I have often heard from visiting friends or colleagues that Žemaičių Street is like something out of a movie, completely un-Lithuanian. Indeed, as you descend toward K. Donelačio or V. Putvinskio streets, you might feel as if you’ve stepped into another country, where hills are not that exotic. At the lower part of the hill, almost directly across from the preserved authentic stairs, stands one of the street’s most notable landmarks: a lovingly restored house of Sofija Kymantaitė-Čiurlionienė, now inhabited by the fifth generation of one of the most famous names in Lithuanian history. We are visiting Džiugas Palukaitis, an employee at his great-grandfather’s namesake museum, a painter, a custodian of Sofija’s memorial room, and a guardian of historical memory.

Five generations in one house

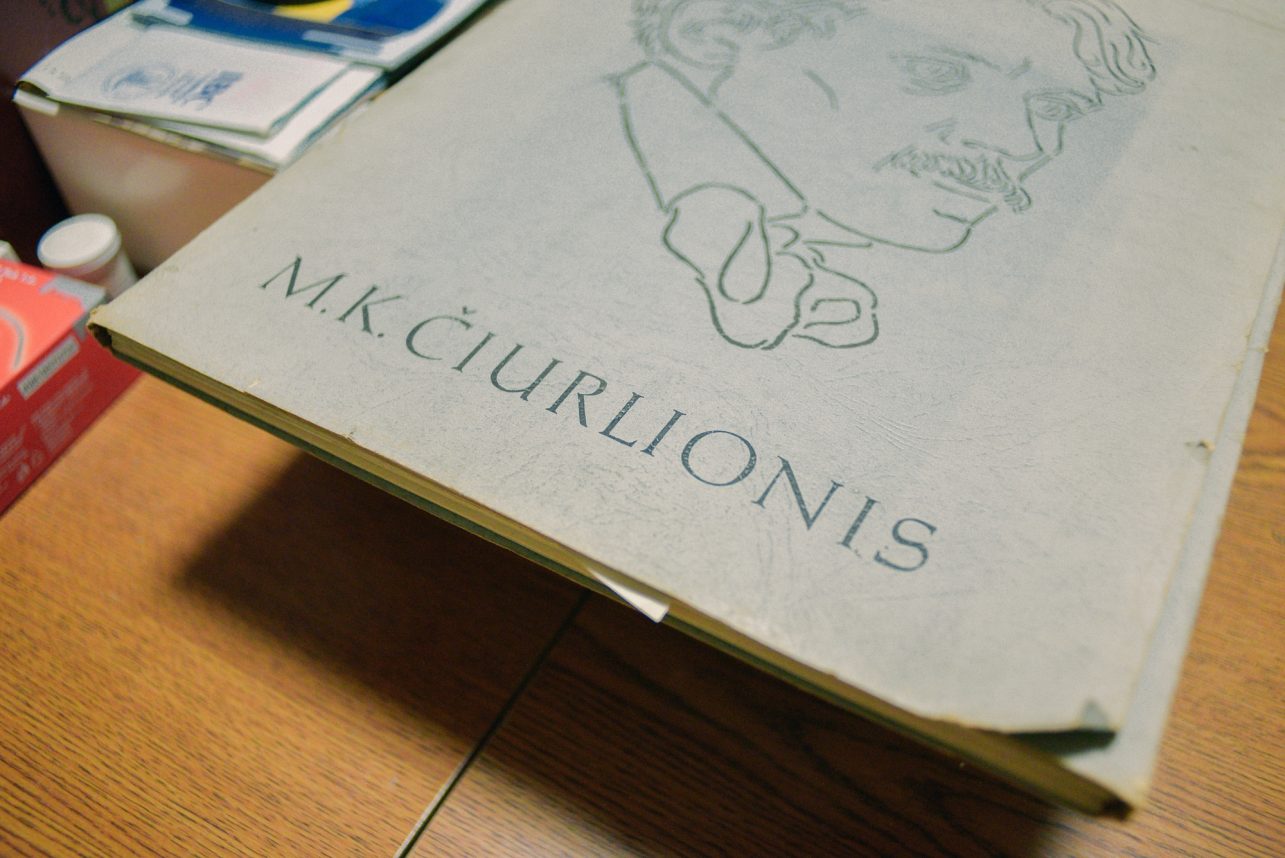

Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis and Sofija Kymantaitė married in 1909. Their shared happiness was brief – only three years passed from their first meeting until the painter’s death. During that time, they had one daughter, Danutė. She later had three children: her eldest daughter, Dalia, followed by her brother Kastytis, and about ten years later, their youngest brother, Vytautas.

