“I am more like my grandmother than my mother,” Vytautė Trijonytė says. Her grandmother, Danutė Kastutė Eidenienė, worked in the Koton (formerly Cotton) factory in Šančiai since April 1964, and today she is retired in one of the Dainava apartment blocks.

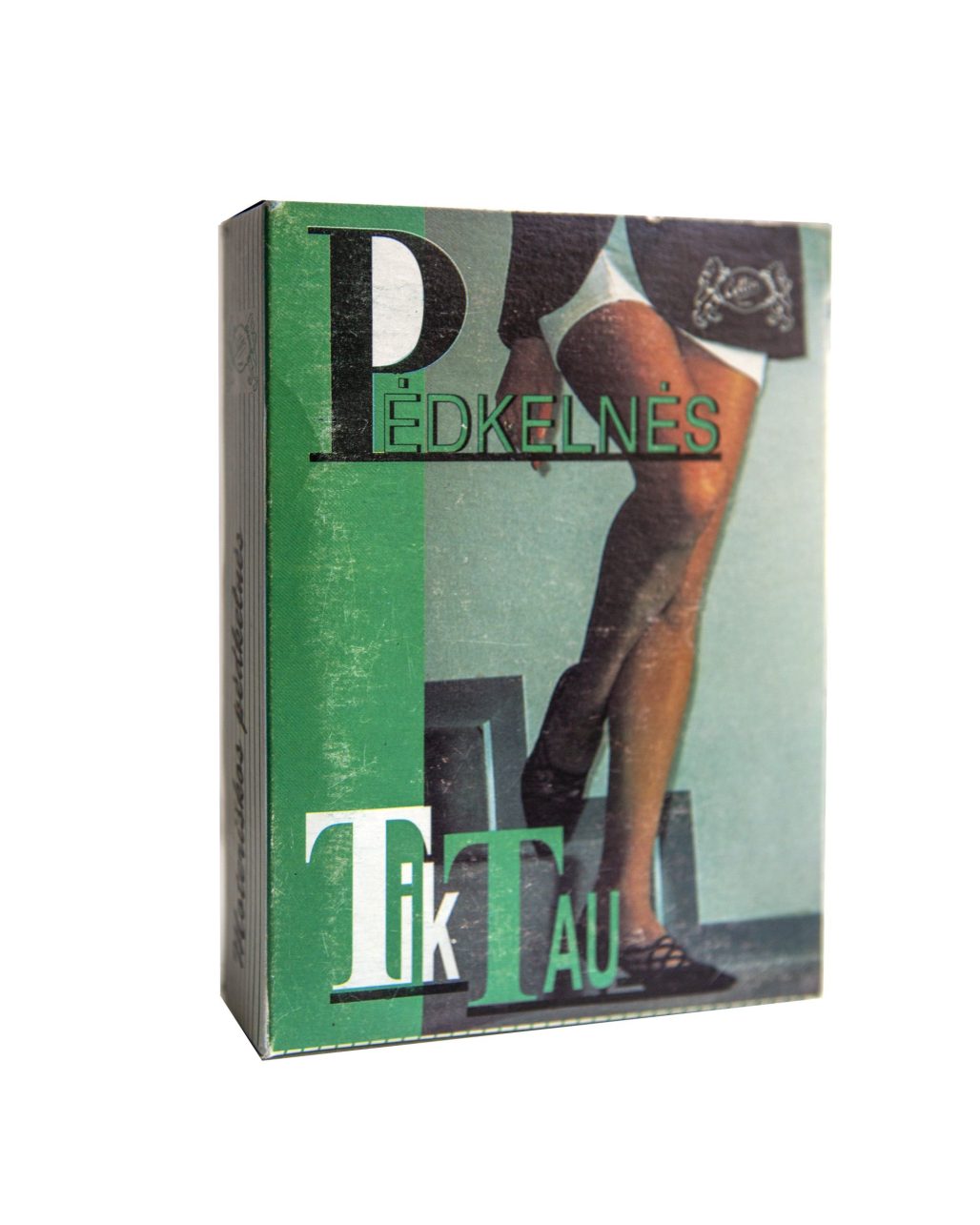

Women’s stockings and the Soviet occupation, the concept of beauty and femininity behind the Iron Curtain, and the relationships between the older and younger generations as consequences of historical upheavals – all of this fascinates Vytautė, who was born after the restoration of Independence. The artist, who studied photography in the United Kingdom and Belgium, recently presented an ongoing artistic research project titled Kotonas, in which she explores all these questions.

It all began with Vytautė’s father, who agreed to be the main character in her photographic project Homo (Sovieticus). A close connection with family members who lived under occupation, and the exploration and evaluation of their memories, are important in understanding how things truly unfolded and how people had to act. Later projects were less personal but still focused on the past.

