“And what can I do alone, as one person? Nothing,” some of the people, whose beliefs, values, and aspirations do not coincide with the general opinion, think. It isn’t easy to calculate how many people think like this, precisely because complex dialogues with one’s conscience do not reach the outside world. And we always have excuses for that.

It’s difficult to speak out loud, let alone act, when your career, family’s well-being, and relationships with friends are at stake. Polish director Agnieszka Holland skillfully portrays such an internal conflict spilling out despite everything. And you don’t even need a film for that, we have Sienos grupė (border group), which is under a lot of pressure because they simply want to help people stay human.

Arkadijus Vinokuras is similar in that respect. The last Kaunas hippie to have his locks forcibly cut, who walked around Laisvės Avenue barefoot, sweeping its dust with his flair pants made from curtains, can be found standing at the capital’s Cathedral Square every Monday since the early spring of 2022. He stands against the war in Ukraine and now also for Israel. He hadn’t lived there for long but managed to serve in the army.

Arkadijus’ father also lived in Israel, however, only for a few months, because he soon passed away. His family sent him away from Kaunas, work-out from alcohol. The entire family of Vinokuras the elder, died during the Holocaust. He was transported to Dachau from the Kaunas ghetto but eventually returned to his hometown where he created a family, but the trauma he experienced never left his poisoned body and soul. Scientists are vocal about the fact that untreated trauma is transmitted from generation to generation. Observing Arkadijus, hearing his voice, and seeing the look in his eye, it seems that he has found a cure. Maybe it is the power of art – movement, freedom, and self-expression – which no one could limit.

“My father worked as a stableman. We lived on the ground floor of a building on Nemuno Street, a family of five in one room. The horse used to stick its head through the window while we were eating, looking for treats,” my interviewee smiles, briefly immersed in childhood memories. These beautiful details from Kaunas of the 1960s are reminiscent of Markas Zingeris’ novel Aplink fontaną, arba Mažasis Paryžius (Around the Fountain, or Little Paris). And indeed, the two were friends.

Protest is a natural state

We met at the Martynas Mažvydas National Library. Returning after several decades spent in Sweden where Arkadijus’ first wife was from, he managed to work as a military attaché of the newly independent Lithuania and become one of the creators of our army. At the time he was not impressed by the then-gray, industrialized Kaunas and chose to settle in the capital. “How could I not come back? I have waited for that for so many years,” the self-described Lithuanian of Jewish origin is surprised when asked why he didn’t stay in Sweden.

