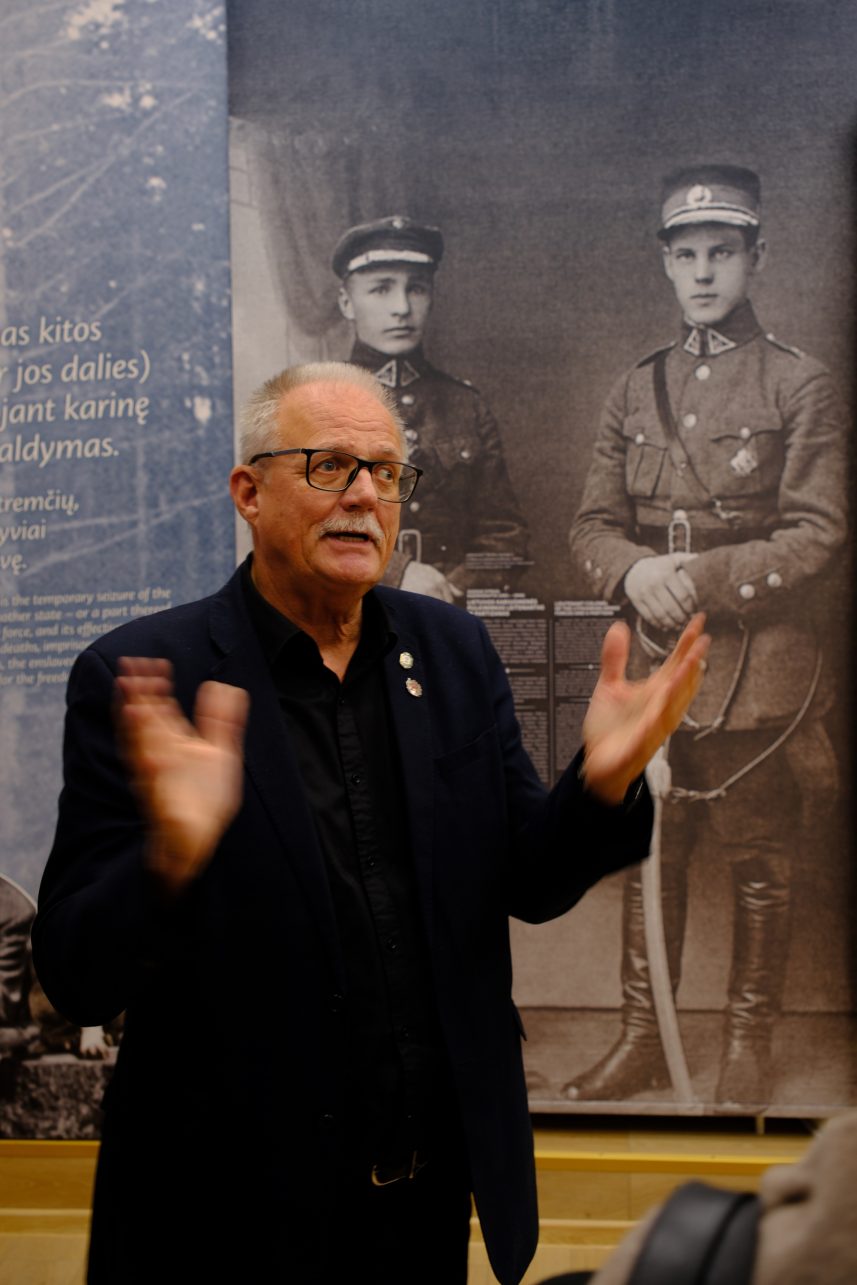

“Children come to our museum, and I tell them about my childhood in exile. Times were tough; there was no bread. I tell them: my parents leave for work and put me, a five-year-old, in line for bread. I had to wait several hours by the bakery; there was no shop there. One child asks, ‘Why didn’t you just go to Maxima?’” Vladas Sungaila shares a Marie-Antoinette-like memory, which illustrates how well we live now. He is the chairman of the board of the Lithuanian Union of Political Prisoners and Deportees (LUPPD). The museum we are standing in is a small room on the second floor of a building on Laisvės Avenue owned by the LUPPD.