“And then came the realization that my grandmother wouldn’t live forever. I wanted to honor her story, even though she didn’t find it interesting,” Vytautė recalls how she decided to include her mother’s mother in her work. This grandmother, unlike her father’s parents, lived in Kaunas. So, for the girl who grew up in Raudondvaris, “the village” was actually the city, where it was fun to spend summers.

Vytautė doesn’t remember her grandmother working at Kotonas – by the time she was born, the last entry had already been made in her Soviet work record book, confirming that the entries stopped in May 1993, and that a state social insurance certificate had been issued. But Danutė was happy to share funny stories with her granddaughter. For a woman born during the Second World War, the sock factory was her first and only job. She was a responsible employee. Her employment record book contains many entries about bonuses granted for “good production indicators”, “active work in the fight against embezzlement”, and “honest work.” Although it is commonly believed that in those days everyone stole, hustled, and otherwise added to their salaries, Vytautė’s grandmother was not one of them. She even says that people thought she was a spy because she did not steal.

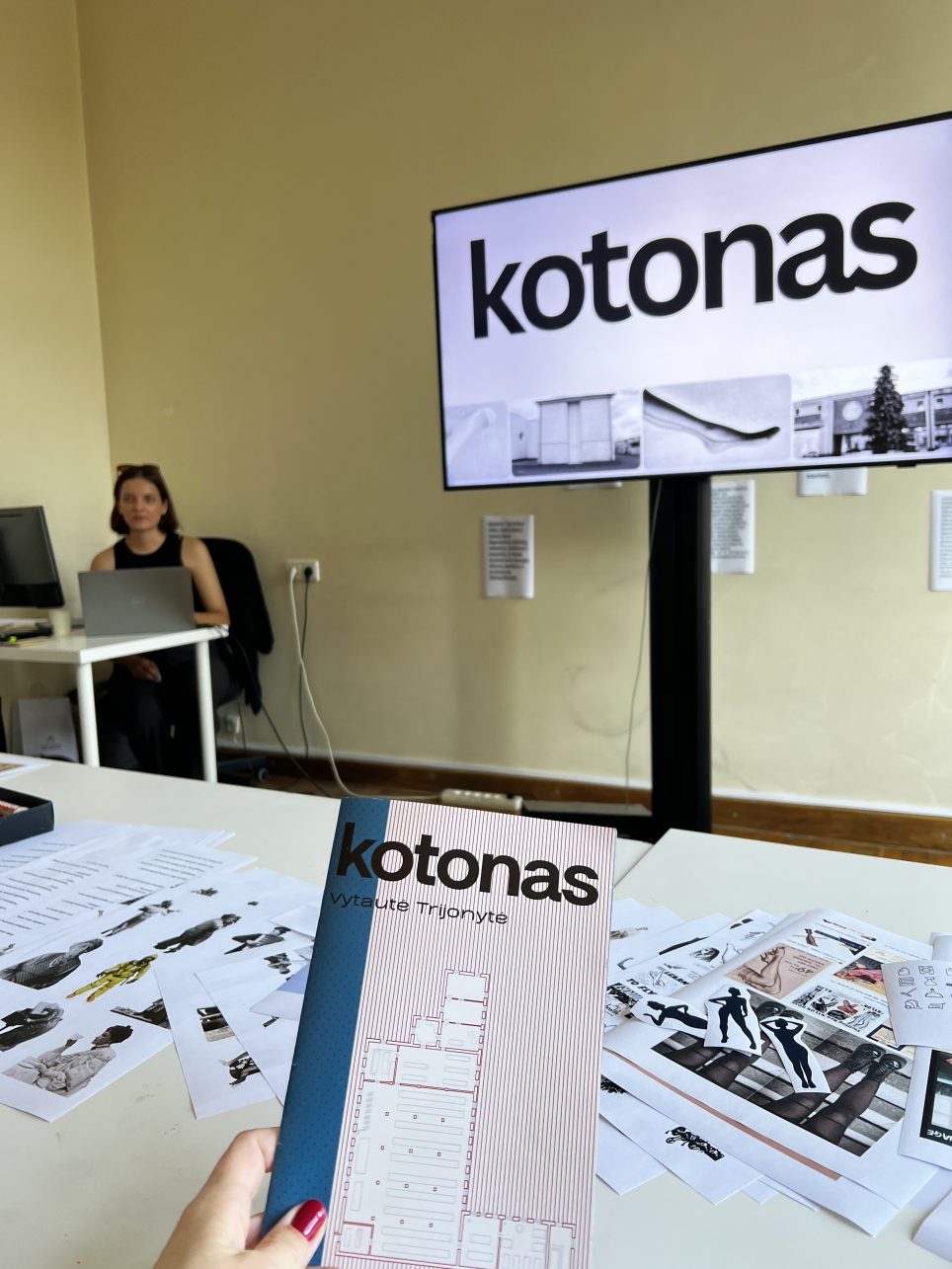

“I don’t know why they didn’t give me a job as a cleaner. Maybe because I was pretty. People used to say so,” the grandmother told her now grown-up granddaughter, who asked her to share her memories of working in the factory. This thought is quoted in a small-format publication, which is called simply Kotonas. I gave it to my grandmother last Christmas, and she was delighted, although maybe she still didn’t fully understand what it was all about, why anyone would be interested in her story,” Vytautė says, presenting the zine-like publication.

