It seems that no matter if we learn something good or bad, there is always the question who taught us that. “Who taught you?” we ask a misbehaving child. “Who was your teacher?” we ask both young and older composers.

Although composing music is not martial arts, which requires maintaining a respectful relationship with the Master for a lifetime, yet some kind of relationship still remains. Because once the teacher was young and was also learning and, over time, the young composer becomes the teacher and passes on the knowledge further. This connection remains, just like branches growing out of the same tree trunk and bursting into leaves. And many Lithuanian composers’ branches grew out of the tree of Juozas Gruodis.

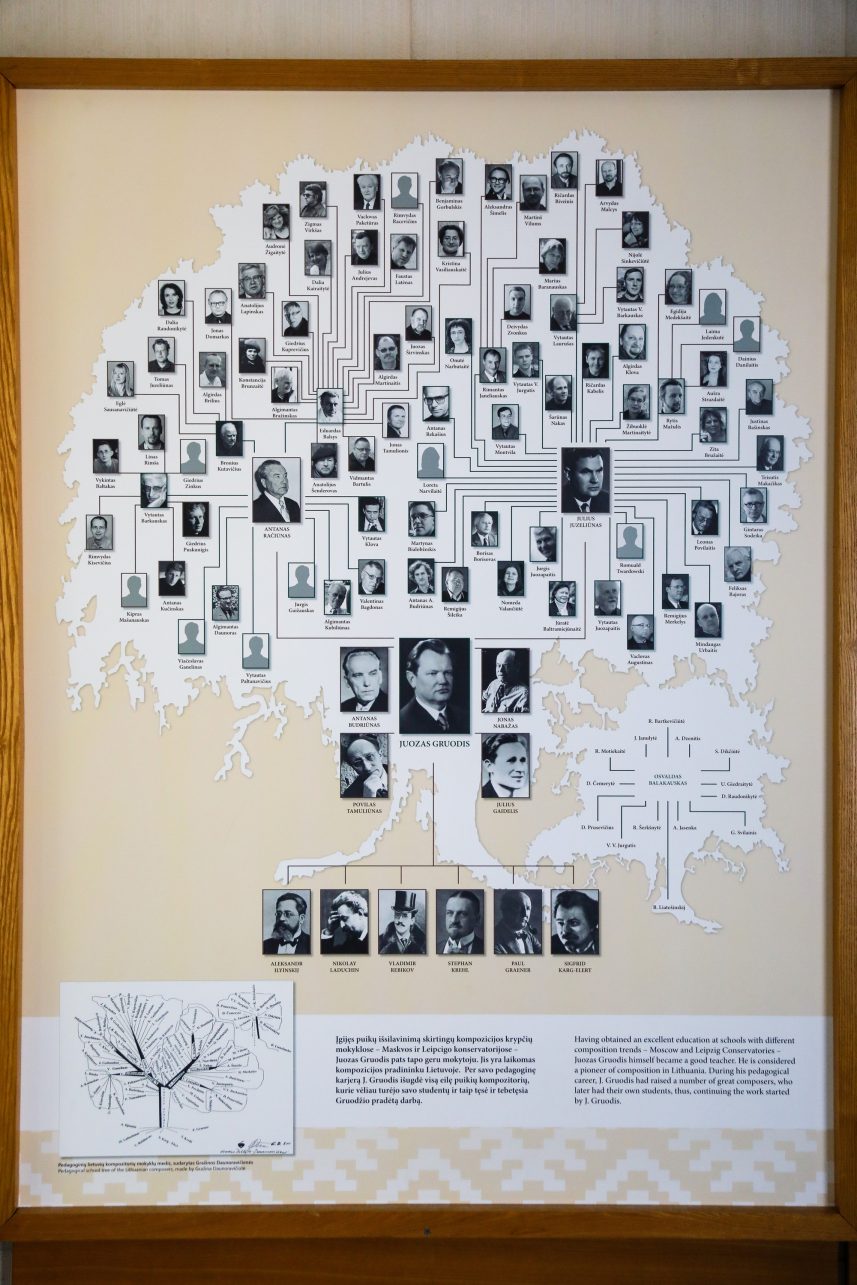

Juozas Gruodis at the Crossroads of Epochs. Articles. Memories. Documents (Juozas Gruodis epochų sankirtose. Straipsniai. Atsiminimai. Dokumentai. Algirdas Jonas Ambrazas, Lietuvos muzikos ir teatro akademija, 2009) is the book that features Prof. Dr. Gražina Daunoravičienė’s article “J. Gruodis’ School of Composers and its Branches” (J. Gruodžio kompozitorių mokykla ir jos šakos). In the article, she presents the tree of Lithuanian pedagogical composers’ schools that contains the trees of J. Gruodis and Osvaldas Balakauskas. J. Gruodis tree has two large branches of Antanas Račiūnas and Julius Juzeliūnas. A. Račiūnas creates V. Barkauskas, B. Kutavičius, and E. Balsys branches and J. Juzeliūnas creates V. Laurušas, R. Janeliauskas and R. Mažulis branches. My Work Alone is Noble exhibition set up at the Juozas Gruodis House of Kaunas City Museum features a lusher tree with more branches. Of course, today it would be even bigger, after all, the composers or students, who were young back then, are teaching composition themselves today.

When evaluating J. Gruodis’ life’s work, composer Jeronimas Kačinskas singled out his pedagogical work as the most important one. “One of the most important missions in J. Gruodis life was pedagogical work in the composition class of Kaunas Conservatory, where he spent more than 20 years. Some of his young students became prominent composers. J. Nabažas, J. Gaidelis and A. Račiūnas the students of J. Gruodis. In a short period of time, they have created valuable compositions that, in addition to strong individual characteristics, show a strong influence from their teacher. Understandably, it would have been impossible for a personality like J. Gruodis to not influence the devoted students, especially when his methods of teaching composition where of a more rendering nature.” Composer Konradas Kaveckas wrote about J. Gruodis’ composition class as a distinctive school in 1939, “He is not only one of the greatest and most original of our composers; he was also entrusted with the teaching of our younger composers. Therefore, it can be said that there is such a phenomenon like J. Gruodis’ school, the most prominent representatives of which would be his former composition class students J. Nabažas, A. Budriūnas, J. Gaidelis and others.”