Thousands of Kaunas residents pass by this building, reminiscent of the Tsarist era and the greatness of the Lithuanian army (the Officers’ Club operated here before the one next door was built) every day.

(The text “United by survival” by Kęstutis Lingys and Kotryna Lingienė was published in the January 2026 “Networks” issue of “Kaunas Full of Culture” magazine)

Admittedly, although we have looked through the windows of the union’s bookstore on the first floor many times, this was our first time inside. The museum was news to us. It partly replaces a long-defunct institution in the city’ s Old Cemetery, in an administrative building designed by the famous architect Stasys Kudokas (they say it simply did not suit the museum, and it was difficult to renovate since it is on a heritage list). But we came primarily to learn more about the activities of the LUPPD, so let’s start there.

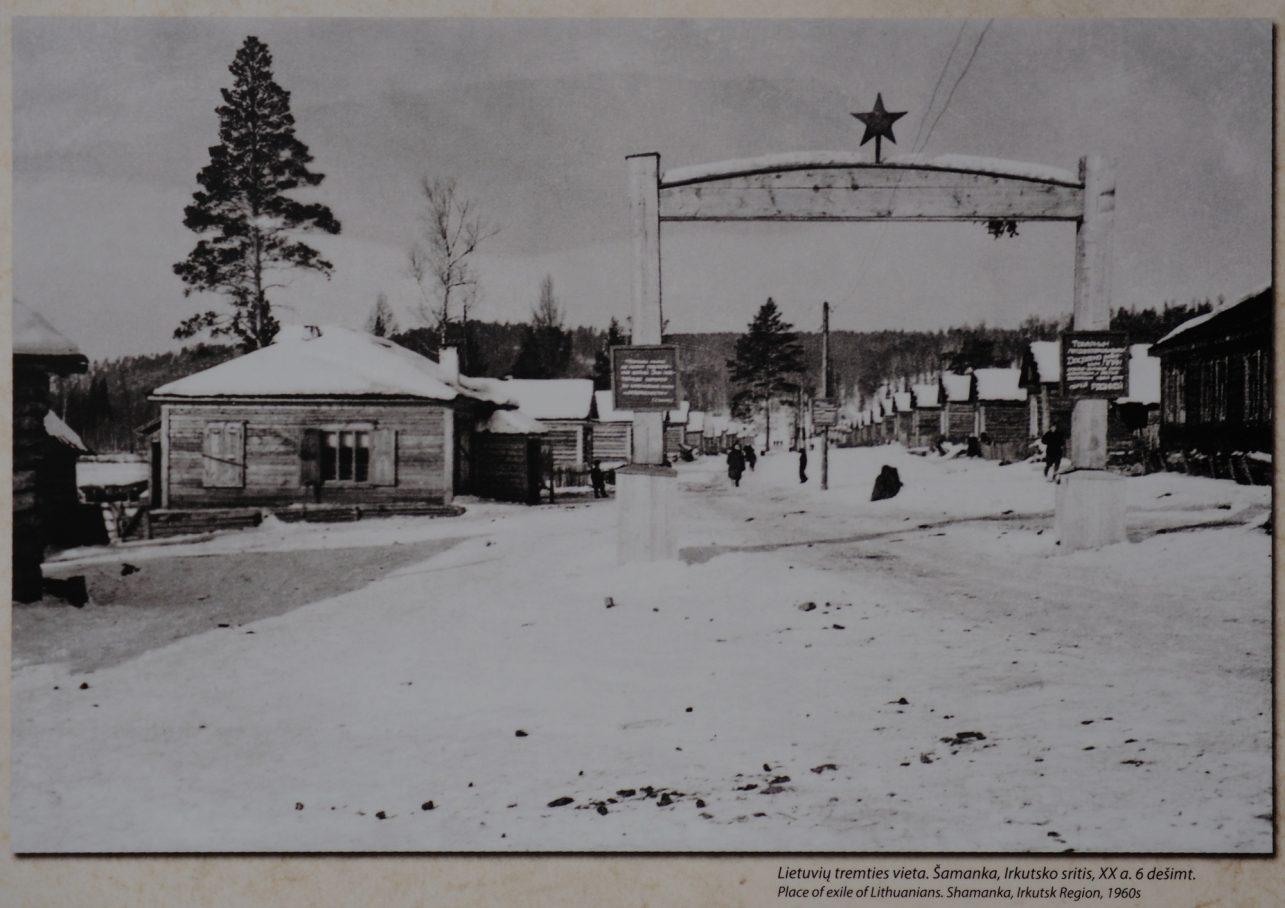

It is estimated that between 1940 and 1953, the Soviets carried out 35 series of mass deportations, forcibly removing at least 130,000 people from Lithuania. Some died during the first winter, while others started families and had children, returned only to be deported again, or perhaps never saw their homeland again. “Our ranks are thinning, even though we are one of the largest public organizations,” V. Sungaila notes. According to him, the union does not unite everyone; there’s also an association, and previously, there were separate groups of people deported to specific regions. Today, there are about 20,000 people in Lithuania with deportee status.

“Some of those who were born in exile, now seniors, have only just started sorting out their documents. After the documents are in order, they receive a pension supplement, and some also join in the activities, even though they hadn’t participated before. But it is necessary to help them, because those 20 years spent in Siberia only now start affecting their health, and it is not easy to get into a sanatorium. By the way, children and grandchildren of deportees born in Lithuania participate in the union’s activities – exhibitions, concerts, meetings, and trips – as sponsors.