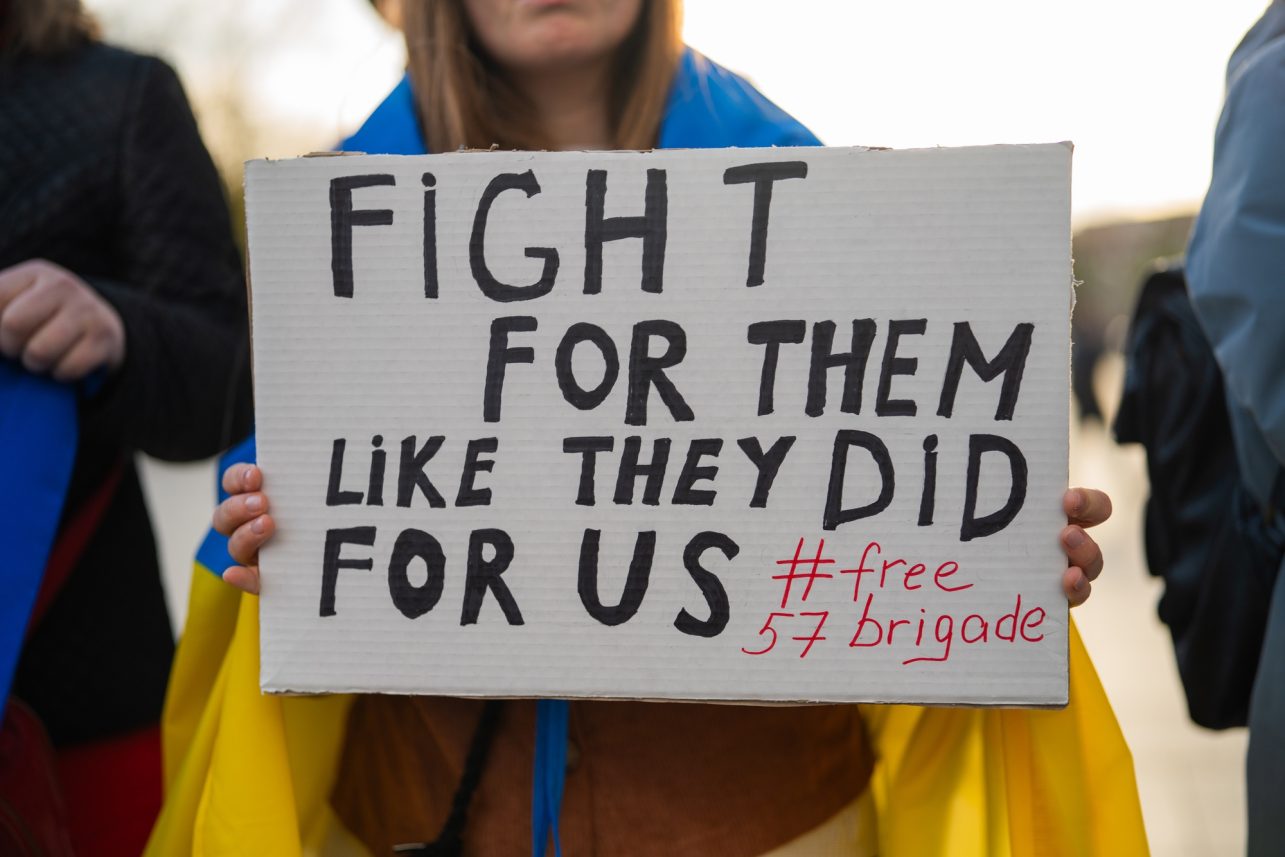

When I joined the 93rd Monday protest on April 15, Arkadijus, of course, was not alone: a few dozen Ukrainians, a handful of Jews, maybe some Belarusians, and a few Lithuanian politicians were not frightened by the gusty wind roaring in the square. However, this person’s position – to disagree with injustice – is primarily a personal, and therefore quite lonely, decision, hence the title of the article. Also, he was completely alone at the Royal Swedish Opera in 1988 when, after performing in Verdi’s Rigoletto and returning to the stage to take a bow, he pulled out a poster with the letters U, S, S, and R made of chains.

The message was addressed to then Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR Nikolay Ryzhkov and his entourage. A former – or maybe a permanent – member of the Kaunas hippie community called Company told the director before the show that he did not want and could not act for such a person when his friends were imprisoned or kept in psychiatric hospitals, however, he was still forced to go on stage. Those people could not protest, so Arkadijus embodied the voices of dozens, maybe even hundreds of people with his stance. True, it cost him his job, but strong Swedish trade unions later helped him fight for compensation.

Even before this event, when perestroika began, Arkadijus had already become a member of the Swedish press community. One newspaper simply contacted him – a known actor, who traveled a lot around Sweden and was always loud about the situation in Lithuania. After the newspaper, television, and radio followed.

Now we can return to the Nemuno Street of the ‘60s, where, like elsewhere in Kaunas, Radio Luxembourg and Voice of America were being listened to in secret. “I knew we were occupied when I was kid,” Arkadijus says, and soon his eyes light up as he remembers the feeling he got when he first heard Deep Purple and Led Zeppelin. Common interests brought him and other future members of the Company to the City Garden, where Modris Tenisonas, who moved to Kaunas, noticed the youth. After auditioning for Tenisonas Arkadijus became a mime and, subsequently, an actor and a circus performer. Also, as I already mentioned, a journalist and even a taxi driver. This is the name of his autobiography: Taksi Kristaus išpažintis (Taxi Christ’s Confession). The actor tried this craft in 2019 after returning from Ukraine, where he worked with children affected by the war as a drama teacher. There are many ways to show your position and stay true to yourself.

