When the Soviet Union occupied Lithuania, Lithuanians, as well as other nations, were deported en masse to the farthest corners of the USSR. This was a planned and purposeful activity to control and exclude certain social groups from society.

Deportees often faced hardships due to extreme climatic conditions, insufficient food, backbreaking physical labour and social isolation. Many of them lived for years in conditions so harsh that it is hard to imagine now. Not only adults but also children suffered the hardships of exile. Unfortunately, in exile, young children often experienced much greater difficulties than adults. Children’s lives there were exceptionally difficult: they faced the lack of food and were constantly exposed to terrible cold; every day was full of tension, all of which had long-term effects for the rest of their lives.

Yet, even in the most difficult conditions, children wanted to play. With their limited resources, they created their own games to help them overcome both tension and boredom. Their toys were objects found in nature, such as sticks, pine cones, beautiful pebbles or pieces of coloured glass. Much snow, biting cold and sledging outside were just a few little things that could lift their spirits in such difficult conditions. Playing with the sledge or just spending time with their peers were small activities, but they gave the children the joy of adventure and distracted them from the tiring daily life.

The hero of this story is the sledge. The museum staff simply call them “the sledge from exile.” It seems to be a simple and common item from our childhood. However, the sledge is not ordinary; if it could speak, one would need more than a dozen pages to write its stories.

The sledge was donated to the museum as a family relic by Danutė Trakinskaitė-Kriščiūnienė, who was born in 1957 in exile in Vorkuta, Komia ASSR. Both Danutė’s parents were freedom fighters who were convicted by the Soviet occupiers and spent the most beautiful days of their youth in exile, in labour camps. They met there and got married. Danutė’s father, Mečislovas Trakinskas, came from a family of large farmers. He had connections in the underground and helped Lithuanian partisans to obtain forged documents. In 1948, Mečislovas Trakinskas was arrested for this and sentenced to 25 years in prison. He was deported to Vorkuta, the special Rechlag camp No. 6, where Danutė’s dad worked in a coal mine. Because of the extremely hard physical work, frequent accidents during coal mining and very poor food, there were many crippled and exhausted political prisoners, some of whom died because they could not bear such conditions.

Danutė’s mother, Jadvyga Budzinauskaitė, was also deported to Vorkuta camp. She was also sentenced for helping freedom fighters. Danutė’s mother had been nicknamed Gėlelė (Little Flower), acting as a liaison for Lithuanian partisans. The entire Budzinauskai family was involved in the anti-Soviet resistance. In 1948, they were all punished for this: some were sentenced to prison in labour camps, while others were exiled to the harshest places in Siberia.

Between 1953 and 1955, strikes and uprisings spread in the special regime camps. Prisoners demanded easier living conditions. The Soviet authorities used brutal force to quell the unrest. Lithuanians took an active part in all the prisoners’ uprisings. One of the largest uprisings in Vorkuta took place between July 19, 1953 and August 1, 1953.

Although the uprisings were suppressed, the Soviet authorities were forced to implement the prisoners’ demands: the abolition of the special regime of imprisonment, the alleviation of work and life conditions and the start of reviewing the criminal cases of political prisoners and their rehabilitation.

Danutė’s mother was released from the labour camp in 1955. A year later, her father was also released. They got married. Although they were not imprisoned in the camp, they were not allowed to settle in another area for some time. In Lithuania, no one was waiting for them as well: their home was nationalised and strangers were moved there. In order to buy a flat in Lithuania, Danutė’s parents needed to earn money; therefore, they decided to stay for some time in Vorkuta, where Danutė’s childhood days passed.

Danutė remembers this period as a very bright one. Although they lived a very modest life, she has many warm memories of the time spent with her parents, the long games with the children living nearby and the occasional parcels from Lithuania. However, when she was six years old, her mother was severely burnt in an accident and died after some time. Danutė’s dad decided to bury his wife’s remains in Lithuania, where he and his family were already planning to return to in the near future. With the remains, they took all their important belongings with them to Lithuania. Among them, there was Danutė’s sledge for children.

