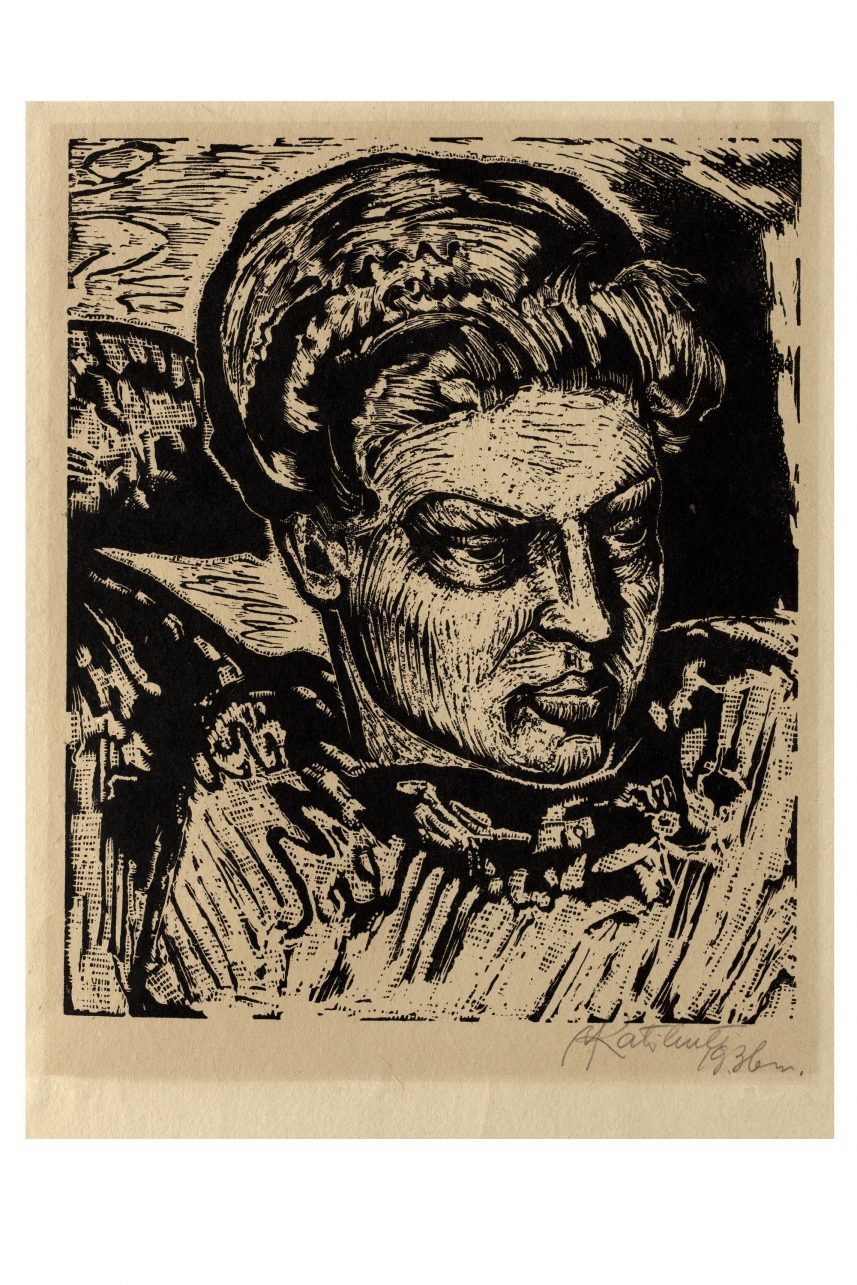

Marcė Katiliūtė’s name and works were engraved in my memory during my studies, learning about Lithuanian modernist art, where a female artist is usually an exception to the rule. The strong, even somewhat stern self-portraits of the artist, the expressive strokes in the carvings, and the prevailing melancholy left an immediate impression on me.

The fact that the artist decided to end her life at the age of 24, after a difficult life full of creativity and challenges, was just as vividly memorized. Therefore, in the September issue of the Kaunas Full of Culture magazine, looking for the female gaze (find all of the articles here), I wanted to present her personality and work. Aušra Vasiliauskienė, the curator of the Graphic Art Collection at the M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art, told me more about Katiliūtė.