How did this historic building in the center of Kaunas come to be dedicated to deportees? “I remember that in 1988, everything started to change. There was a great spiritual uplift, and you could publicly admit that you were a deportee and create your own organization, which was unthinkable before. The Exiles’ Club was founded, and it met in smaller premises. Then, when privatization started, our chairman, the signatory of the March 11 Act, Balys Gajauskas (we will celebrate his 100th anniversary on February 24, ed. note), applied for larger premises. Lithuanians in exile helped a lot – they sent money from Canada, Australia, America, and the locals also contributed, and we bought the premises. This was the Officers’ Club during the interwar period, and in Soviet times, it was some kind of military institution. Right now, we are collecting information. We want to prepare the historical description.” On the ground floor, you will find not only a bookstore, which we will visit later, but also a cafe and a shop. Rent is a significant contribution to the union’s budget. “If the tenants left, we would feel it financially.”

Seated in the main hall, we ask V. Sungaila what, in his opinion, unites deportees today. “Maybe the difficult period we lived through. During the Soviet era, there were all kinds of restrictions on studies and work. I remember that in 1984, I myself could not even go to Poland with my job; many have such grievances. But, as our poet Vytautas Cinauskas wrote, we are not here to leave vengeance on the earth, to be angry at someone. There was this system, we suffered, but now we are united by experiences and… songs. We always sing when we meet, we gather for song festivals, when all the exile choirs come together. Next year there should be a big one, though we don’t yet know in which city.”

V. Sungaila’s position in the union – chairman of the board – is similar to that of a prime minister. His colleagues jokingly call him the premier. What’s new, premiere? Although, as he says, he still has a “regular” job, too.