And what sources did J. Gruodis use to draw the creative inspiration from? He received his initial knowledge of music from his family. Later he studied with Mikas Petrauskas and Povilas Latočka in Obeliai and Rudolfas Liehmanas in Rokiškis. In Mintauja he studied piano and singing privately with German-born pianist Alexander Geschmann. He studied composition with Nikolai Laduchin and Alexander Ilyinsky at the Moscow Conservatory. In Yalta he consulted with Vladimir Rebikov. At the Leipzig Conservatory, where he graduated with honors, J. Gruodis studied composition with Stephan Krehl, Paul Graener and Sigfrid Karg-Elert. Thus, in comparison with the schools of Latvian and Estonian composers, as G. Daunoravičienė emphasizes – although they are all connected to the Russian school – the Lithuanian J. Gruodis’ school is strongly influenced by the German tradition.

*

After founding the first composition class and evaluating the decade of the State Music School, its director at the time, composer Juozas Gruodis wrote, “The first concern of our music school is to get to know the seedlings of its own music; to learn to distinguish what is original about our music, what is peculiar only to us and what is precious not only to our nation but to the biggest cosmopolitans. The second concern is to get to know the music of the rest of the world and, after growing into the ranks of European artists, raise the culture of music throughout the country. Our third concern is to cultivate our music, refreshed with those juices that would make Lithuanian music vital even if we stopped using folk motifs in our compositions.”

Most of J. Gruodis’ students emphasised his punctuality, orderliness, demandingness, self-discipline, and diligence. G. Daunoravičienė states, “He tried to provide the students with strong professional skills and encouraged them to learn the rules of classical music thoroughly before embarking on a creative quest, and he did not compromise on the matter.”

Composer and conductor Juozas Karosas, who received his first musical knowledge from the young J. Gruodis, recalls, “Gruodis had set a specific time for my visits because the other hours were taken. His day was scheduled not only by the hour but by the minute, and he adhered to it strictly. … He was always on time. he was also very tidy. … From Gruodis I learned not only music but also great discipline, punctuality, and duty.”

According to composer Julius Gaidelis, “As a person, Juozas Gruodis was very energetic. That feature of his, as the director of the conservatory, had a positive effect on both pedagogues and the students. This had a positive effect on the level of education at the conservatory. The students of the conservatory – especially the young ones – found Gruodis too abrupt, unapproachable, but in reality, he was very democratic and sincere. Many times, I have witnessed him pressing ten litas into the palm of an impoverished student. Gruodis has also done a lot to Lithuania as a pedagogue. All our young composers, who graduated from the Kaunas Conservatory were students of Juozas Gruodis. And their work, more or less, reflects the influence of their teacher.”