Marcė Katiliūtė was born in 1912 in the village of Ivoškiai. She grew up in a poor family with many children. Her father tried to farm and create businesses, but he struggled, so the artist was left to be raised by her grandmother as a child. As A. Vasiliauskienė emphasizes, this can be considered a pivotal point in the development of M. Katiliūtė’s personality, because this period of her life was characterized by a strict, isolated upbringing. By nature, the artist was already an introvert, and this environment strengthened this quality even more. M. Katiliūtės diaries contain memories that her grandmother would only let her out for a short time to the yard gate and then would call her home again, so she didn’t have many opportunities to socialize. Such an isolated way of life shaped her character, and later M. Katiliūtė mentioned that the company of four walls was close to her heart, and short periods of going out were more than enough. Her talent for drawing became apparent in school, and by the end of it, everyone wished her to become a professional artist. M. Katiliūtė herself did not feel the calling right away, her interest in art grew gradually, when she slowly realized that drawing lessons were closer to her heart than other subjects.

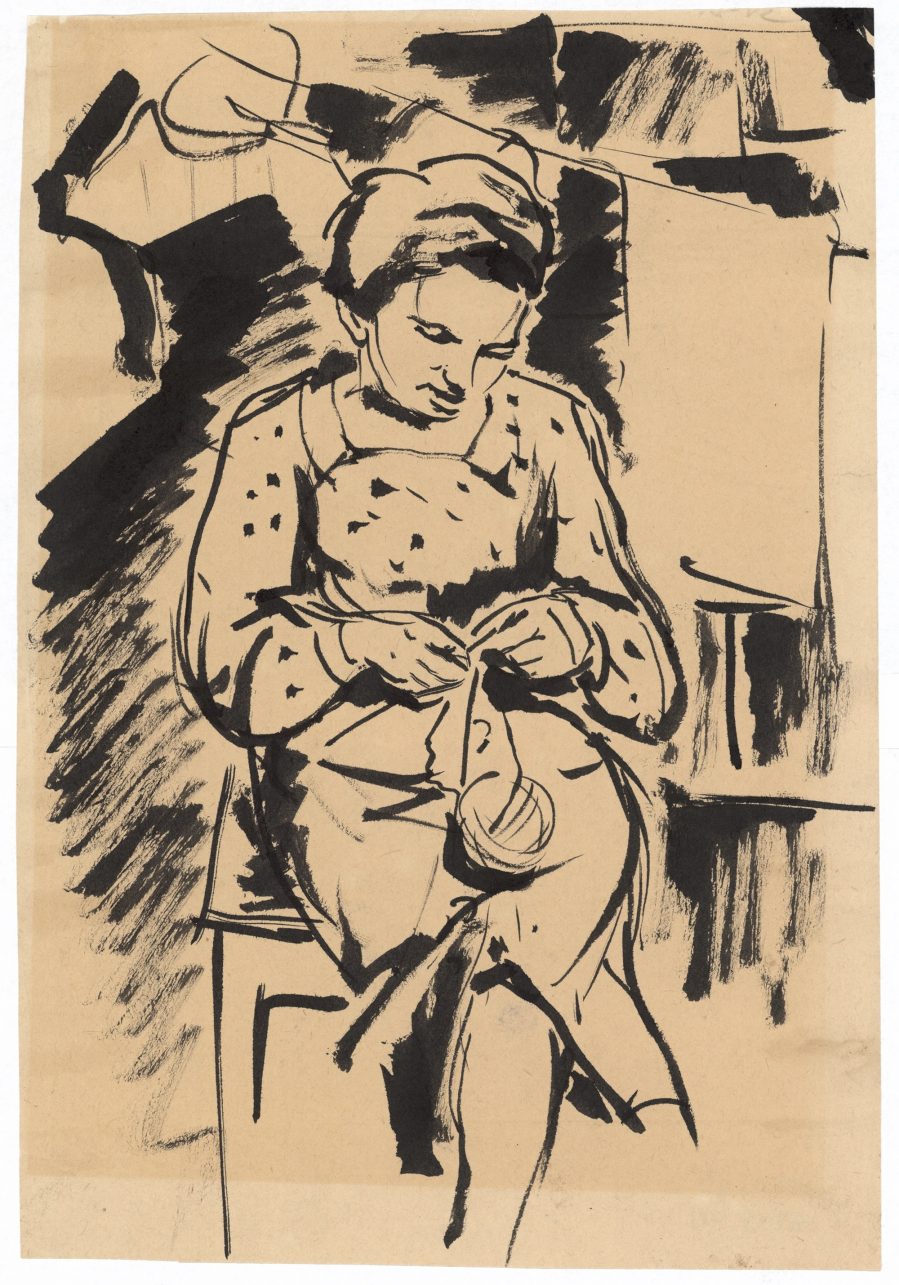

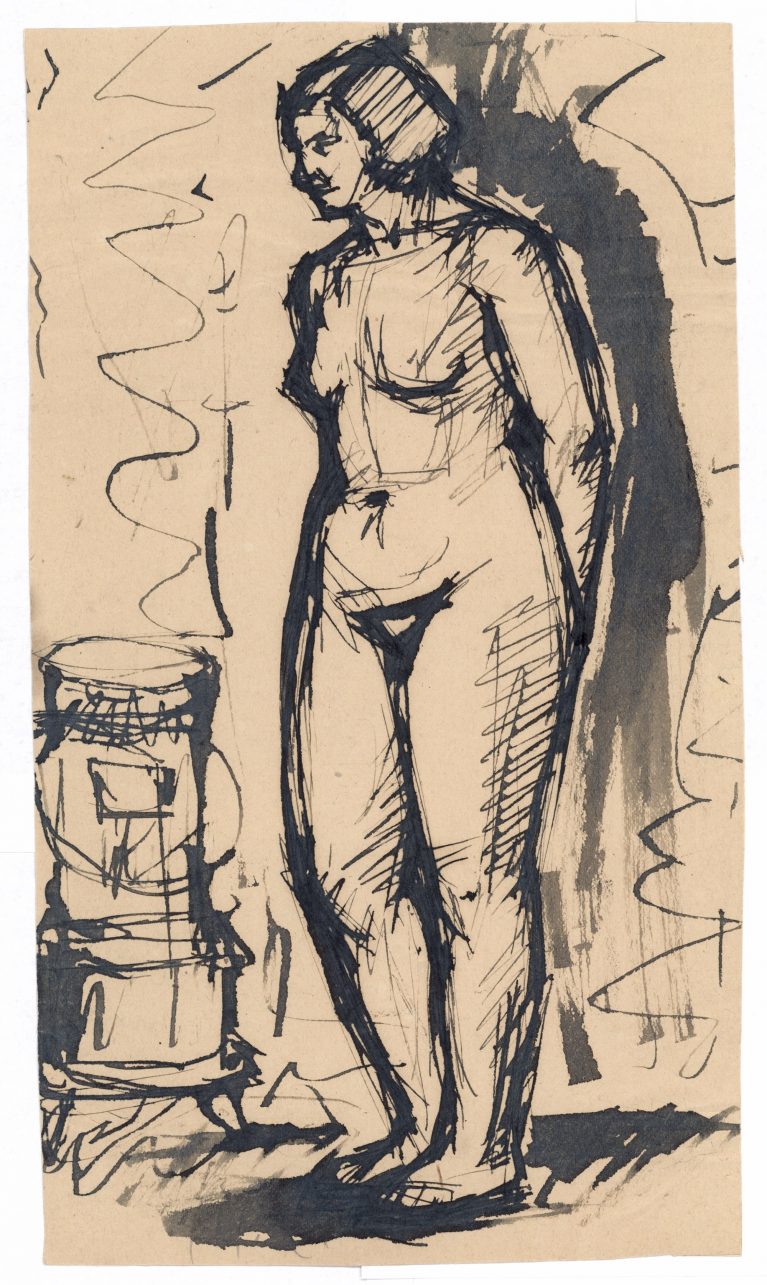

Later, M. Katiliūtė studied at one of the main artist forges of the time – Kaunas Art School, where she studied graphics and painting. During her short life, she created several hundreds of works. Most of them are kept today by the M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art with some collections held by the Lithuanian National Museum of Art and Aušros Museum in Šiauliai. M. Katiliūtės biggest heritage consists of drawings and sketches of ideas but there is also no shortage of finished paintings, illustrations and prints, which most vividly reflect the artist’s talent. “M. Katiliūtė was one of the first artists I got acquainted with when I came to work at the museum. First of all, it was her personality and the tragic fate that attracted and even shocked me. Therefore, I always remember her first as a person with a sensitive soul and a sad life. However, no one could deny that the artist’s works are extremely professional”, A. Vasiliauskienė shared her thoughts.

