The fear of losing your job fits nicely in the bouquet of worries about climate change and war. Will I be relevant a year from now if I’m feeding the artificial intelligence – which is encroaching on my job position – with my queries today? What should you learn today so that you don’t have to carry an unnecessary burden later? When AI writes a Facebook post or an article for me, should I enjoy my free time or invest it?

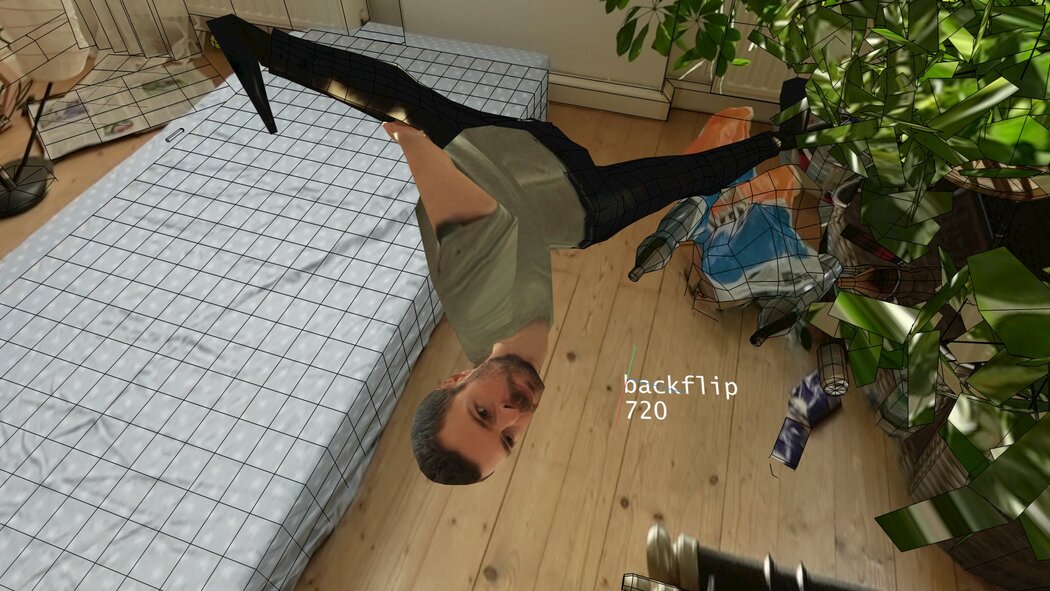

There are lots of questions. The most creative people find the answers to them somewhere along that thin line where it is not clear whether we are dealing with real or virtual reality. Animator Nikita Diakur, for example, turned this anxious state into a work of art, a short film titled Backflip (2022). The story shown in the Algorithmic Mirages program of the Vilnius Short Film Festival dedicated to AI presents the avatar of Nikita, whom the author decided to teach a backflip. More specifically, to make the avatar try until it succeeds. After all, for a real person made of flesh and bones, such a trick is very dangerous – you can easily break your neck. And you need a lot of attempts with moments of rest in between.

Nikita’s avatar was training on a 6-core processor with the help of machine learning. It performed more than 8000 jumps daily and finally mastered this trick. Time was saved, and the goal was achieved, albeit not the main one. Although Nikita still can’t do a backflip, he has created a great film that travels worldwide and tickles the viewers’ brains. It is clear that Nikita is more talented in the field of filmmaking than in acrobatics. So maybe it is all about measured expectations and a sober assessment of one’s abilites.

Visual arts, photography, and animation are at the vanguard in terms of their friendship with AI. Boris Eldagsen, who won the Sony Photography Awards with his ‘fake’ photograph spoke loudly about promptography while visiting Kaunas last autumn. It is still quite a new means of expression, the mastery of which also requires various talents, including patience. To be able to formulate clearly, in detail, and in an original way the task to be performed by the AI sounds like a job for writers and journalists. We discussed with Jurgita Kapočiūtė-Dzikienė, a professor at the Faculty of Informatics of Vytautas Magnus University and a language technology specialist, what dangers, or perhaps opportunities, rapidly improving AI brings to them.

The scientist has been researching AI for almost two decades. She is the head researcher at Tilde Information Technologies, which is well-known to those who write or conduct interviews. I fed a clip of our conversation to the company’s speech encryption machine. If we had spoken in English, I would have saved time, but now I was unable to trust the computer 100 percent. The interviewee made no attempts to disagree with me.

“In order to train a model to understand colloquial language, it is necessary to collect enough data on that language. Most texts you find on the internet are written correctly. The speech databases are also very neat and dedicated to the standard language. What we are lacking the most is the speech corpus of the slang used by today’s youth. Unfortunately, no matter how well those models are trained, and how much their training algorithms improve, everything is still determined by the data that is ‘fed’ to these models. In Lithuania, not many people work with the Lithuanian language, and it is also of little relevance to foreign companies,” the researcher explains. While she agrees that there will still be a need for transcribers with a real rather than a computer’s ear, skilled at hearing what is actually being said, the professor says that current speech recognition tools can help with making at least a draft of the text.

Spending time on TikTok or reels, it is easy to spot that the English content often comes with a computer voice-over. Compared to the abilities of actors, announcers, and reciters who have trained their voices, the quality of such videos is very poor, no meaningful nuances can be felt when listening to the recording, pauses and other favourite elements of a spoiled ear are missing. Similarly, on websites that offer articles to be heard rather than read, the information is simply flattened. Of course, things are a bit different and even dangerous when it comes to English and other more popular languages. It is quite easy, having a recorded sample of a person’s speech, to clone their voice and use it for criminal purposes.

