In September, while walking around the wagon repair workshop in Šančiai, to which the Kaunas Modern Art Foundation had briefly brought the works of the Angis group and students, I briefly thought that it would be interesting to visit the studio of Eimutis Markūnas. More specifically, I got the idea when I squatted to examine his installation Išeinantys/ Ateinantys (outgoing/incoming), trying to understand how many kilograms of flour were scattered during its creation.

The day of the meeting was sunny. It was the eve of the Hamas attacks in Israel, which escalated the war, and the sudden death of Kęstutis Lupeikis, my teacher as well as a colleague of Eimutis and a member of Angis group. The title of the aforementioned exhibition – Nerimo laikas (time of anxiety) – became a self-fulfilling prophecy overnight. But on the first bright and still warm Friday of October, we were still unaware of all that.

There was nothing behind the clinics a good three or four decades ago, and it was in such no man’s land that artists were allowed to build their studios – they were only told to cooperate with each other. The government even gave interest-free loans. An architect designed a six-meter-high ceiling for Eimutis: stained glass artist, after all. “At four meters, I told the builders: stop, that will be enough.” While construction was underway, the artist continued to work in a rented studio on Šiaulių Street. In the house that was turned into the Amerika Hotel in a movie.

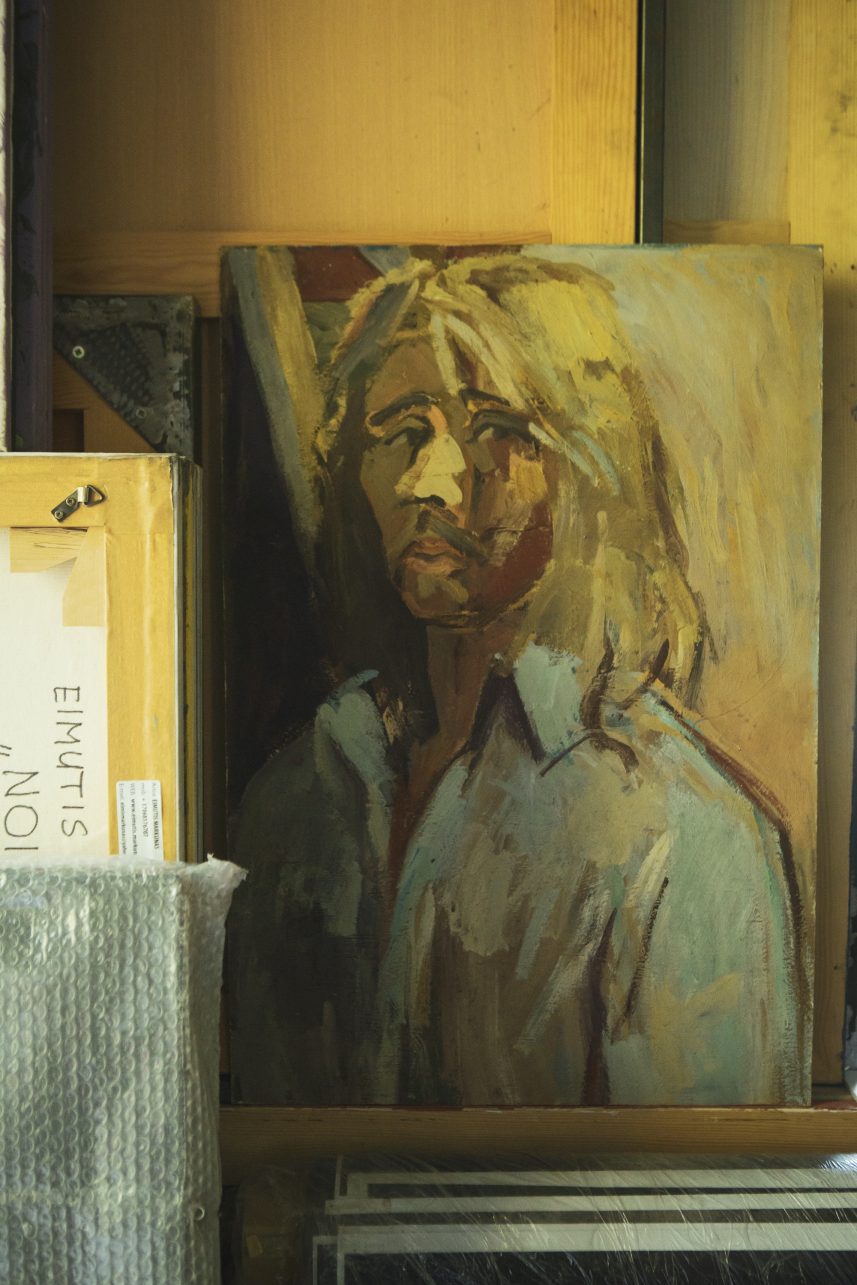

There is an easel in the studio, bought during the university years. The walls are layered with exhibition posters and small-format artworks. One of them is pink – Mattise-like, according to the owner – and dates back to when he was studying at the four-year children’s art school. The fifth grader was brought to it by his parents because his grade book contained complaints about Eimutis’ behaviour. After the eighth grade, he took the Kaunas College of Art entrance exams. Although he studied glass art in college, he had already started painting and even holding exhibitions with his buddies (like Jonas Gasiūnas), “We got together in a pack, like wolves, and started painting.” It was almost two decades before the emergence of Angis group. The heads of the college did not care much about students’ painting activities, although they did worry that youngsters had too much free time.