Torn away from the community

One of the reasons for dialing Arkadijus’ phone number is the 52nd anniversary of the self-immolation of Roman Kalanta commemorated in May. Recently, I got my hands on VU researcher Egidija Ramanauskaitė’s new book Kauno hipiai (Kaunas Hippies), which, based on the events of that time and the testimonies of their participants, describes the atmosphere in Kaunas before and after the fateful May 14 in 1972. Arkadijus is one of the respondents. He emphasized the year 1970 for both the author of the book and me, when the Company went to Tallinn to visit like-minded people. The KGB was particularly interested in this trip and in the personalities, connections, and ideas of these young people in general.

Although I have heard a lot of testimonies from that time, what my interviewee told me while calmly drinking his coffee with milk, shocked me. Over several years, he had been a frequent guest in the occupiers’ offices, spent time in jail, and suffered torture and psychiatric experiments more than once. Finally, he received an offer to get out of sight: move to Israel (from there he soon moved to Sweden). Around the same time, Tomas Venclova and Aleksandras Štromas also left Lithuania. A question remains: how was it possible to simply emigrate from a completely closed-off Lithuania to a free country? Perhaps the occupiers thought such activists would do less harm when they were conveniently located in the West.

So, what was Arkadijus doing when Kalanta self-immolated? “Neither I nor the others knew Romas. I don’t know how he appeared at the City Garden,” the Kaunas-born actor claims. However, he and other members of the Company definitely knew about Jan Palach, who self-immolated in Prague some years ago. The emotion that swept across Europe defied curtains and walls, and the united forces of music and art helped to maintain the strong signal.

Arkadijus arrived at the scene when the body was already being taken away, which was a bit later than Tenisonas, who managed to throw a jacket over the young man who had turned into a torch. It didn’t take long for Arkadijus to be caught by the police – it turns out that two female minors had run away from home. The company shunned friendships with younger girls, partly to avoid harassment from the officers. He had to fly to Tallinn, where, it was said, the teenage girls went. They were indeed found in Tallinn, but no one allowed the hippie to return home with them. He was told to wait until they sent money for his ticket. KGB people stopped him at the airport. “Are you in a rush to get to the protest?” they asked. “What protest? I don’t know anything…” he answered. It might seem strange now. What took place in the spring of 1972 in Kaunas, today would definitely be broadcast on Facebook and TikTok. At that time, Arkadijus really did not know anything and, of course, did not participate in the main protests.

The rest is history. Modris Tenisonas pantomime theatre was closed. The activities of music groups and freedom of expression were restricted. The spirits were low, but people wanted and needed to act. After all, they were so young. A year later, on the first anniversary of Kalanta’s death, Arkadijus found himself in a military hospital in Šančiai, of course, in the psychiatric ward. A little later, at the age of 22, he entered the Juozas Gruodis Conservatory. There was simply no other choice. However, studies were not the main occupation – helping those who sought to avoid service in the Soviet army was. The young people’s methods were impressive, they gave a bump on the forehead to the son of some important Ukrainian offcial, gave him drugs to make him foam at the mouth, left him on the Vokiečių Street in the capital, and called an ambulance. Such exploits could cost years in prison. But it all ended with Israel, and then Sweden.

The Monday meetings that Arkadijus invites to actually started in Stockholm. It was in 1990 when Lithuania was destroying the Soviet Union from within. People from other Baltic countries also participated in them and Arkadijus would always end the gatherings with poetry. Back then he counted 79 meetings. Now, the number is sadder. But he must stand because those, on whose behalf he stands, cannot do it themselves.