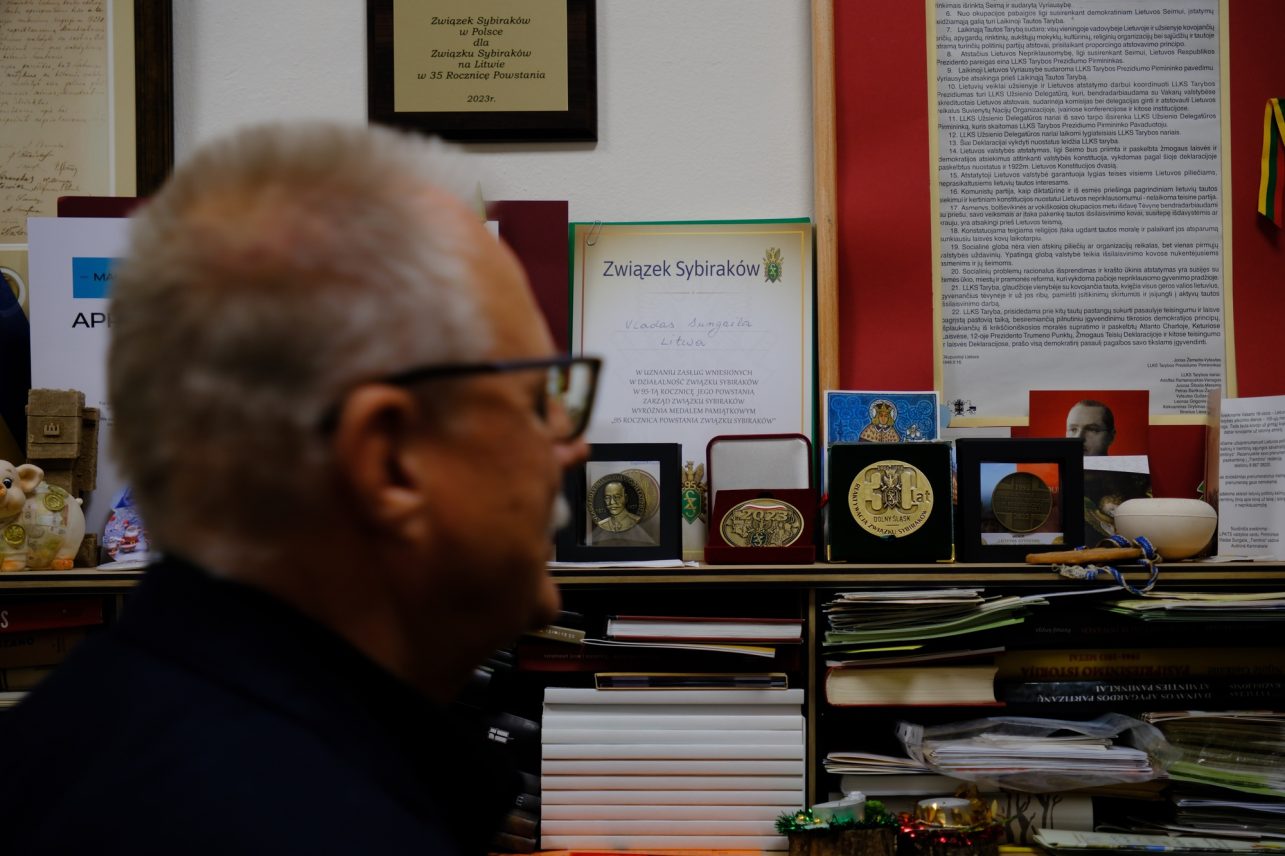

“To be honest, when there are long weekends, 3–4 days, I’m already looking forward to the day when I’ll go back to the union, where the calls will start, and I will meet like-minded people. People trusted me; they put my name forward. Once you start doing something, you don’t want to do it half-heartedly. We saw that the museum was gone, so we had to create a new one. During the quarantine, we cleaned everything and varnished the floors. We looked for sponsors. Little by little, we renovated the hall. Our main event, the congress, takes place in Ariogala. In 2025, we held the 35th congress there, an international one this time. We made friends with Latvian, Estonian, and Polish exiles. We started visiting each other. They were surprised that so many people continued to gather here. In Poland or Latvia, there are fewer left. We said, while it’s not too late, let’s do something. Now we’re reaching out to the European Parliament. We’ve practically signed the documents; the organization will be called the Baltic Alliance. We’ve patented the name and have a badge.”