“Dalia, my mother, had three sons. I am the middle one. I have two more cousins, great-grandchildren of Čiurlionis. There are five people in our generation. I am not alone, but I am currently looking after this house that my great-grandmother built. However, we reckon that not 4 but 5 generations have lived here: her mother Elžbieta moved in with Sofija when the house was finished. So, we have been looking after this house for almost a century now,” D. Palukaitis begins the story.

The house is believed to have been completed in 1933. Although an earlier date can be found on the facade, the owners say it is probably inaccurate. An old memorial plaque from Žemuogių Street, which has been preserved, states that Sofija Kymantaitė-Čiurlionienė was still living in Žaliakalnis in 1932. According to family stories, she moved here just before Easter in 1933.

The house required a lot of money

Sofija moved to Kaunas in 1911 after her husband’s death and faced professional challenges – her lack of a higher education diploma prevented her from obtaining a teaching job for some time, although she certainly didn’t lack talent. Her studies in medicine and philosophy at the University of Kraków had to be interrupted early due to the lack of funds.

“Eventually, however, Sofija started working in 1925 and taught until 1938. Her teaching work, her activities in the Scouting Society, the preparation of textbooks, and other literary and journalistic work eventually allowed her to save some money, but not enough to build the house. Other funds were used here,” Džiugas says.

The essential condition for the completion of the house project was the inherited paintings by Čiurlionis: after some negotiations, it was decided that the main heir to the works of the famous painter would be his daughter, Danutė.

“The money paid by the state for the paintings was previously deposited in a bank. When Danutė reached the age of 21, the money could be used. Sofija and Danutė’s first concern was the construction of a monument to Čiurlionis in the Rasos Cemetery in Vilnius, then still under Polish control. They commissioned the monument from J. Zikaras and had it erected in 1932. Then they started thinking about a house, but they still had to take out a loan,” says the great-grandson of Čiurlionis.

Friendship with other intellectuals

Likely, the burden of construction was somewhat eased by the fact that Sofija had long been acquainted with another famous Lithuanian intelligentsia family: the Landsbergis.

The house on Žemaičių Street was designed by Vytautas Landsbergis-Žemkalnis, who was at the height of his career at the time. At the bottom of the hill, a beautiful two-story, two-apartment house with a semi-basement and attic, with modernist features, has been built, practically unchanged to this day.

The architect’s father, Gabrielius Landsbergis-Žemkalnis, was a playwright and public figure, a distributor of banned publications. After the press ban was lifted, when the intelligentsia in Vilnius was creating Lithuanian culture, he wrote and staged plays. In 1907, he directed the play Mindaugas, which also starred Sofija Kymantaitė, who was living in Vilnius at the time, and Mykolas Šleževičius, the future Prime Minister of Lithuania.

It is said that Čiurlionis himself, who was already Sofija’s fiancé at the time, was often seen backstage. It is also known that G. Landsbergis-Žemkalnis felt great affection for Sofija and did not hide his admiration. In this environment, Sofija also knew Gabrielius’ son Vytautas from an early age, who eventually became one of Lithuania’s most famous architects.

The center for intelligentsia and Lithuanian language

Although Sofija Kymantaitė-Čiurlionienė herself did not receive a higher education diploma, her home became a meeting place for the intelligentsia, where topical issues related to the formation of the foundations of the Lithuanian language were addressed. Both art historians who have described this phenomenon and my interviewee himself refer to them as “Čiurlionienė’s Saturdays”, where linguists, translators, writers, educators, and others with an interest in our language gathered.

“The language was heavily polluted with foreign words of Polish and Russian origin. In the interwar period, after the restoration of freedom, everyone rushed to translate literature from European languages, so that people would have something to read and a window to the world would open. However, foreign literature talked about things that the Lithuanian language was not yet used to talking about, so the translations were of a very poor standard, with a lot of foreign words and jargon,” Džiugas continued.

There was a need for good, translated literature, but it had to be translated into good Lithuanian. Sofija translated from French. At home, people shared ideas, read, commented, and advised each other. There were maybe 30 people in that circle.

From gatherings and conversations, the newspaper Gimtoji kalba (native language) eventually emerged. It is still published today, but at the time, it was in particularly high demand. According to the interviewee, every civil servant had a copy of the latest issue on their desk.

“By the way, it’s worth highlighting an interesting detail: although the intelligentsia of that time often had hedonistic tendencies, such things were forbidden in this house. This reveals Sofija’s character – she was quite ascetic and highly disciplined. In her home, smoking and alcohol were not allowed. Instead, people enjoyed coffee, cookies, and pastries,” adds the interviewee.

