Spirit rather than the letter, as they say, but names are important for historic Kaunas factories. If only because that is often all that remains of them – production has stopped, employees have dispersed, the land and buildings have been swallowed up by real estate, but the names of the factories still resonate today because memory loves beautiful names.

(Text published in the magazine “Kaunas Full of Culture” 2025 October issue “Signs”)

Mama factory

“We’ll produce everything we need ourselves!” – this slogan of the newly restored independent Lithuanian state echoed through the temporary capital as factories began sprouting rapidly. More precisely – fabrikos. Back then, the noun was of the feminine gender, as in many European languages to this day. Fabrika – the one that produces and multiplies, a mother of prosperity who feeds and clothes her children. Advertising signs and newspapers flashed with the names of the beautiful Kaunas factories: Drobė, Silva, Jėga, Lima, Flora, Tilka, and even Lituanica. Some, however, bore masculine names – Vilkas or Inkaras.

A rubber symbol of hope

The origins of the pre-war factory names can no longer be traced – we can only guess. For example, an intriguing mystery is the rubber footwear factory Inkaras (Anchor). It was founded in 1933, rather late compared to its closest neighbors in the rubber industry – Trikampis (Triangle) in St. Petersburg, which had been operating since 1860, and Keturkampis (Square) in Riga, since 1924. The names of those neighboring factories were entirely minimalist, simply named after the mark stamped onto the soles of their shoes – a triangle or a square. Inkaras’ competitor, Guma (Rubber), established nearby in Vilijampolė in 1938, lured away half of Inkaras’ workers by offering better pay and working conditions. But what a primitive name!

In Soviet-era factories, miraculous things often happened, born from the resilience of the communities themselves.

So, alongside the triangle, the square, and – pardon the expression – the stinking rubber (guma), the name and logo of Inkaras (Anchor) – vivid and metaphorical – seem to belong to another world. It is speculated that the idea for such a name may have been inspired by the plot of land purchased in Vilijampolė for the factory’s construction, situated on the bank of the Nemunas River, right next to the Winter Port, where ships would drop anchor. Undoubtedly, the factory’s founders, the Šragė brothers, also drew on the symbolic weight of the anchor – an emblem of hope, stability, and success. And indeed, the name proved prophetic for the factory’s fate through all three stages of its existence.

Before the war, Inkaras became a symbol of hope for a better life – and not only for the factory’s workers. It represented a modern leap from traditional bast shoes to locally made galoshes, finally affordable to every compatriot. During the Soviet era, the “inkariukai” once again became a Western dream and a symbol of freedom. Finally, in the 2000s, the Inkaras hunger strike saw its participants hoping to restore justice. And indeed, they not only recovered their earned but long-unpaid wages, but also initiated the creation of a guarantee fund, which later provided financial support to employees of companies that were going bankrupt one after another at the time. All of this could only happen under the sign of hope.

Red Baptism

Inkaras kept its prewar name even after the Soviet occupation, after nationalization, and throughout the entire Soviet era, while its relatives in Riga and St. Petersburg quickly transformed into the Red Square and the Red Triangle. When Lituanica became the Red October, Vilkas (Wolf) howled and mutated into one of the four communards, Kazys Giedrys. Meanwhile, the Silk-Plush Factory – so soft and gentle by name – was crushed under the full weight of Pranas Zibertas, a participant in the prewar communist movement who had spent half his life in prison for anti-state activities and thus built a prison for us all – bringing back Stalin’s sun together with his delegation.

Perhaps the most vivid and moving story is that of the shoe factory Lituanica.