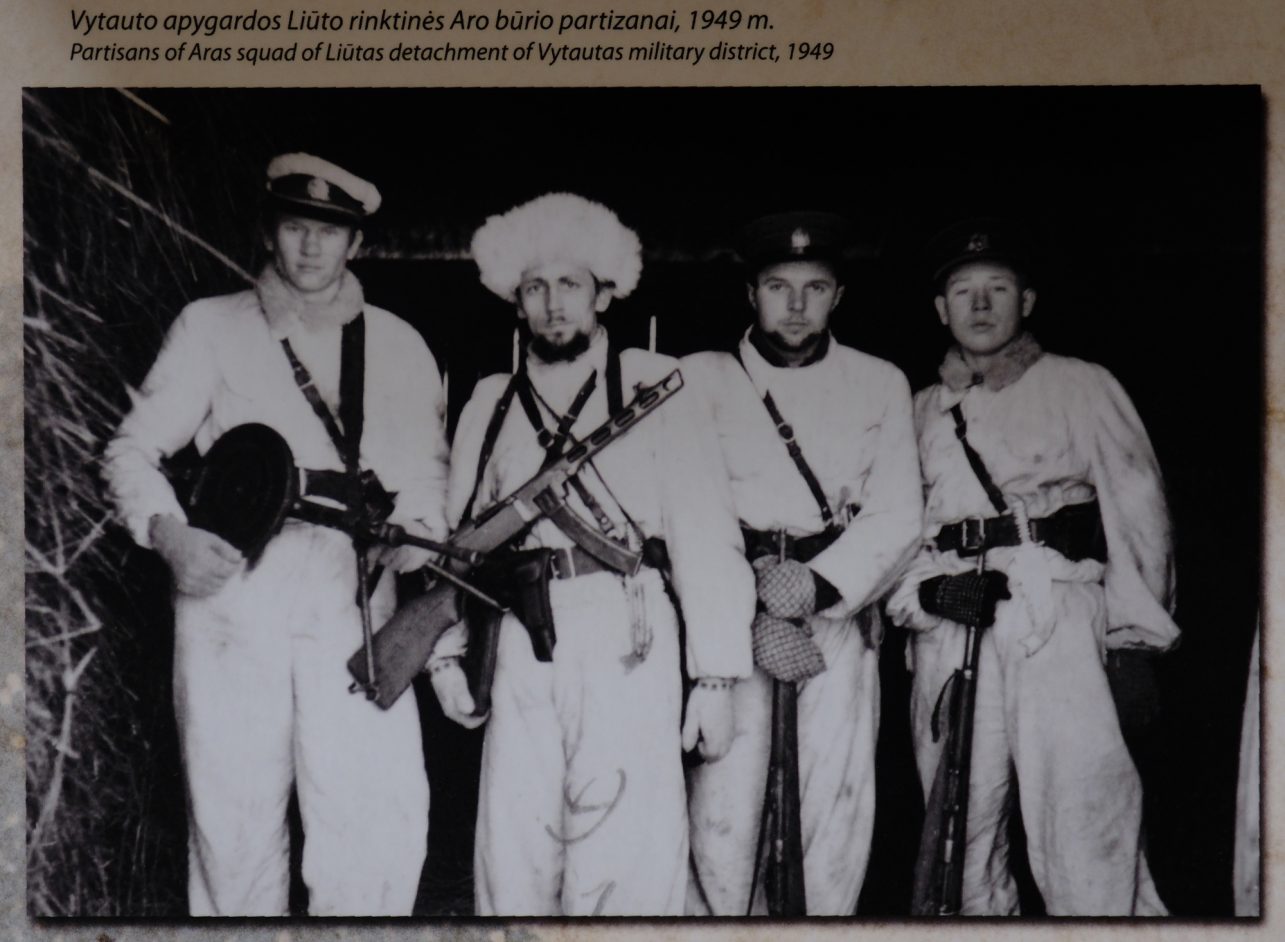

And what is Lithuania’s attitude towards the community of exiles, partisans, political prisoners, and their descendants? “Some are remembered very well; monuments have been erected, but more than 20,000 partisans were killed. It’s good that someone’s relatives survived, so someone can take care of the memory. But the state can’t even find the money to engrave the names on the Kryžkalnis monument. In Poland, the attitude is completely different; memorable dates are marked at the highest level. But here, well, we invite you, but…”

Still, unexpected, interesting, and joyful things happen, for example, foreign correspondents drop by accidentally, take an interest, and cover the story. For instance, the Portuguese, visiting the little bookstore and realizing that the books sold there were authored by exiles and partisans – not fiction – decided to translate at least a few into their language. There is little space here, but many modestly published works that you won’t find anywhere else. “Our main author, Stasys Abramavičius, has written about 15 books. People want those memories to remain so that others can get to know them.”

