The last time I visited the building numbered 55 on Laisvės Avenue, was three years ago, when the historic Pienocentras palace was being prepared for its new owners. Previously, it was occupied by KTU students, but now it is home to the community of Herojus School. Upon entering I was surrounded by youthful commotion: children running down the stairs, rushing to class, rummaging through their lockers, music and conversations coming from the classrooms.

As I climbed to the fifth floor to meet the school’s founders, Dovilė and Andrius Pelegrimas, I had time to reminisce about my own school. Years later, after forgetting the Pythagorean theorem, amoebas, and conductors, we still remember our favorite teacher or a bench mate because school is not only a building but also a feeling, a connection, a community. These values are certainly important for Herojus. The private school has been operating for nine years. In 2022, at the beginning of the large-scale military invasion of Ukraine, Heroiam Slava, a school for Ukrainian children, was founded and has become an integral part of Herojus.

How would you describe the students and the community of Herojus School?

Dovilė: I didn’t think the school would be so big; it has grown very quickly. It’s a life project based on a deep conviction that we can make a difference in the education system. We want to leave a colorful imprint on the heart of the pupil and the teacher’s career. Our goal is for students and teachers to discover their strengths, to put down roots here, and to feel good about coming and working here. I am a teacher of literature myself and I never call teaching a job – it is my life.

We are looking for people with ideas who don’t necessarily have a pedagogical education – I know that you can get a degree later. We have teachers who came here after 10-20 years of doing very different things because they felt they wanted to share their knowledge.

And why did you name the school Herojus?

Andrius: Dovilė came up with the name, and I remember we were sitting on the sofa, as we are now, discussing it. Hero is a set of principles, and teachers and students are encouraged to follow these principles. When dealing with people, we often miss the miraculous simple things like being at the agreed place at the agreed time, keeping your word, and if you should compete then first and foremost, you should do that with yourself, striving to do a better job than yesterday. No matter where you work, it is important to feel good where you are and to give your best. A hero’s set of principles can make a person successful no matter what he chooses to do in life.

Dovilė: Both after the founding of the school and now, I saw a lot of negativity around me and did not understand why people spread it. To me, Herojus means positivity, colors, and meaningful teaching, when you really care about what you do.

I would be curious to hear about the Heroiam Slava project.

Andrius: When the war broke out, it became clear that a lot of people from Ukraine would come to Lithuania and need help. We held a meeting with teachers and parents and decided that we would help as an organization. I thought that in such a situation it is important for a person to be safe, but it is also important to continue working and being active. It was important to ensure that the teachers were able to do what they knew and loved, so we decided to take them on, not knowing at the time exactly what they could teach. We also started looking for premises and funding, and companies and individuals contributed.

How long did it take for classes to fill up with students?

Andrius: Olga was the first teacher to come to work with us and soon the first student followed. From March to April of 2022, there were almost 100 students, in September the number reached 550 and now we have 400 and 50 teachers. We have already managed to graduate three generations of high schoolers.

Did you foresee that the need for educational assistance would last so long? Will the Ukrainian school’s activities continue?

Andrius: It worked as first aid, and we reacted immediately. Later we made other plans. Of the Ukrainians who came, the ones who stayed are those who plan to spend their lives here or at least stay a bit longer. Ukrainians have become part of Herojus, and I can hardly imagine the school without them. Now Ukrainians often move to Lithuanian classes, so the official separation and even the language barrier between schools is decreasing.

Tell us about the organization of the learning process and the daily challenges. Do you work with several school programs at the same time?

Andrius: We have an accredited Ukrainian curriculum, but since Herojus is a Lithuanian school, we want to make sure that the integrative element is not lost, so the newcomers have to get to know our country’s culture and learn the language. We have created a mixed structure. The children who come here learn Ukrainian, Lithuanian, and English – which are compulsory – the education principles of Herojus and use the same tools as all the other pupils and learn in their own language. The experiment has been largely successful, with some older children already choosing to take their exams in Lithuanian. We care about creating the conditions and the prerequisites, and it is up to the individual to choose and decide what is best for them.

Dovilė: I am also glad that there are children who are already enrolled in Lithuanian study programs, mostly studying at Vytautas Magnus University or Kaunas University of Technology. We also notice that Ukrainian children not only adapt quickly, but they are also very sociable, and proactive, and even visit us after they finish school. The Ukrainian community is very tightly knit and sometimes we get envious when we see how students visit their teachers and vice versa, that relationship is mutual, whereas it is sometimes much more difficult for us, Lithuanians, to create a relationship with our students.

Before enrolling in the school, students must go through several selection stages to ensure that their views align with those of the school community. Is the admissions process the same for the Ukrainian school?

Andrius: At the beginning we accepted everyone, but then, after a year, the principles and philosophy of the Ukrainian school became clearer, and we also introduced compulsory stages of enrollment to the school. Initially, we faced challenges – temporality, difficult circumstances, and studying both in Lithuania and remotely in Ukraine drained the children of energy, and sometimes they lacked the determination and ability to meet commitments. A year after the school was established, we agreed that the children should choose one of the learning programs.