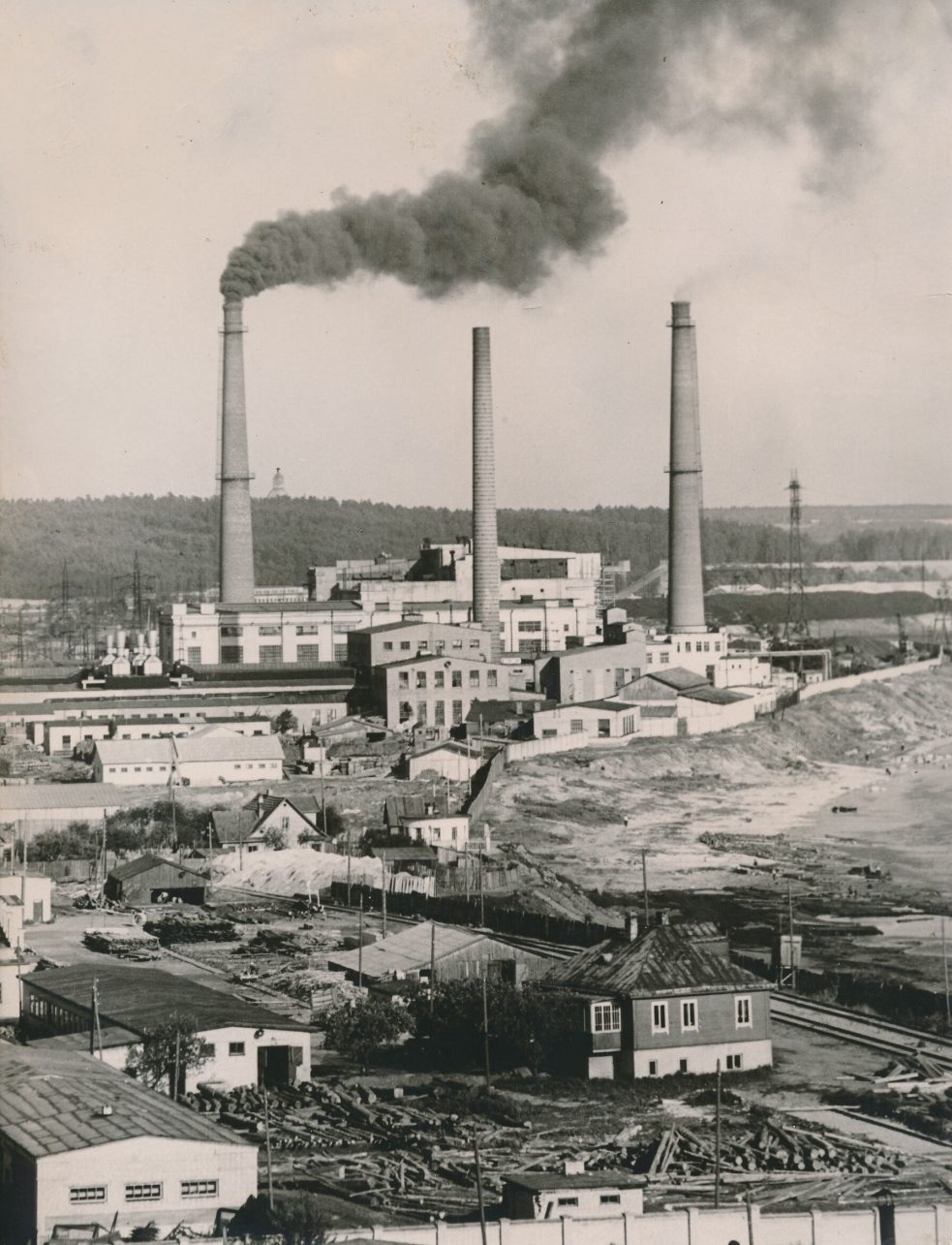

Having received red names, the factories grew like crazy, expanding and enlarging, and inside them the grotesque of a planned economy was brewing – a lot, cheaply and quickly.

The Šančiai Drobė managed to preserve its Lithuanian name and the quality of its fabrics and was lucky with the partorg (the party organizer responsible for maintaining the political climate in the factory, usually Russian). It was the only factory in Kaunas whose partorg actually learned Lithuanian! And yet, the name of Drobė received an addition – a red escort: words – controllers, names – comrades. Like in a parade, four words – as if having jumped straight from the communist vocabulary – lined up around Drobė: labor, red, banner, and order. Until 1989, Drobė’s full official title was: The Kaunas Labor Red Banner Order Drobė Wool Production Association.

A small history of Lithuania

Perhaps the most vivid and moving story is that of the shoe factory Lituanica – a kind of micro history of Lithuania itself. In 1934, the Gothelf brothers, with God’s help (from German Gott – “God” and helf – from the verb helfen, “to help”), purchased premises in the Old Town, on Jonavos Street. After setting up a shoe factory, they decided to name it something deeply emotional and solemn – Lituanica – clearly inspired by Darius and Girėnas’s transatlantic flight. There was some resistance to registering such a name – the public wondered whether it was too grand a title for a factory producing footwear that trampled the ground…

But once again, with God’s help, the brothers obtained the right to use the name for their factory. And they produced, it must be said, excellent shoes. Sadly, the story took a tragic turn. When the war broke out, the Germans were the first to execute most of the factory’s workers (who were Jewish). Later, the Bolsheviks nationalized the factory and renamed it The Red October. Under this new name, the products became synonymous with poor quality and were even mocked in the Aliukai song:

Those are some pretty shoes from Red October –

all made on one last.