Our interviewee was born in exile. His parents – a farmer’s daughter and a partisan’s brother – were taken away as teenagers and met at dances where his grandfather played the concertina. His parents worked hard to return so that their son could attend first grade in Lithuania. They first came back in 1958 or 1959, in the fall, to his mother’s family home in Samogitia, but there was nowhere to live, no work available, and they couldn’t register. “We barely survived the winter, then gathered our belongings and decided that we weren’t needed here,” the interviewee recalls his parents saying. After spending another five years in Siberia, they saved enough money to return to Lithuania, buy a house where they could officially register, and look for work. And that’s how it turned out.

An interesting detail shared by the ever-energetic “prime minister,” who recently also became the chairman of the Kaunas Samogitian Society, concerns Lithuanian entrepreneurship. “Our people probably struggled the most during the first years of exile, but then they saw how things worked there, what plots of land were available. After work, they would dig a garden, plant something, and grow it. Even the Russians would come to buy potatoes from us. You’d save up money, buy a cow, and have milk. They say some were dispossessed a second time: the Soviet officials took everything away again and kicked them out. What can you do? Such was the government; such was the system. People were used to it; if you worked, you’d earn something. I remember my father bringing back a full backpack of cedar cones from the forest. He would blanch them, crack them, dry them, and in winter we’d have a bag of nuts.”

“But it must be said that a significant number of our people were simply sent to their deaths. Those who ended up in the northern regions… not everyone survived the first year. Disease, low temperatures, lack of food…” V. Sungaila continued. There were as many deaths as there were families as many torn destinies and shattered dreams and hopes as there were people. Perhaps the most well-known story of exile in Lithuania is that of Dalia Grinkevičiūtė. Her memoir “Lietuviai prie Laptevų jūros” (Shadows on the Tundra) was first published in 1988. A few years ago, there was a renewed wave of interest in her and her work in Lithuania. Exhibitions were organized, an animated film was made, and even a small museum dedicated to her was established in Laukuva, where she worked as a doctor. Grinkevičiūtė’s story is also featured in the LUPPD museum we visited.

“The Arctic. The Laptev Sea. You can feel the icy breath of the ocean. It’s the end of August, yet cold as deep autumn. Finally, we stopped. Before us lay an uninhabited island. There is nothing, no trace of humans; there’s not a house, not a yurt, no trees, no bushes, no grass. Only the tundra, locked in permafrost, and covered with a thin layer of moss. And a wooden plaque hammered in by some Arctic expedition declaring that the island is named Trofimovsk,” this and other stories can be heard by anyone who presses the scattered buttons on the map in the exhibition.