“That journey started in the fifth grade and still continues,” the artist calculates. He is one of those artists who cannot be squeezed into one category, and he would refuse if anyone tried. Painting always was and still is, and glass art mutated into stained glass. Although Eimutis wanted to switch to painting after two courses at the institute, Povilas Ričardas Vaitiekūnas stopped him by saying, “You will have a craft and painting is not going anywhere.” By the way, the man from Kaunas entered the monumental arts program at the academy first in line, which was a bit unexpected in those times because a considerable number of places in the art academy (instutute at the time) were given to the offspring of government officials. Photography, video art, and performance art are also close to Eimutis’ heart just like aluminum sheets, OSB panels, leftover paint, and graphite.

After graduating from the academy, Eimutis returned to Kaunas, although there was a worry that he would be appointed to work in a new art school in Mažeikiai. However, his wife Liucija had graduated from her photography program and was working in Kaunas, so the young family was not separated in the end. Not wishing to serve in the Soviet army, the young man got a job at a school in Kačerginė where he taught technical drawing to children (including Romas Zamolskis). But that was only one day a week. On other days he would be rushing to the Amerika Hotel. The teacher’s salary was symbolic, but then he started receiving commissions for stained glass works. The works of this author could – or still can – be found at Zokniai airport, in a bank in Marijampolė, at the former Jiesia factory, and now at a printing house and Jesuit high school in Kaunas as well as in churches located in Zarasai and Ežerėlis. The piece in Šilutė is no longer there but it was really appreciated by German tourists who then invited the Lithuanian artist to create a stained-glass composition for the church in Emmerich, Germany.

Before starting with the colors, we first found out a little more about the installation I was looking at before. White flour is trampled in it by black rubber boots, which, as if ordered by someone, all look in one direction. In 2006, when the installation was installed in the Kaunas meat factory for the first time, it seemed that they were leaving for good. Outgoing/Incoming was also showcased in Dresden, in the same slaughterhouses described by Kurt Vonnegut, who served there. It was also exhibited in in Katowice and the South of France, where it opened on May 9.