And those shoes, oh, how fine they’re to wear

You walk down Liberty Avenue, and your feet pop right out.

It wasn’t because the craftsmen didn’t know how to make good shoes – it’s no secret that the factory’s shoemakers often made excellent custom shoes at home. The real culprit was the absurdity of the planned economy, which prevented any pursuit of quality.

Lituanica was the very first factory to reclaim its original name in 1988, as soon as the winds of perestroika began to blow.

Sadly, it didn’t produce shoes for long afterward – as production volumes decreased, it left its historic premises, and in 2020 it finally went bankrupt. The factory buildings and grounds, though repeatedly promised to be revived by creative ideas, still slumber to this day.

The stolen poet

A double robbery took place when the Kaunas paper factory was renamed – not only was the factory itself nationalized, but by giving it the name of Julius Janonis, the poet was stolen as well. A Marxist dreamer who wrote on socially sensitive themes, Janonis had nothing to do with revolution or revolutionaries – he died at twenty-one, in 1917, before the October Revolution even began. Did the name-givers lack imagination, or were there truly no other Lithuanian communards active in 1917–1918, that they had to resort to Julius Janonis? Did the others not know how to write? A paper factory, after all, is an associate of culture!

Beautiful heroines and lingerie

The communist party wasn’t very inventive when it came to naming, but lingerie factories sparked the imagination of the lecherous. They were assigned the names of eternally young heroines – girls who had died for the ideals of communism at a very young age. The softness of their skin and the firmness of their forms were perfectly suited for manufacturers of stockings, tights, and other stretchable knitwear. After a bit of cognac, the party officials didn’t deliberate long, and in 1958, the Kaunas knitwear factories, merged into a production union, were given the name of Adelė Šiaučiūnaitė. The girl had indeed been an active member of the communist movement, repeatedly detained by Lithuania’s special services, but released each time due to lack of evidence. In 1938, A. Šiaučiūnaitė was found brutally murdered in one of the Žaliakalnis courtyards. The 24-year-old’s death was clearly of a criminal nature, but why not call it “the savage work of fascist intelligence”?

Such a macabrely erotic tradition – the assigning of the names of young fallen communards to hosiery factories – prevailed not only in the Soviet Union but throughout the entire socialist bloc. The youngest “virgin” most likely went to a Zagreb lingerie factory in Yugoslavia. Its heroine, Nada Dimić, died at just nineteen.

Just a warning – when traveling in Croatia, especially further away from Zagreb, it is better not to make jokes about Nada Dimić and lingerie. Josip Tito pampered the Yugoslavs, so even today, the former bloc’s residents are not as intolerant of the era’s heroes as we might be.

Loyalty to the factory name

The factory’s name also extended to the community working there: the Drobė people, the Inkaras people, the Janonis people, the Banga people – not just ordinary Kaunas residents, but proud patriots of their factories. The cauldron of planned economy did not extinguish their ingenuity, and the imposed “red” factory names did not erase their sense of history. Communities measured their factory’s age from the prewar period – the communists wanted it differently, but that thread was never broken. For example, the Janonis community maintained the prewar factory traditions throughout the Soviet era. Founded in 1933 by the Swedes, the factory was known for its modern approach to the workers’ environment, working, and living conditions. The Swedes designed the factory grounds, which the Janonis community continued to cultivate. The tradition of the wind orchestra was also maintained.

In Soviet-era factories, miraculous things often happened, born from the resilience of the communities themselves: wise directors, talented craftsmen, engineers, and designers frequently broke through the “red roof.” Surprisingly, the knitwear produced under A. Šiaučiūnaitė’s name had a distinctly Western orientation – even in the 1960s, they were making artificial leopard-print fur! This seems just as incredible as the 1978 strike by Inkaras workers over impossible work quotas. They refused to rush toward a communist future at any cost. The strike was optimistically reported by the Voice of America. In the Soviet Union, where “everything is for the welfare of the working people,” no one was supposed to know about it.