while tobacco and cigarette paper at a 50% discount on the retail price.

The younger brothers Ernst and Eugen were partners in the cigarette and tobacco factory founded by their father, and Otto became the company’s CEO in 1927. Ludwig Heymann (b. 1897), the husband of their sister Therese (b. 1893), was also working with the brothers and had previously been involved in the art trade. In 1938, like most Jewish businesses, the Abeles company was sold, but no buyer could be found. After the Crystal Night pogroms, the company’s activities were terminated and the business was deregistered. Meanwhile, the family members looked for ways to leave Germany, but not everyone was able to escape. On November 25, 1941, Friedrich Abeles and his sons Oskar (b. 1922) and Walter (b. 1927), Ernst Abeles and his wife Hilde (b. 1895), his daughter Lieselotte (b. 1924), Eugen Abeles and Ludwig Heyman were killed in a “Foreigners’ Action” in Kaunas Ninth Fort.

The life stories of the deportees presented in this article not only reveal the different ages, places of origin and professions of the victims, but also tell the story of those who were murdered as a rather integral and diverse part of German society. This is evidenced by the close relations between Jews and their non-Jewish fellow citizens, and by the activities that enriched the arts, science, the economy and many other spheres of national life. Despite their diverse life paths, the situation of all Jews as citizens changed dramatically since the rise of the Nazis, whose racial ideology rejected the view of a person as an individual. Jews were deprived of their rights and property, isolated from society and eventually murdered, but their memory remained intact. Today, it is cherished not only by the institutions of remembrance, but also by the relatives of those who were murdered, by people who feel a personal connection and responsibility, and it lives on in the creative legacy of the victims.

The possibility to analyse the research material related to the lives of the murdered Jews was provided by the mobility programme “Culture Moves Europe.“ This is an initiative of the “Creative Europe“ programme, funded by the European Union and implemented by the Goethe-Institut, which encourages artists and culture specialists to carry out international projects with a partner of their choice in another country, which is a part of “Creative Europe“ programme.