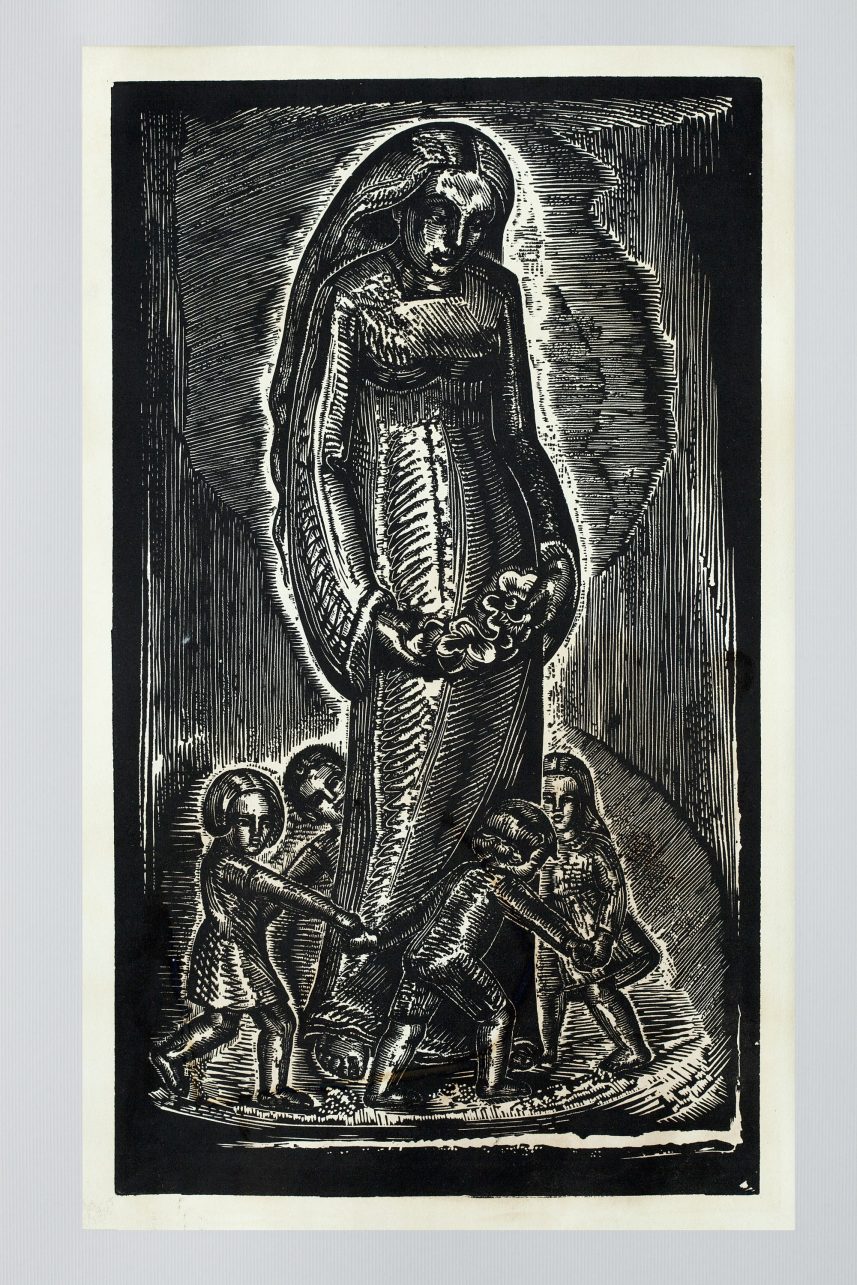

M. Katiliūtė created her most striking works in the late period using the linocut technique, which was the most financially accessible and allowed the creation of bright contrasts and soft lines. In the artist’s works, both through the mood and through subjects, we can feel the echoes of her inner world, difficult life, sadness, and lyricism. Her most solid works include linocuts Urtė (illustration for the book The Fate of Šimoniai Family in 1936) and In the Forest (1936). According to A. Vasiliauskienė, these engravings are seen as a mirror of the soul of the woman of the time as well as M. Katiliūtė herself. Most of the works feature a person, especially a woman, the author herself, and her sister Stasė. There is a strong influence of folk art and folklore motifs and in the rich collection of drawings, one can also notice the environment in which the artist lived.