Composer Jonas Nabažas, “When in the autumn of 1927 Gruodis announced that he is establishing a music composition class, me and four students of other specialties – A. Račiūnas, A. Budriūnas, A. Dirvanauskas ir L. Andriejauskas – offered our candidacy for the class. And after examining us a bit, J. Gruodis accepted us all to study composition. … He seemed quite different in this role than how he was as a conductor. Seriousness, professorial distance, as we experienced, was not typical of him at all; on the contrary, he was agile, natural, and even quite friendly towards us, despite the fact that, in addition to being our teacher, he was also a director.”

Julius Juzeliūnas, “When I went to Gruodis for the first time as a student, I was terrified, I was shaking… Gruodis, Gruodis, such a mysterious personality. Some were saying that he is extremely strict, others said that he was a good person. And after I saw him and met him, it turned out that all of the above was true: he was strict but also a really good person. He took care of his students because he thought that knowing your students – what they eat, what they wear, how they play the piano – knowing everything about them makes it easier to communicate with them and demand things from them. And that feature of Gruodis was good, him being so humane. And in addition to that, “Brother, you have to spend eight hours practising the piano. If you won’t then, there is nothing to discuss.” I tried to evade it. “Well, well, well, little brother, no need to be clever, if you will not practice, we have nothing to talk about.” During the first year, he forced me, and I sat for eight hours engaging only in harmony. Modulations, sequences, loads of problems… “Listen, brother, what are you thinking? Until harmony becomes second nature to you, we cannot speak of composition.” And so, I sat and practiced; what can you do.” J. Juzeliūnas also remembered the following teachings of J. Gruodis, “It takes a lot of work. You need to work and work; this is a prerequisite for a composer. Otherwise, you should not even think about studying composition. … There is no inspiration, brother, there is only work. … Brother, if you want to understand and figure out the Lithuanian harmony, listen to people sing, feel the totality of the mood and express it in your work as you feel it in your soul. There is no need to copy or imitate anyone because each artist has to speak their own language unique to them.”

Povilas Tamuliūnas, “When we visited the professor in his home, his wife would greet us very sincerely, with a smile. We would enter his room, and after a few minutes, he would appear in all his greatness, wearing a black suit with a white pocket square. As if ready for a party, the biggest gala.”

Vytautas Klova, “Professor Juozas Gruodis was a very sensitive person and a demanding pedagogue. Being extremely demanding and caring, he tried to pass it on to his students. He used to say that to be a good composer you need at least eight hours every day to work on your specialty. Students were required to do maximum work. If students completed the given tasks well, he would increase the number of tasks for the next class and did so until he was convinced that the student was unable to do more. … When composing works or solving harmony problems, he encouraged the search for more interesting consonances, texture, and melodics. At the same time, he demanded to account for each more extravagant consonance or a specific sound choice, asking to explain why it was written the way it was. Professor Gruodis was teaching us that in creation, everything, down to the smallest detail, must be well thought out and logical, that composition has to have an expressive melodic line, colourful harmonious garment, and a clear, concrete form without anything accidental in it.”

Antanas Belezaras, “As an educator, he was very strict, students were afraid of him. Once, correcting one of the student’s harmony compositions, he crossed many things out. The student argued, “But the rules allow it…” And Gruodis answered that with, “Your melody goes with the harmony as well as oil and water.”

Antanas Adomaitis, “J. Gruodis classes were not boring or official. “… You’re driving! Brother! You’re driving!” Gruodis would spell it out when the student wandered too far. “You know where you’re going? From Kaunas to Klaipėda via Zarasai.” After silently listening and following how the student is feeling about for chords, unable to find the way forward; listening to their quests for harmony, he would finally interrupt them saying, “Here my brother, you need to put on some pants! Without them, you can’t do anything… At first, I didn’t immediately understand what pants had to do with it. But after a pause, the professor explained in more detail, “It goes like this, musician! When you wear out about three pairs of pants against the chair, then you will know how to combine cords, but in the meantime, go home and work because you have issues with the first harmony.” Disputes were not really possible in J. Gruodis’ class, “We will discuss it in three years. We will be able to argue in five, and for now, just listen and do as I tell you. Taste needs to be acquired. Inner hearing needs to be developed. Everything is possible with intelligence and taste, but for now, you need to work my brother. Only work!” And this is how Gruodis spoke of his work principles, “My principle is this: do not adorn yourself with someone else’s feathers! Do not take what belongs to someone else, what is not yours. Creation is like language. If you have something to say, then say it! But if you don’t, then better stay silent…”

*

According to G. Daunoravičienė, “The successful knowledge transfer from the teacher to the student and how promising the students’ creations will be, are a few of the most important components in the content of the full-fledged musical composition school.” Let us look at this tree through the Kaunas’ composers from Lithuanian Composers’ Union (Kaunas branch), which is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year: Algimantas Kubiliūnas, Giedrius Kuprevičius, Dalia Kairaitytė, Zita Bružaitė, Giedrė Pauliukevičiūtė, Algirdas Brilius, Raimundas Martinkėnas and Viltė Žakevičiūtė and the ones who passed away: Jonas Dambrauskas, Viktoras Kuprevičius, Vladas Švedas, Vidmantas Bartulis, and Daiva Rokaitė-Dženkaitienė.