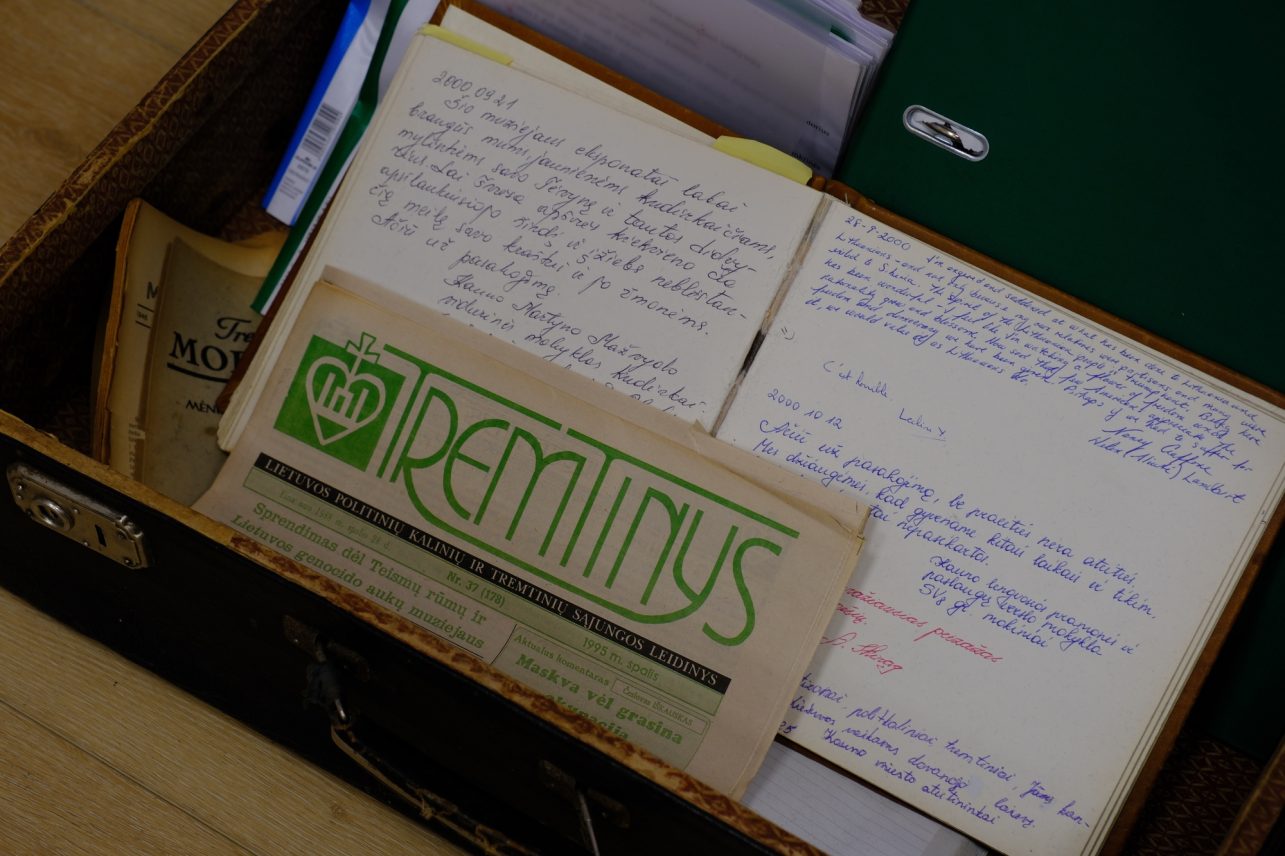

“We try to cover four stages in this little room: occupation, resistance, deportation, and the present day. Young people are impatient; after 10–15 minutes, they already want to press something. That is why we have installed terminals with various information: about the repatriation of remains, the restoration of monuments, searches for partisans, the memoirs of partisans and exiles, and the work of the union,” V. Sungaila showcases the exhibition. There are also some real artifacts, although after the museum on Vytauto Ave. was closed, most of the exhibits went to the capital. After visiting the museum, we go to the hall where films on the discussed topics are shown, the union has created a dozen of them.

According to V. Sungaila, the average age of the union members is already 75–90 years. Those born in Siberia are already over 70. “We have started cooperating more closely with the other associations I mentioned, because we are disappearing; maybe one day we will merge.” The most important thing now is for children to learn about what the exiled people went through, but it is difficult to attract them. “We cooperate with the Riflemen’s Union, especially the young riflemen, and invite them to events. We have approached those responsible for education so that there would be more history lessons about this past. It may be hard to change curricula, but when students come here, they react differently. At first, they are quiet and reserved, but when they look around the museum, see the terminals, and watch a film, then they say, “Oh, I remembered, my grandfather was there too.” Then they look back at their family history. Out of 20 children, not all of them will necessarily be interested, but if one of them becomes a historian, why not?” the interviewee asks rhetorically.