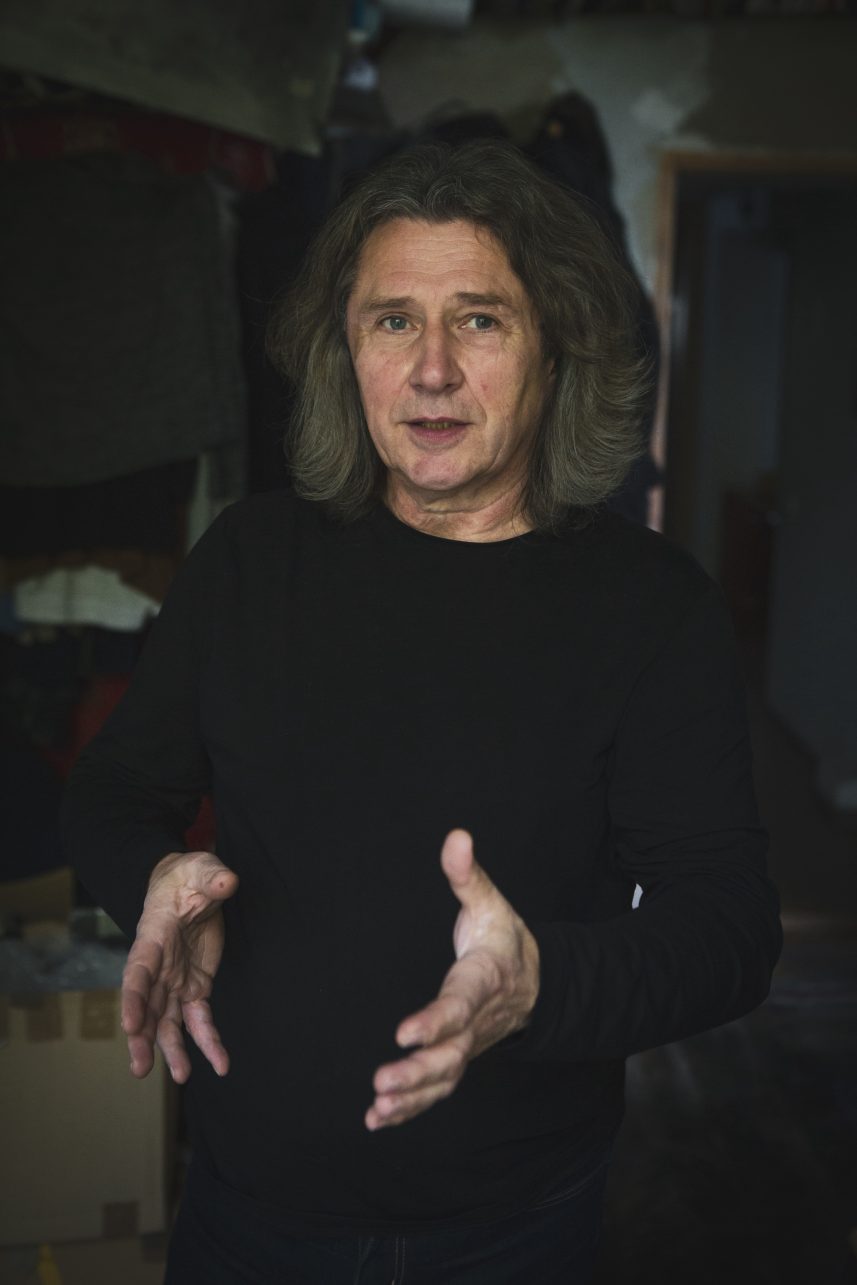

“I used to be more colorful. And now everything is black and white,” Eimutis smiles. However, I can see different colored paint buckets under the table. Purple is indeed an interesting choice. Here we remember the City Color Code campaign. In 2019, you could see the works he painted during it together with the works of photographer Remigijus Treigys in the Kaunas Photography Gallery. The essential role here is played by building supply store paint departments, where it is possible to purchase mixed paints in shades that customers did not like for various reasons.

“If it wasn’t for me, such paint would be discarded, and I use it for my work. At the same time, you express yourself and utilize the paint. They are cheaper, but it is also a kind of research: what colors do the people of Kaunas choose, and what makes them tick now? The palette from which I could choose speaks for itself,” the artist explains, adding that he has not yet put the full stop in this project, as in all the others. And then he invited me to look at the rolled aluminum sheets that had just arrived from Barcelona.

This part of the story also has to do with building supply stores. Imagine, it is raining, and your new studio does not have a roof yet. “They told me: you’re silly, fix the roof, but I couldn’t, I had to paint on that aluminum, and I did it in Šiaulių Street. Later, the roof appeared but some tinplate was left. And it all started with graters. I used to buy these tiny ones near the station, with a wooden frame, I just liked the material. The paint would drip, and I had to fight that. And then it was necessary to increase the formats, so I noticed aluminum sheets in the store. You were able to see my work on tinplate in Šančiai. The guys then said that the paint would wear off, but it is already three decades old.”

“And how did black take over you,” I ask.

“I looked for all kinds of options. I have invented a unique technology: I create with graphite. I painted enough and I got bored repeating myself or looking for something that I will never find. A new material, a new experience, a new way of thinking also brings an ideological charge.” Eimutis emphasizes that graphite is not black. It is grey, with a silvery glow, you can even see shades of pink. The blackness of the city, lingering in the paintings, is both chaos and the characters emerging from it that you have or haven’t met, seen, or perhaps dreamt.