Some notable neighbors

The house was originally planned for two apartments: one per floor. The owners always lived in the first one, and the second one was rented. This was a common practice for almost all landlords in Kaunas at that time: renting guaranteed a very good income. So, who lived on the second floor?

“The first person who comes to mind is the Russian-born Prince Vasilchikov. I think there were several generations of Vasilchikovs in Jurbarkas. However, titles meant little in Lithuania between the wars, and he worked as a lawyer. Of course, he was always short of money, and he didn’t pay the rent on time, and finally, Sofija demanded that he find a place that he could afford. She left him with the impression of a very strict woman,” Sofija’s great-grandson recalls.

After 11 years of exile, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Lithuania, diplomat and translator, Juozas Urbšys, took up residence in the semi-basement. He was friends with Sofija’s daughter, was married to Marija, the daughter of his close friends the Mašiotas, and was himself in contact with both Sofija and Danutė. Džiugas’ grandmother, Danutė, had even visited the Urbšys in the Vladimir region, where they had settled after their release from prison, but had not been allowed to return. The pretext for her visit was a book that had been requested to be translated into Lithuanian.

In addition, Lithuanian Jews were also accommodated here during the Holocaust. Sofija Čiurlionienė, Danutė Čiurlionytė-Zubovienė, and Vladimiras Zubovas were recognized as Righteous Among the Nations in 1991 and later awarded the Life Saving Cross. Danutė provided the Jews with new documents and Catholic certificates. This was done despite great danger and with two children of her own.

The Soviet occupation did not destroy the family home

S. Kymantaitė-Čiurlionienė died on 1 December 1958. During the funeral, her coffin was escorted on foot from the Kaunas Public Library on K. Donelaičio Street to the railway station, and from there people were transported by buses to the Petrašiūnai Cemetery. The procession stretched across what was then Lenin Avenue. According to the survivors, “the feeling was that the mother of all Lithuania had died.”

Sofija was known for her diplomacy, restrained demeanor, and respect for different opinions. It is said that on Saturdays, the house was a gathering place for both the left and the right: people who might not even greet each other in other places somehow came together here.

“Among the visitors were priests, Christian Democrats, and leftists. While still in opposition, Paleckis and Sniečkus knew and respected Sofija, so it is likely that this helped ease her personal situation. It is said that when the Soviets arrived, signatures were being collected from the intelligentsia to supposedly show their support for the new government. Another Kymantaitė, Kazimiera (who had the same surname but was not a relative), came and decided on her own to report that she had found no one at home. The house was nationalized, but Čiurlionienė was allowed to live there until her death,” D. Palukaitis shares stories he heard in his childhood.