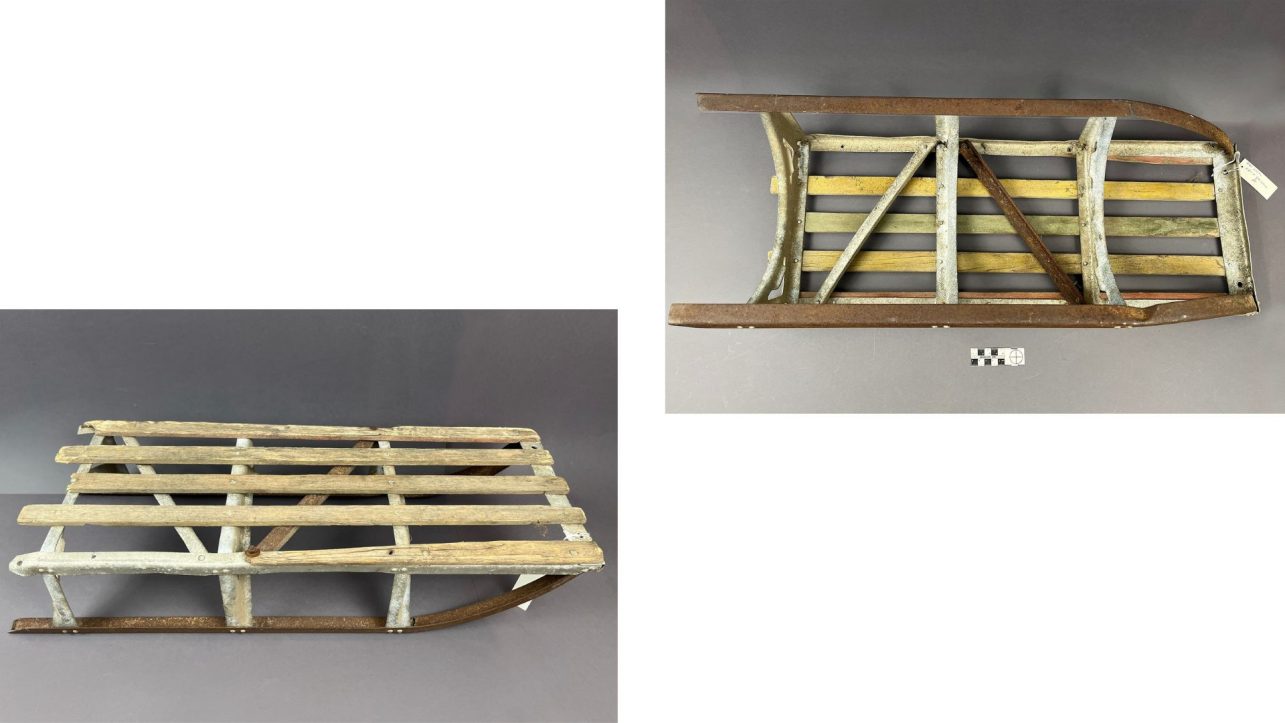

As Danutė remembers herself, the sledge accompanied her throughout her childhood. She used to play with it, and her parents used to take her to kindergarten on a snow-covered road, wrapped in a warm scarf. Being in exile, her parents always thought of their homeland, of how one day they would return there. Encouraged by his patriotic feelings, Danutė’s father painted the sledge boards with the colours of the Lithuanian tricolour – yellow, green and red. The locals did not pay much attention to it, because they did not understand what these three colours, dear to every Lithuanian, could mean. The sledge, as a family heirloom, as a memory, returned to Lithuania together with other things after all the suffering and hardships in foreign lands. This exhibit, donated by Danutė Trakinskaitė-Kriščiūnienė and brought back from Vorkuta, has enriched the collections of our museum on the exile theme.

The sledge arrived to the restorer’s workshop in satisfactory condition. The consequences of their long use were obvious. The body of the sledge is made of aluminium, and the gears are made of iron alloys. The seat is made of narrow wooden planks, on the underside of which there are remnants of three colours of paint. The upper part of the planks is covered with a layer of dirt and the paint is rubbed off. The planks exhibit signs of wear with worn edges. All the elements of the sledge are riveted together. The metal surfaces are covered with a thick layer of corrosion and dirt and deformed. In some places the joining elements are missing.

It was decided to conserve the sledge, i.e. to remove the corrosion products and accumulated dirt, to expose, reinforce and preserve the remaining paint layer, and to coat the surface with conservation materials. The exhibit was cleaned with special restoration techniques: cleaning of accumulated dirt and softening and mechanical removal of corrosion. The metal surface was smoothed and coated with restorative conservation materials. As a result, the exile exhibit has been conserved, the remaining paint layer has been preserved and the exhibit has been given an exhibition appearance.