When asked if he feels like a member of the Kaunas artists’ community, he shakes his head. “I’ve already drifted off. They are there in Šančiai, and the gallery is now in Drobė, you have to climb to the third floor, and drag your works with you,” he smiles, remembering that he never took part in the recent exhibition exploring black and white colors. When asked if solo exhibitions are more important, he says he doesn’t know what is important anymore. But then assures that, for example, sending works to Germany, from where they never return, is more meaningful and fun than taking them to a local gallery and bringing them back.

The long pauses are filled with Brian Eno’s crystal-clear music. Behind the painter, I can see a vinyl shelf. We found out that we frequent the same record store on Kęstučio Street. Eimutis’ latest purchase is a Sigur Rós album.

It is interesting how such an individualist has been engaged in pedagogical work for forty years. “It’s about something else,” Kaunas artist, who works in A. Martinaitis Art School and Vilnius Art Academy Kaunas Faculty, explains. He emphasizes that he has never treated his students as soldiers in a boot camp, although that requires energy and costs him some health. Still, it’s important to distract yourself, why would you spend all the time in the studio? But perhaps it also keeps one young. “Maybe! We are like vampires…”

So, what is the generation of artists educated by Eimutis Markūnas and his colleagues (many members of the Angis group have worked or are still engaged in pedagogical work) like? “They are talented. Although there were and are all kinds of students, I don’t want to attempt to define them. The most important thing is to teach them to be artists, to see what they want to see and do what they want to do instead of following someone. It was different back when I was growing up. Communication with professors was very formal. The way we play now was unimaginable back then. It was impossible to get into the same exhibition. Of course, when you don’t keep a healthy distance from the teacher, you get copy paste and that’s a problem. There are quite a few artists like that. I also ran from my teacher Algimantas Stoškus because many people would refer to me as “Stoškus’ student…” I deliberately tried to get out from under that hand and follow other paths,” the artist says and adds that you need to be as honest as possible.

“I don’t have any plans, but I need to work,” the artist answers my question about what he will do in the near future. But then, remembering something, he invites me to Kaunas State Philharmonic. He will perform here on November 9 with drummer Arvydas Joffe. The audiovisual performance Silence and Noise is an interdisciplinary project that includes the opposition and interaction of sound and painting improvisation” the abstract reads.

Next year on July 30, I will have my retrospective exhibition in Vilnius Town Hall. That’s the “I have no plans” for you. My monograph is on the way. I also have to wait for the Lithuanian Council for Culture’s decision.

“But I don’t want to produce too many things anymore. The world has become dreary enough from too much of everything. What is the point when you work out of inertia, out of selfishness, because you absolutely need to? What is the point of it? I can only understand the maximalism of youth. I catch myself thinking that I should do less but better,” Eimutis continues with the thought as we walk down.

There is another – stained glass – workshop in the basement. It contains a lot of everything: a spot for a craftsman, who visits Eimutis, a space for installations and wife’s projects, assembly tables, a stove called a Mercedes. Stacked against the wall are car hoods found in a nearby paint shop, which have also been painted on.

Color samples are propped up against the window. The artist makes the whole color chart – except the color red – based on lead crystal. “You put color on colorless glass and that’s it.” Sounds easy, like putting butter on toast, but after a few minutes, professional slang fills my ears, and I don’t understand anything. One of the latest creations born here is a stained-glass object, the gate for the Church of the Blessed Sacrament, which has not yet been seen because the church is still being renovated.

When seeing me out, Eimutis laughs that his hair grows so well because of the lead in the workshop. “Eat a spoonful of cobalt every day, and your hair will grow too.” Although, of course, there are special respirators, some dust still gets through them, especially when you have to work with one piece of stained glass for months. When you taste sweetness in your mouth, it means that the dose of glaze is already in your body. They say that the younger generation of stained-glass artists is leaning toward lead-free glazes and other less dangerous things. But Eimutis uses his own – maybe a tad medieval – technology. He even has a card index where everything is written down in detail, how to prepare the desired shade, just like in a pharmacy.

Coming back to the hairstyle, in fact, in all the photographs that I have seen, Eimutis Markūnas has long hair. When Kalanta self-immolated in May 1972, students were told in the art school to not attend the protests but, of course, the opposite happened. A much larger opponent that Eimutis faced there threw at him, “Oh you, Beatle…” And after this confrontation, the fifth grader said to himself that as long as his hair grows, he won’t cut it.