The publication is illustrated with images created by the photographer herself. She took her grandmother to Šančiai and walked around the Kotonas factory complex. Grandma saw a lot of things that had changed and was amazed by the new extensions. There are very few old photographs in the publication, and the reason for this is very simple: Grandma simply burned them all. When the apartment was flooded and she had to move elsewhere, it did not seem important to her to preserve the memories, which were diligently recorded by her husband, also a photographer, who understood the importance of documentation. “There was disarray, a general sense of disappointment,” Vytautė remembers. She accidentally told her mother – for whom it is very important to keep and preserve everything – that the grandmother destroyed the old photographs.

I ask if the grandmother was Vytautė’s ideal of a woman when she was little. “My grandmother was a strong woman. Maybe not entirely feminine by conventional standards. Both she and I were mischievous as children. And later she never became a “proper” lady, or some refined woman. She was more playful. I admired that. She even taught me how to curse and gave me tips on how to tease my older sister.”

Another element of the study was a survey in which women of different ages gave their personal conceptions of what it means to be a woman. Only fragments of the answers are presented, but not the context; we do not see the age or profession of the interlocutors. “A woman is a bright hope, no matter how many experiences, trials, losses, ups and downs she endures, she is always radiant with energy, warmth, coziness, and above all, HUMANITY,” one respondent says. I wonder whether the survey would have been different if her grandmother had worked, say, in the Inkaras factory and made sneakers instead of socks. “Yes, it’s a happy accident, the product adds charm, but if my grandmother had made screws, I would still be interested because it’s not about the product, it’s about the presence of the people and their footprint,” the artist answers.

Part of the artistic research of Kotonas is reading the Tarybinė moteris (Soviet Woman) magazines. When Vytautė organized a presentation evening at the Kaunas Artists’ House, where she was part of the residence for a few weeks, we all looked at the thick binders full of the magazine’s issues. “It gave me a better understanding of the years of occupation, the people of that time, and also explained the origins of the stereotypes about femininity that still exist today,” Vytautė says. According to the artist, Tarybinė moteris was quite a phenomenon at the time, and the propagandistic and educational texts published in the coveted, widely read magazine were of great importance. It is difficult for Vytautė to evaluate today’s women’s magazines; she doesn’t read them precisely because she doesn’t see their value and meaning, “Today, we have many other sources that have changed the truth of one magazine.”

Like the other large factories, Kotonas also had its own traditions, balls, and meetings (curator Auksė Petrulienė’s platform Small Stories tells about the human face of the Kaunas industry, and I highly recommend it, ed.). Even a booklet dedicated to Kotonas was published; one grandmother’s colleague preserved it. However, Danutė did not maintain a strong bond with her fellow employees, and after leaving her job she became much quieter and more withdrawn. “Although, as far as she told us, she did a lot in the 1990s. She was an activist, a member of the Reform Movement, a social activist; she gave an interview, but we can’t find it, because she doesn’t remember exactly who printed it, maybe Komjaunimo tiesa,” Vytautė laughs. It is worth mentioning here that the Kaunas resident works at the Ąžuolynas Library, where many volumes of Lithuanian periodicals are kept. I hope that at the next presentation of Kotonas we will read the historical conversation.

Danutė’s granddaughter also asks herself the question of why others should be interested in this, and she is quite open about the doubts. However, she believes that she is interested in this story not only because the woman from Kaunas who worked at Kotonas is her relative. “I am interested in how the past contributes to the present. It can encourage others to look into the family archives and give new meaning and significance to stories.”

Is the Kotonas project finished? No. During her residency at Kaunas Artists’ House, Vytautė tried to move away from what had already been created and explored, because she didn’t feel that she had revealed what she wanted. Her plans include recreating her grandmother’s memories in front of a camera lens. It’s also not the time to put the Tarybinė moteris’ sets back in storage, perhaps the magazine articles read aloud will become a sound art project. “I told Kaunas Artists’ House curator Agnė that Kotonas will probably be my life project, I still have a lot to do, I haven’t fully told my grandmother’s story or maybe I haven’t found the best way to do it yet,” Vytautė says.

vytautetrijonyte.net