The senior members of the Kaunas branch were J. Dambrauskas, who graduated from the organ class of the Warsaw Music Institute and V. Kuprevičius, who took private music classes in his youth and later studied in a piano class at the Kaunas School of Music and polished his music composition knowledge with J. Gruodis’ student V. Klovas.

A. Kubiliūnas studied with J. Gruodis’ student A. Račiūnas, who was considered to be one of the most educated composers (after ten years of studying with J. Gruodis, he also studied in Paris with Nadia Boulanger and privately with Alexander Tcherepnin). G. Daunoravičienė notes, “A. Račiūnas’ pedagogical style and manner of working with students caused a lot of problems and did not always delight students.” When asked about studying composition at the conservatory, A. Kubiliūnas, who belongs to the branch of A. Račiūnas, answers politely, “Studying with A. Račiūnas was a very unique experience. He was a liberal, gentle and polite man. It is good that the conservatory, the department of composition, had a rather friendly student environment.” And when asked to specify, he explains, “Back then, we were all skeptical about studying with the professor but today, I am a bit more forgiving and understanding. It really was an almost independent work of the student and a real test of their creative prowess: if you did not fail, then you will continue… It forced the student to be fully responsible for themselves.”

G. Kuprevičius, D. Kairaitytė and V. Bartulis studied in the class of A. Račiūnas’ student E. Balsys. According to G. Daunoravičienė, E. Balsys drastically corrected students’ instrumentation works. “He was a real professional in both instrumentation and analysis; he would explain everything perfectly and provided many examples.”

G. Kuprevičius still emphasizes today, “My professor Eduardas Balsys kept repeating that if you do not add anything to your music, you will hear it. … Craft is very important to me because you can have hundreds of fascinating ideas, but you will not be able to unfold them properly if you will be lacking in skill.” The professionalism passed on by E. Balsys allows us to call G. Kuprevičius one of the most productive Lithuanian composers, who has perfectly mastered the orchestra. After all, he even “collegially extended a helping hand to the teacher”, because he “reviewed the score with respectful distance and edited it slightly.” J. Katinaitė empasizes, “The students of Balsys – the role model of orchestration – are well taught to feel the orchestra.”

It is interesting that G. Daunoravičienė considers E. Balsys to be the professor who has interfered with the student’s creative process the most, however D. Kairaitytė does not agree with it, “Prof. E. Balsys’ teaching methods were based on the key norms of classical art: to strive for clarity of form and balance of various elements of expression, a harmonious relationship of emotional content with compositional technique. E. Balsys had an individual relationship with each of his students, he looked for ways to reveal the best qualities of the student, and he tried to convey the knowledge to everyone intelligibly. … I remember the calm and slightly hoarse voice of the professor very well when at the beginning of the class he carefully “read” notes with his inner hearing, then took some time to think and after that, using carefully chosen words, explained why, in his opinion, this or that part of the composition should be adjusted. E. Balsys never corrected notes on the student’s work (underlined by D. K.).”

It is interesting that during the conversation with R. Gaidamavičiūte V. Bartulis has admitted, “I did not learn anything at the Conservatory, so I am not really committed to anyone. E. Balsys allowed us to do whatever we wanted, it only had to be convincing. He would get very happy with every deviation from the form that we had analyzed a month ago, and not so happy if he saw that everything was correct.”

The other branch belongs to Julius Juzeliūnas. According to G. Daunoravičienė, “Juzeliūnas worked with the students differently, trying to make them open up on their own and show the depths of their souls that they perhaps were not aware of. J. Juzeliūnas would not touch the students’ scores in any way.”

There are several students of J. Juzeliūnas among Kaunas composers: V. Švedas, who was encouraged to create by A. Belazaras, Z. Bružaitė, and G. Pauliukevičiūtė as well as D. Rokaitė-Dženkaitienė, who attended B. Kutavičius and J. Juzeliūnas classes.

