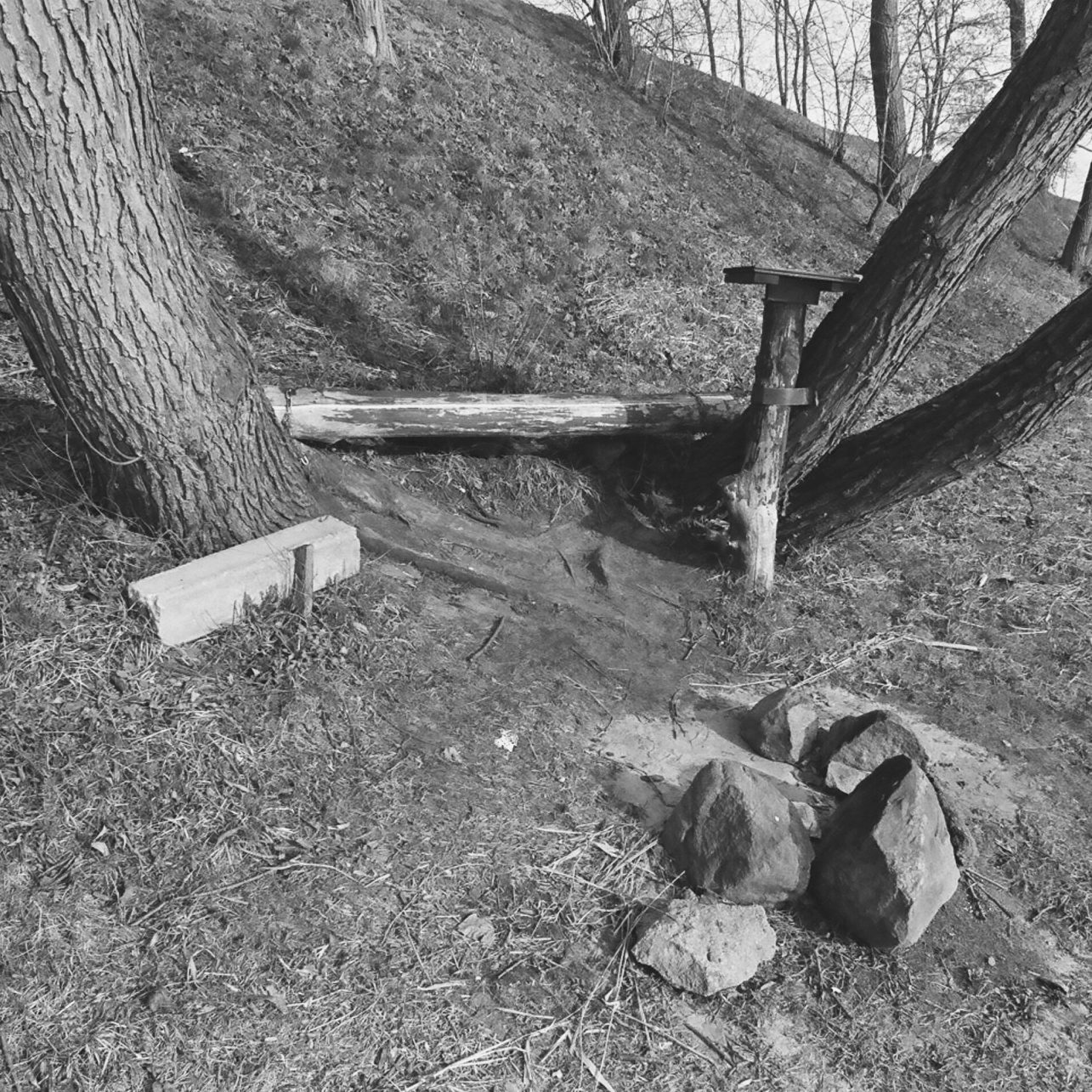

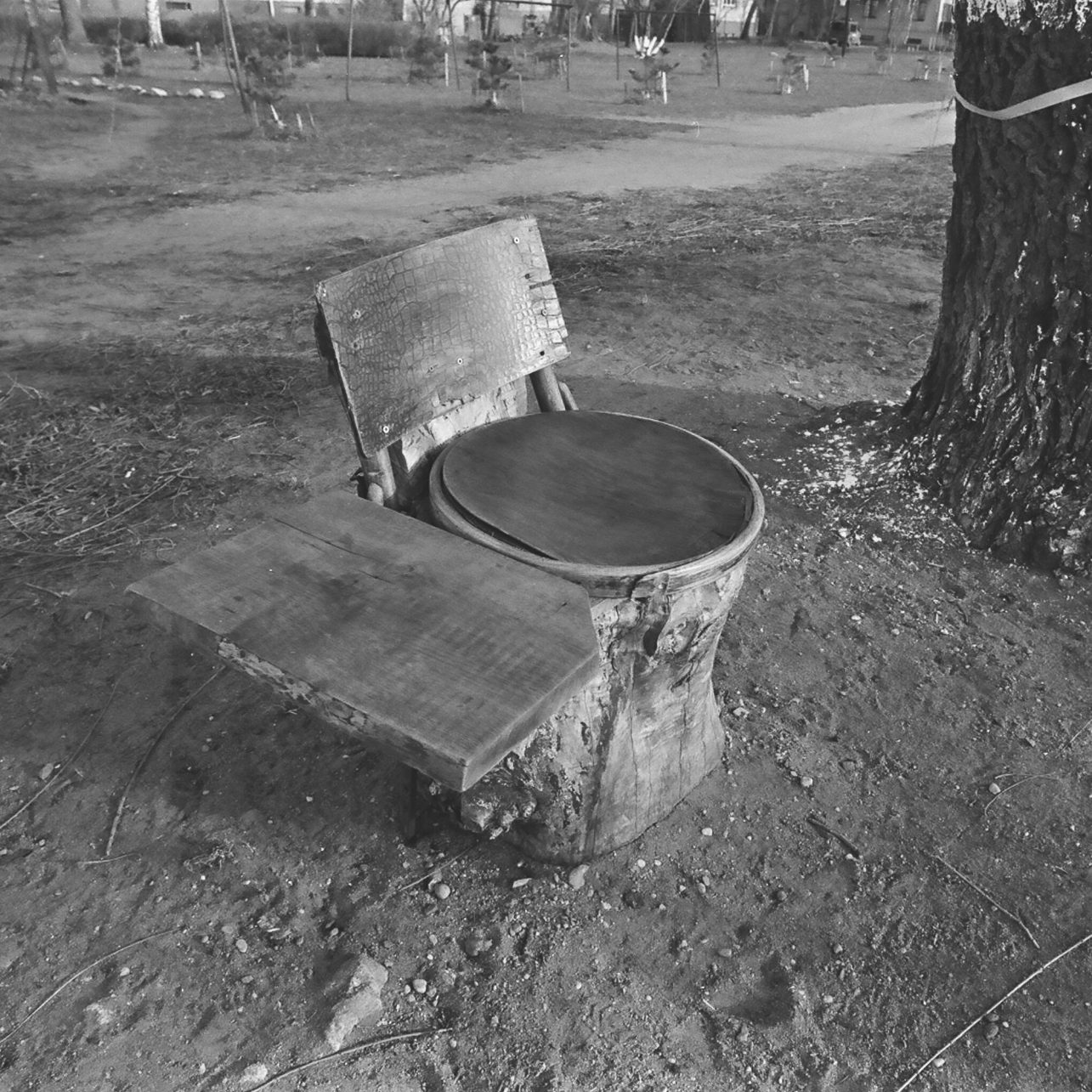

The Architecture of Inebriation is a photography series that I have been developing since 2020. It captures self-made objects of utilitarian small architecture and design in various recreational spaces (riverbanks, parks, gardens) in Kaunas and Vilnius. The photographs published in this article were taken on the banks of the Nemunas in Šančiai.