However, it is also not difficult to catch such fraudsters, because they overlook some things. “When writing, we really like to shorten words. We write numbers using figures, use acronyms, insert English words, and make grammatical errors. Text-to-speech tool reads what it perceives; it doesn’t know what the case of the number should be, so it usually chooses the nominative. If words from other languages are inserted and not spelled according to Lithuanian spelling rules, we will also likely hear them pronounced incorrectly,” the professor warns us. Therefore, the text needs to be edited accordingly before turning it into speech. So, thinking about well-written and edited audiobooks, AI models speaking in Lithuanian would allow this market to grow.

Last May, it was announced that the consortium led by the Lithuanian applied artificial intelligence company AAI Labs won the competition of Eurostars – an international program, which finances the development of innovative products and services in the international market. “The company aims to develop an artificial intelligence-driven audiobook creation system where publishers and authors will be able to synthesize texts at an affordable price while maintaining the highest quality of the narrator’s voice,” the press release promises. Head of AAI Labs Prof. Dr. Aistis Raudys also states that the breakthrough in the field of natural language processing already allows artificial intelligence models to be trained in such a way that their synthesized voice would be equal to the quality of an actual human voice, “We believe that this will allow more people to read while listening and will popularize the literature of smaller publishers and authors.”

Another innovation is the creation of audio guides with the help of AI. Lithuanian startup Wisit focuses on the international market, but first, the prototype was tested in the branch of the Lithuanian National Museum in Gediminas Tower. Duke Gediminas and other characters – including the Iron Wolf – speak in AI-generated voices in this guide.

AI is also said to have contributed to creating the audio guide script. “Writing the audio guide script using Chat GPT 4 and Claude was like a game of ping pong between me and these AI apps, where the scenes kept improving with each serve of the ball. The writing of such a script is particular as the accuracy of facts must be combined with creativity; AI was perfect for this,” Simonas Mozūra, co-founder and creative director of Wisit, presents the product. The audio guide features nine synthetic voices generated by the Polish speech synthesis program ElevenLabs. If you are in Vilnius, make sure to try it out!

If an articulate reading of a text into a microphone is your only job, you should already start thinking about what else you can do, because your job offers might decrease in a few years. And how long will it take before a book that would not just be read by artificial intelligence but written by it, receives the Nobel Prize for Literature? “The current technology, which was born in 1964, when neural networks were invented, cannot yet go beyond its limits. If a certain novel or text by a specific author were not included in the model, then the model would never be able to write in the style of that author. Hence, AI is only as creative as the data it contains. Of course, when it contains hundreds of thousands of those authors and books, it is only natural that a person has not read them all and it may appear to them that AI wrote something extremely unique and creative,” Jurgita Kapočiūtė-Dzikienė points out.

“If you’re a real creator who wants to stand out, whatever has already been written probably won’t be enough for you,” the professor briefly but effectively reassures writers who are afraid of AI. According to her, AI won’t win the Nobel Prize in Literature until someone wins the Nobel for inventing a neural network or some other method that would make it possible to create an AI model capable of more than just synthesizing the data seen in its training. Thus, the limitations of current AI tools are the safeguards that ensure that the machine will not triumph over a human being.

Of course, if your work includes descriptions of services and products, adaptations of texts for various channels, and the like, it is better to think about more reliable activities, because this can be easily automated, and the free version of Chat GPT is sufficient for this. The professor suggests the skeptics, who don’t want to ‘feed’ these tools, to not write the existing ones off. According to the researcher, ideas often come not when working directly, but when we re-direct our thoughts, when we enter a new situation or take a walk in nature or a new city, “Creativity does not necessarily come from knowledge. When general intelligence is invented – the one which includes not only textual but also visual and audio information, and can communicate and accumulate life experiences, maybe even understand human emotions – then a basis for machine creativity will appear. Of course, I cannot say how it will happen. For now, these are just philosophical questions.”

Although lifelong learning is healthy in many ways, retraining can be a difficult process. Therefore, it is important to make a far-sighted decision when choosing what to study. I wonder what students J. Kapočiūtė-Dzikienė meets at VMU. Are they prepared for an uncertain future? What skills do young people need to have so they can prepare for today’s labor market?

“I consider the grading system to be the main problem,” the scientist opens up. According to her, nothing good will happen as long as high school or university students will study for grades. In fact, nothing has changed. Back in the day, students used to print out abstracts in microscopic font and stick them in their sleeves and now they call on AI for help. Of course, even such large mechanisms as universities change. Slowly. Yet some decisions have to be made here and now. For example, Chat GPT appeared in the middle of the semester, so professors had to change the rules for using the Internet.

“You need to develop your curiosity instead of trying to get a good grade,” my interlocutor aptly observes, suggesting that you pay attention not to certain specialties but to the ability to change, improve, and learn. Punctuality and dutifulness are also important. I am sure you will agree that these are more qualities than skills, but they allow you to achieve more in life.

“Knowledge can be easily accessed now, we can get an answer to a complex question very quickly,” J. Kapočiūtė-Dzikienė reassures those who are afraid that they will no longer have time to learn something. Even in a dire confrontation with AI, the best move a person can muster is not perfection but creativity. A creative person will estimate how many hours they would need to learn how to do a backflip, and then decide if they really need that.