Did you have to organize additional support within the school?

Andrius: In the beginning, we functioned more as a community rather than a school. At one point, every month we had to inform a child that something had happened to their loved ones or that their father had died. These were incredibly difficult situations. We often organized clothing drives because some teachers arrived without belongings, so we shared resources and sought help.

Dovilė: Like in all schools, we have a psychologist’s office, which the children visit frequently. After all, they didn’t come here by choice – they were forced to. Of course, we need to find a balance so they can learn to move forward and look to the future but also wouldn’t forget what has happened.

In both the Herojus and Heroiam Slava schools, you emphasize freedom, which goes hand in hand with responsibility. How do you navigate between a rigorous curriculum and the desire to give space to students’ choices?

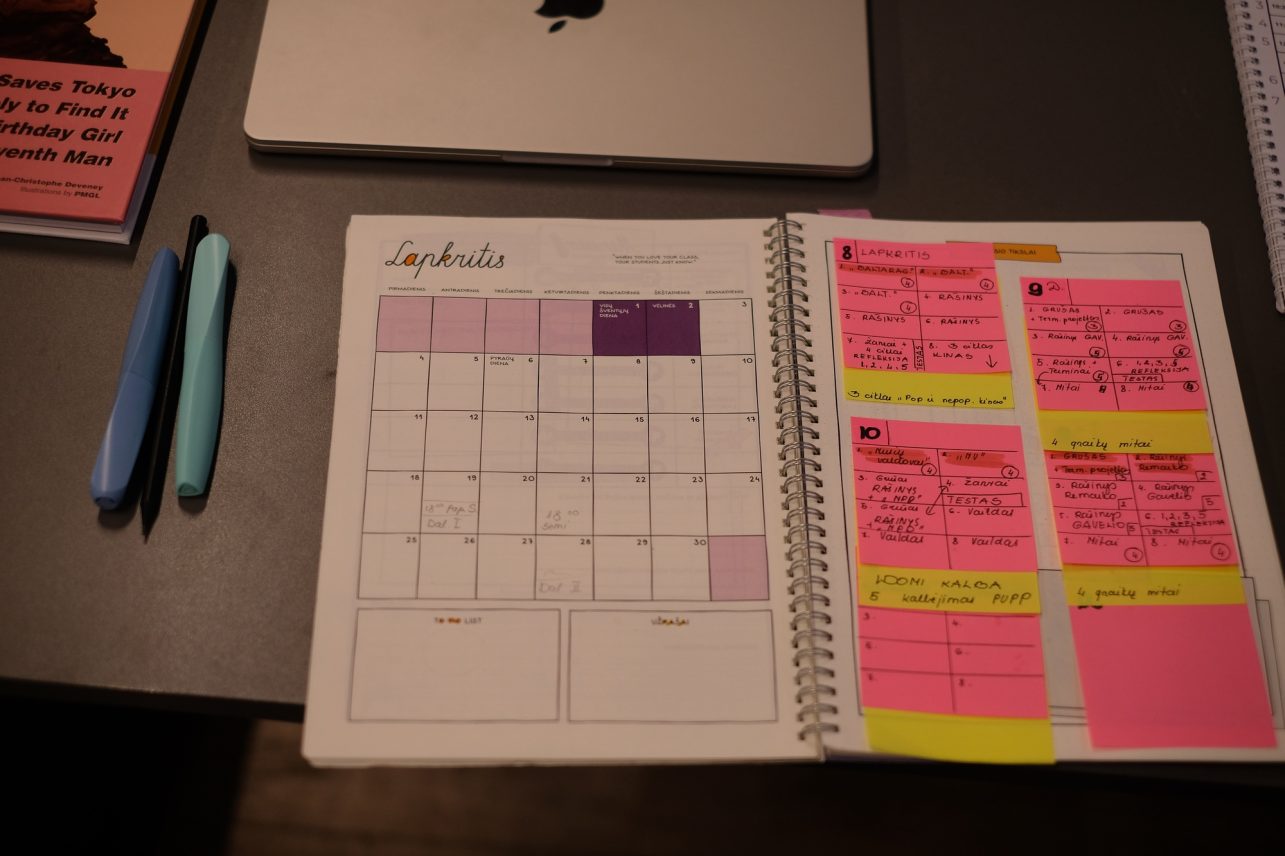

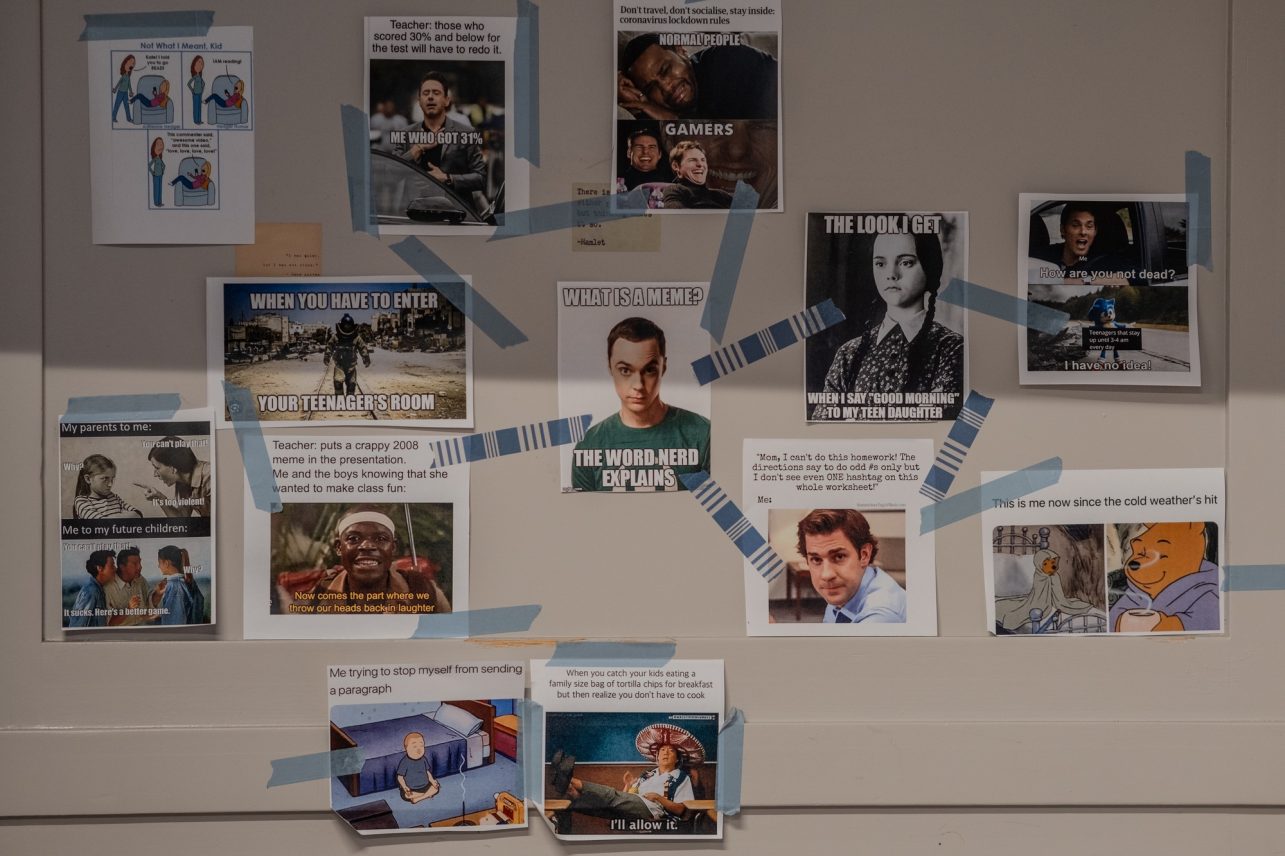

Dovilė: Students must prepare for exams according to the official program, but each educational institution can choose its own teaching methods. Let’s say you need to read the required works, but how do you do it? We read some out loud, turn others into comics because the students like it, and we don’t follow one textbook, after all, the textbook is subjective. We create our own learning materials.

The education system is constantly being reformed, with frequent changes to both programs and terms. How would you advise coping with turbulence?

Dovilė: I think teachers are used to turbulence, they always have to stay strong and make sure that they can cope; they shouldn’t blame the system for feeling lost. The teacher must try to find the right methods and help the students to learn.