The buildings and furniture, adapted by the locals for respite or picnics, are suitable, and often intended, for getting intoxicated in the bosom of nature, and are themselves aesthetically inebriated: crooked, cheerful, straightforward and barely able to stand on their own feet. So, let’s talk about them.

Inebriated or drunk architecture is nothing new – there are many well-known and suspiciously polarizing buildings, such as the Drunk House in Sopot, the Dancing House in Prague, or Dancing Houses in Amsterdam that resemble revelers swaying shoulder-to-shoulder. Both these famous examples and the anonymous folk-inspired structures found around Kaunas and Vilnius share common features: asymmetry and a lack of balance in their posture, which serve as a compelling visual metaphor for dizziness or inebriation.

Philosopher and art critic Denis Dutton’s writings combine Darwinian evolution and the philosophy of aesthetics. He argues that the appreciation of art is deeply rooted in biology and evolved as a natural part of human nature. The human tendency to create and value art is not merely a product of culture; it is a trait shaped by natural selection. Dutton claimed that humans possess an “art instinct” – an innate tendency to create, appreciate, and feel an emotional connection to art. This instinct evolved from the need to strengthen social bonds, encourage communication, and even had influence on mate selection.

Indeed, the architecture of inebriation reflects the natural, primal instinct to do something with a more peculiar stick or stone that we found on the ground, and at the same time somehow civilize, tame, and adjust any environment that we tend to stay in for some time to our needs. The best part is that some of these structures have the same level of ingenuity and craftsmanship as those of our prehistoric relatives. This creates a pleasant sense of continuity – just like them, we can’t just pass by a cozy shelter by the river, and just like them, having found a good stick, we grab it and start building something.

When thinking about these amateur structures or pieces of furniture, one could choose not to look beyond their utilitarian function and avoid venturing into vague associative interpretations. However, we would have a more enjoyable intellectual adventure by attributing creative ambition to these objects. Once we do that, layers of folk art, ready-made, and arte povera movement traits begin to unfold, not to mention the relevant aspects of upcycled design and environmentally conscious reuse of materials. Variance and communality that are characteristic of folk art can be found on the banks of the Nemunas River – fiercely defended by local residents – in the Šančiai neighborhood, where the shadows of the trees and shrubs hide a variety of wooden resting spots. Office chairs that smell of formality and Excel sheets, find themselves in the gardens and courtyards of Vilnius, with the alien quality of ready-made objects. Removed from their natural environment, they are disturbing, while buildings or furniture made from the debris of these and other objects have the impression of arte povera.

Ultimately, an essential element in the emergence of intoxicated architecture is the factor of aesthetic appreciation, specifically the relationship between a bench and its surrounding landscape. According to Dutton, what we consider to be beautiful in nature – especially in landscapes – is no accident. It reflects millions of years of human adaptation. Beauty, in this case, is nature’s way of guiding us towards environments that are conducive to survival. Across cultures, beautiful landscapes are seen similarly – they resemble the African savannas where humans evolved during the Pleistocene. This ideal landscape includes open spaces with low grass, clusters of trees (groves), especially those that branch low – one could climb them in case of danger – as well as a visible source of water: a lake, a river, or at least a shade of blue in the distance, signs of animals or birds, a road, a trail, or a shoreline.

In urban areas that have this potential for beauty and shelter, but are forgotten by urban planners, footpaths are always trodden, logs are dragged into the shade of trees for sitting, and benches are hammered together. The parts of the city’s riverbanks and parks are dotted with makeshift respite spots – the self-regulation of recreational spaces.

Of course, these zones of inebriation are often accompanied by the threat of garbage piles and shady company, but stunning design and engineering solutions redeem this.