Until the Second World War, wooden construction was an essential part of Kaunas’ development. The city is diverse in its architectural forms and stories about the needs, possibilities, and fashions of its citizens. I have selected a few quite different wooden buildings located in various parts of present-day Kaunas for you. These are buildings whose stories are perhaps remembered a bit less frequently.

Juškėnas House. Alantos Street 12, Žaliakalnis

Although individual development in the relatively small part of Žaliakalnis took place before the First World War, Žaliakalnis can justifiably be considered the most important part of the city that formed during that time. If in the 1930s we see many interesting examples of modernism emerging here, the 1920s were marked both by abundant utilitarian architecture and by quite exotic cases ranging from ornate villas built in the fashion of historicism to so-called national style experiments.

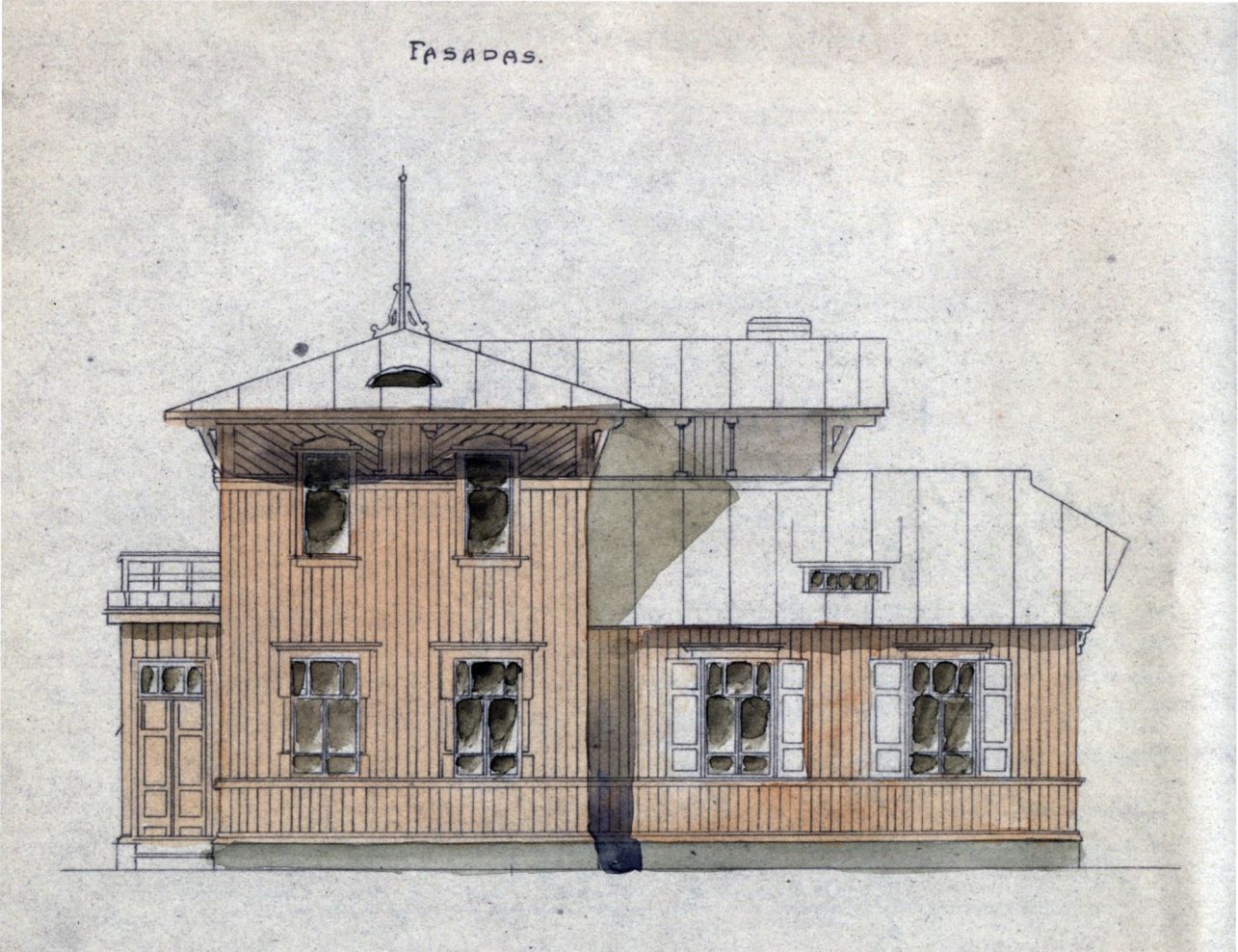

In what was then a relatively remote area of Žaliakalnis, on present-day Alantos Street, surrounded by architecturally unremarkable neighbors, technician J. Juškėnas designed a distinctive residence for himself. This suburban villa, featuring elements of the so-called Swiss style (a rare choice in Kaunas), would not have looked out of place in prestigious resorts. The interior layout was also planned to be unusually spacious. Today, it remains a rare example of a building in this part of Žaliakalnis that has changed little from the architect’s original vision.