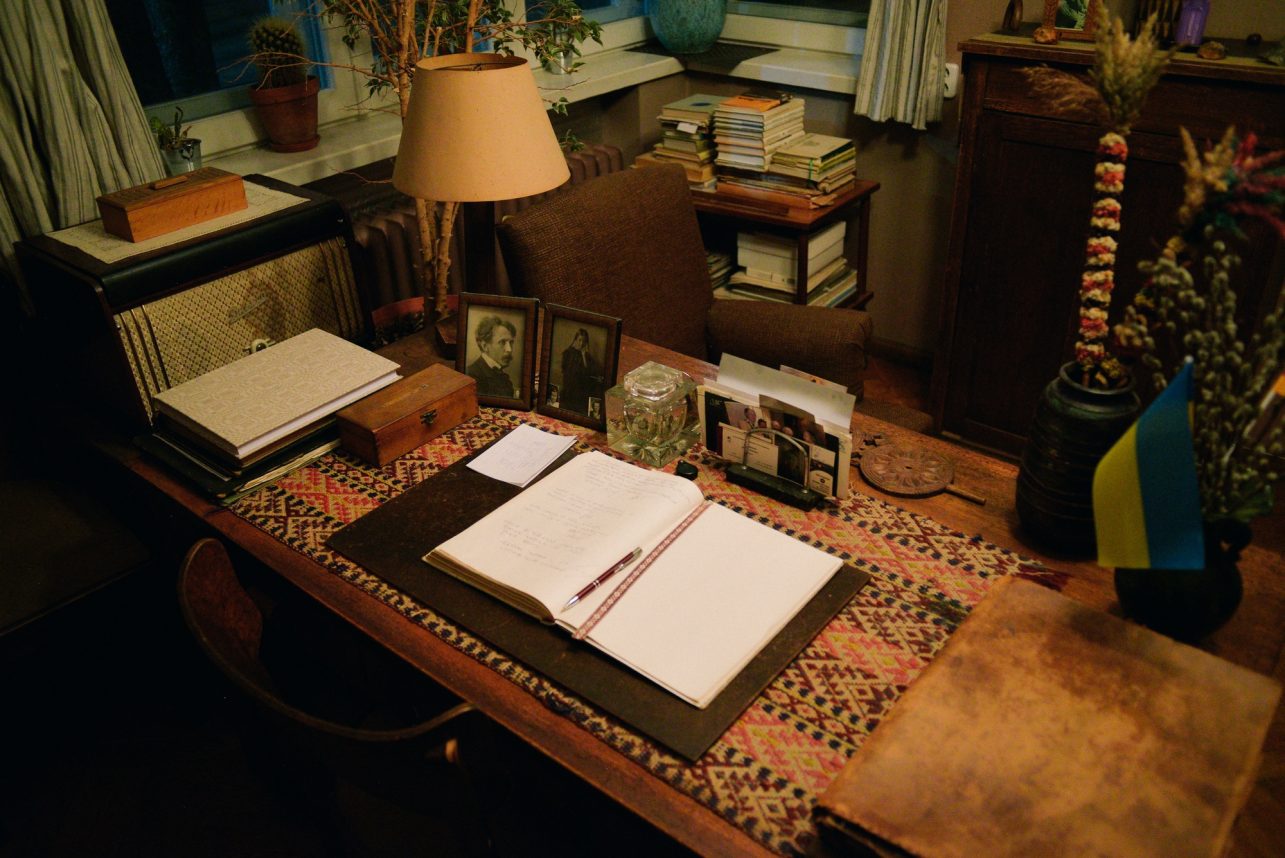

However, the house remained in the large family even after Sofija’s death. The families who lived on the second floor moved out, leaving only the greatly enlarged family in the house. Finally, in 1971, on the occasion of Sofija’s 85th birthday, the Kymantaitė-Čiurlionienė Room-Museum was opened.

There is more of the family’s legacy in the city

As Džiugas once said in an interview, “I draw or paint whatever I want and however I can.” He is not only the fourth or fifth generation of a renowned family living in the same house but also a fourth-generation artist, creator, and cultural figure. His parents were also artists: a sculptor and an architect.

According to art critics, Džiugas’ works, full of childlike naivety and playfulness, resemble book illustrations. The paintings impress with their aesthetic sensibility. However, the host mentions during our conversation that he is not a professional; he has been creating in his free time since childhood and graduated from what is now the Kaunas Art Gymnasium. I may not be an art critic, but I can see (or perhaps want to see) traits reminiscent of his great-grandfather: evident natural motifs, an earthy palette, and a sense of harmony. It feels as though everything speaks here, except for people.

Džiugas’ mother Dalia Ona Palukaitienė, who passed away in June 2023, graduated from Vilnius Academy of Arts. She was awarded the Medal of the Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas. Among her most famous surviving works today, we can see the newly restored reinforced concrete sculpture Youth in the Valley of Songs, as well as Spring on Taikos Avenue near the Vyturys school. But the interviewee says that most of her works can be found in Petrašiūnai Cemetery, decorating the graves of many famous Lithuanians.

Džiugas’ father, Reginaldas Vincentas Palukaitis, designed the Šančiai Polyclinic and the Eye Clinic in the Kaunas Clinics complex. He still lives in this house and bids us a respectful farewell before our conversation ends. Džiugas’ grandfather, Vladimiras Zubovas, was also an architect who designed the oak park, the amphitheater of the Valley of Songs, and Balys and Vanda Sruoga’s house (currently a museum). Meanwhile, his frequently mentioned grandmother, Danutė, followed in her mother Sofija’s footsteps, becoming a writer and translator. Džiugas notes that some of her translations remain relevant today, with publishers still reaching out to request their use.

Meanwhile, I am just another journalist, the child of late Soviet-era newcomers to Kaunas. As the Lithuanian saying goes, the first generation off the plow. But perhaps this only deepens my appreciation for the significance of intellectual families in shaping our nation, our state, our heritage, history, and cultural legacy. The greatest gift for me is the opportunity to witness firsthand the people and places that make Lithuania a far more fascinating country.

As for Sofija Kymantaitė-Čiurlionienė’s room-museum, it will not disappear – it remains in reliable hands, ready to share its stories with future generations. With prior arrangement, the remarkable history of this house is open to all who wish to learn about the creators of our city’s past. It is heartening to see how much this legacy means to Čiurlionis’ descendants, who, before bidding farewell, handed me the visitor’s book filled with well-known signatures to add my own.