Z. Bružaitė emphasizes J. Juzeliūnas’ way of developing professionalism, “He constantly reiterated his opinion that in addition to God-given talents and abilities, it is equally important for a composer to be able to use the necessary compositional tools, such as sense of form, understanding the instruments, elementary musical literacy, the prospect of genre development combined with the latest means of expression, compositional methods, and notation. And finally, personal qualities, which are necessary not only for creative process but also to implement the work.”

What seems to connect J. Juzeliūnas to J. Gruodis is the gentle way of addressing students, only instead of “brother” used by J. Gruodis, J. Juzeliūnas students were “nightingales”, “flowers”, “petals.” He also emphasized hard work in exactly the same way, “Inspiration is not a bird, it will not fly in if you open the window.”

G. Pauliukevičiūtė also studied with J. Juzeliūnas, albeit briefly. She speaks about her teachers – B. Kutavičius, O. Balakauskas, and J. Juzeliūnas – with great respect, “I always waited for the lectures of my specialty. They were different from music history or harmony lectures. Maybe because they were individual. Professor [B. Kutavičius], having inspected the work done, asked you to play. After that, we would talk for a long time about the compatibility of the idea and the musical material, the form of the work. Always tolerant, inspiring, and supportive, the professor led the entire period of undergraduate studies. When doing my master’s I studied for a year with professor Julius Juzeliūnas and then a year with professor Osvaldas Balakauskas. I am extremely grateful to Professor J. Juzeliūnas for his advice on instrumentation, and to professor O. Balakauskas for the secrets of musical language and form composition, and to all of my teachers for the knowledge, constant support, encouragement, and kind communication.” Algirdas Brilius is also a student of B. Kutavičius.

Interestingly, there is an increasing number of young composers who have studied with more than one teacher as if returning to J. Gruodis’ own diverse studies. This type of studying was chosen not only by G. Pauliukevičiūtė, but also by Raimundas Martinkėnas, who studied with Ričardas Kabelis and R. Janeliauskas, and the youngest member of the Kaunas branch of Lithuanian Composers’ Union, Viltė Žakevičiūtė, a student of R. Kabelis, Raminta Šerkšnytė and Mārtiņš Viļums. What branches do these composers grow from? R. Kabelis, like R. Janeliauskas, is a student of J. Juzeliūnas, M. Viļums is a student of R. Janeliauskas, and R. Šerkšnytė grew out of a completely different O. Balakauskas’ tree.

When asked about her studies, V. Žakevičiūtė presents a detailed report, “R. Kabelis was my first composition teacher at the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre. When I entered the professor’s class, I knew it would take a lot of hard work. The first year of my studies was the most memorable because only then did I really understand what the art of composition was. As a lecturer, R. Kabelis stood out with his sternness and adherence to stricter rules in creative work. After all, it was very important in the first years. Later I studied in M. Viļums’ class where I faced other types of challenges. With M. Viļums, during the lesson, we paid a lot of attention to philosophy. We talked about what music is, and what tools can we use to achieve the version that is closest to our hearts, but we didn’t rule out the smartest options either. Both R. Kabelis and M. Viļums pay a lot of attention to rationality and precomposition in their work. Even if both have their own methodologies and create differently, they are both for the structuring of music. R. Šerkšnytė’s class was also very interesting. I faced an even more different approach to music, thoughts, outlook. We also talked a lot about music with the teacher; about what we liked most about it. She probably stood out most from the others in her organic nature. Rationality and intuition are equally important in her work. I am very glad that I had the opportunity to learn from different teachers. I am currently continuing my studies in R. Kabelis’ class. I have come full circle!”

And R. Janeliauskas, who taught R. Martinkėnas, is a unique pedagogue, who himself does not compose music. He has successfully trained Marius Baranauskas and Mārtiņš Viļums, who both compose music and teach. His students, like him, encourage thinking, and conversations take place on an ideological plane. M. Viļums, who considers himself a follower of R. Janeliauskas, has this to say about his teaching, “Music composition must reveal the spiritual path of a composer, existential connection with the world and personal relationship with sound.”

When asked about the composers who taught the composition, R. Martinkėnas points out that R. Kabelis emphasized the strict musical structure and “R. Janeliauskas is broad-minded and is able to provide many interesting comparisons, suggestions, and solutions related to ideas, development of your work etc., because of his wide-ranging experience in music compositions, style identification and classification. And all that is much more motivating, both emotionally and creatively.”

These are the branches of J. Gruodis’ composers in Kaunas – lush and green. And as A. Ambrazas suggested, “The term “school” should not be understood in a literal sense. It’s not just the number of students, rather, most importantly, the general direction, ideas, and principles. Principles that are passed on like a baton from generation to generation.”