Sruoga family house. B. Sruogos street 21, Žaliakalnis

Our readers might not be entirely unfamiliar with this house; we have written about it and the activities that take place there more than once in our magazine. In the late 1930s, writer Balys Sruoga and historian Vanda Sruogienė built a new home on what was then the outskirts of Kaunas. To be fair, they didn’t build it from scratch but rather rebuilt it. First, Vanda’s father, Kazimieras Daugirdas, built a house in 1937 in the distant Būgiai (Mažeikiai region) based on a design by renowned architect Vladimiras Zubovas. In the summer of the following year, the house was dismantled and transported by rail to Kaunas – the Sruogos had only managed to furnish part of the house before the occupation, which dispersed their family.

After the war, Sruoga returned to the house only for a short time; other families lived in the building until the 1970s. Later, a library was established there, and the writer’s memorial room was created, which gave birth to the current Balys and Vanda Sruogos House Museum. The building is interesting not only for its unusual construction history, but also as a relatively authentic example of a modern wooden house from the late 1930s.

The center of an unbuilt resort. Buriuotojų street 5, Petrašiūnai

“Kaunas will have the most modern resort in Lithuania”, proclaimed the headline of Lietuvos Aidas in 1934. Indeed, far beyond the city’s administrative boundaries, and some distance from the industrial suburb of Petrašiūnai, a new holiday village was to be built in the depths of Pažaislis pine wood. The project was the brainchild of Antanas Vaitkevičius, the head of the Savings State Treasury. It envisioned a complex of 45 buildings on a beautiful, two-hectare site.

Holiday homes of 30, 40, and 50 square meters (the standard designs were prepared by architect Aleksandras Gordevičius), which, together with a plot of land, were supposed to cost between 3,000 and 4,200 litas, and, as the journalist J.K. Beleckas wrote, were supposed to be affordable for a “middle-class official or a freelance, because the prices are not too high, and the terms of payment are convenient.” Each building was supposed to have had a plot of land adjacent to it where the owners could engage in gardening, horticulture, or have a sports field. A two-story building was erected at the highest point, which was supposed to become the center of the resort: the ground floor was to house a shop and a telephone exchange, and the resort’s guard and groundskeeper were to live on the second floor.

This may not be the most distinct building among Kaunas’ wooden houses, but it represents an interesting and now-forgotten story. Unfortunately, only a small part of the resort was completed before the occupations, and later, the cottages and the two-story “resort center” became simple residences; some were demolished when a railway branch to the Kaunas hydroelectric power plant cut through the idyllic neighborhood during the Soviet era. Most of the remaining buildings from this unrealized resort will soon be cleared away to make room for the new city bypass.

Old St Casimir’s Church. Antakalnio street 35, Aleksotas

We probably wouldn’t be wrong in saying that one of the main symbols of Aleksotas is the crown of St. Casimir’s Church, proudly rising above the treetops, a landmark once gifted to the area by the late architect Algimantas Kančas. In the shadow of this postmodern sanctuary lies a much humbler structure – its predecessor, the old wooden St. Casimir’s Church. Like all former suburbs of Kaunas, Aleksotas expanded rapidly during the interwar period, known as the Temporary Capital era.

The settlers didn’t have to think much about building a new church: the sanctuary was built here at the very beginning of independence. The famous Vailokaičiai brothers, who acquired the land of the local Kinderiškės (or Gintariškės) manor, were two of the initiators of the establishment of the parish and donated a plot of land for the future building. The church was constructed in several stages: the initial structure was erected in 1921 using materials from an old farm building, and in 1923, the church was expanded based on architect Valerijonas Verbickis’ design, taking on its current appearance. In Kaunas, it stands as the largest example of folk-style wooden sacred architecture, as well as an intriguing monument to the early period of Independent Lithuania, which was limited by financial constraints and whose architecture remains somewhat undeservedly overlooked today.