There were few professional women artists in those days. Although M. Katiliūtė was considered a talented creator, who graduated from the Kaunas Art School with the highest grades and it was recommended that she be given a scholarship to study in France, she never received this support. It is worth mentioning that Lithuanian artists such as Marija Račkauskaitė-Cvirkienė and Domicėlė Tarabildienė studied together with M. Katiliūtė, and they were also recommended to the Ministry of Education for evaluation to be awarded a scholarship for studies abroad, but only D. Tarabildienė later received it.

M. Katiliūtė was always a maximalist, she sought to live only with art and from art, but she constantly had to fight poverty and difficult living conditions. She was not inclined to ask for help or openly share her thoughts, but it is easy to feel a melancholic mood and depressive tendencies in the artists’ diaries. She was very sad when she did not receive the scholarship, she did not want to make any compromises but simply to dedicate herself to her art, however, life forced her to get a job as a teacher in Palanga and also work as a conservator-restorer in Kaunas. “M. Katiliūtė, her personality and creative development reflect the problems of interwar women creators. Although the discourse of that time already included the issues of women’s position in society, these were still only isolated discussions. Female artists were looked upon as freaks, and the traditional view that a woman’s calling was to raise a family still prevailed. So, it should not be surprising that M. Katiliūtė’s tragic fate and personality led to the rallying of female artists in Lithuania,” A. Vasiliauskienė said.

The first exhibition of Lithuanian female artists took place in 1937 also featuring M. Katiliūtė’s works. A year later, female artists’ society was formed, which actively took care of preserving and nurturing the artists legacy. The society organized M. Katiliūtė’s exhibition in 1940 featuring almost 500 artworks. Another evaluation: the artist’s graphic works were awarded a gold medal at the International Exhibition in Paris in 1937. It is disappointing that the author received such recognition and notice after her death, which has been surrounded by rumours both in the society of the time and now. It is being considered whether M. Katiliūtė was pushed to end her life by the society’s critical view of a woman artist, or by a difficult financial situation and the decision to not award her with a scholarship, or by unrequited love. Although it is probably impossible to find the real answer today, this story illustrates how difficult it was for women to survive and establish themselves in society, while not following traditional norms. In addition, M. Katiliūtė’s fate forced the creators of that time to reflect on their situation, gather and discuss. Although the graphic artist herself did not participate in feminist activities, she had the courage to raise the question of whether she did not receive state support because of her gender. Some of her works question the social reality of the time. However, the artist was wholeheartedly devoted to pure art, which she always praised and called “noble holy art”, considered it the light of her life and wrote, “If someone took away art, the opportunity to create from me, I would die with it.”

Although today M. Katiliūtė is probably not the first artist you would think of when you remember the kind of golden age of Lithuanian art in the interwar period, her legacy certainly attracts attention. As A. Vasiliauskienė mentioned, M. Katiliūtė’s works are now actively participating in exhibitions, and several monographs dedicated to her have been written. The M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art currently hosts an exhibition Woman’s Image in Graphic Art of in Kaunas Art School, which features M. Katiliūtė’s works. Her works are unique in this context, because they open a feminine view of women as an art subject, they focus on a woman’s experiences, her inner world.

Looking at the case of M. Katiliūtė, one wonders what would have happened if her life had turned out differently, if she had not faced such challenges because of her gender, if she had received more support. Since the artist left the world at the age of 24, it seems that her potential would only have increased, and she could have given so many more unique artworks to Lithuanian art. We cannot re-write history, but it is worth paying attention to what questions this fate raises, reflect on them today and, of course, discover and appreciate Marcė Katiliūtė’s works, if you haven’t done so yet.