Recently, your schools have expanded even more. The building on Gedimino Street, which used to house the Lithuanian printing house Spindulys, has been transformed into Herojus Progymnasium. The conversion of the building was carried out by G. Natkevičius and Partners architecture firm and their project was recognized as one of the best in Lithuanian Architecture Awards. What makes this space dear to you?

Dovilė: We’ve put a lot of work into the school, we’ve even drawn the layout of the electrical sockets in the classrooms, and we’ve laid out the meals, counted the meatballs, and worked as janitors. I really like to give new life to old things. On the ground floor, we wanted to create a community gathering place, with big windows to see what’s going on inside the school and in the city, to build a community. On the fourth floor, we have an amphitheater for events, and we want to invite people from the city to come and teach the children how to behave, say, during a play. We didn’t want the school to be associated with tall brick walls – a building you must attend, endure and only when you leave, you get to live. We want the school to be without walls. That way, young people find meaning and learn what they need both inside and outside the school. Studying in the city center has its charm because children develop entirely different skills: they must learn to cross streets safely, find green spaces, navigate public transportation, and understand that they’re running onto a street, not a schoolyard.

What would you wish for every child?

Dovilė: I would wish them to not grow up too fast and to always play in the broadest sense. I love being at school – it’s where I can always join in fun activities, whether it’s a board game or a game of dodgeball with the class. Similarly, school must not lose the core element of childhood: play. So, I wish the children to never develop a “grown-up shell”.