“The fundamental problem of the real Kazys Pakštas, as well as the character in my film, is the problem of Cassandra. They predict and warn correctly, yet no one believes them, and even if they do, they are unwilling to take any action – the very action whose urgent necessity Pakštas kept insisting on,” Karolis Kaupinis told our magazine in the autumn of 2016, when he was still only preparing to make the film that would eventually be titled “Nova Lituania”.

(The text was published in the January 2026 “Networks” issue of the “Kaunas Full of Culture” magazine)

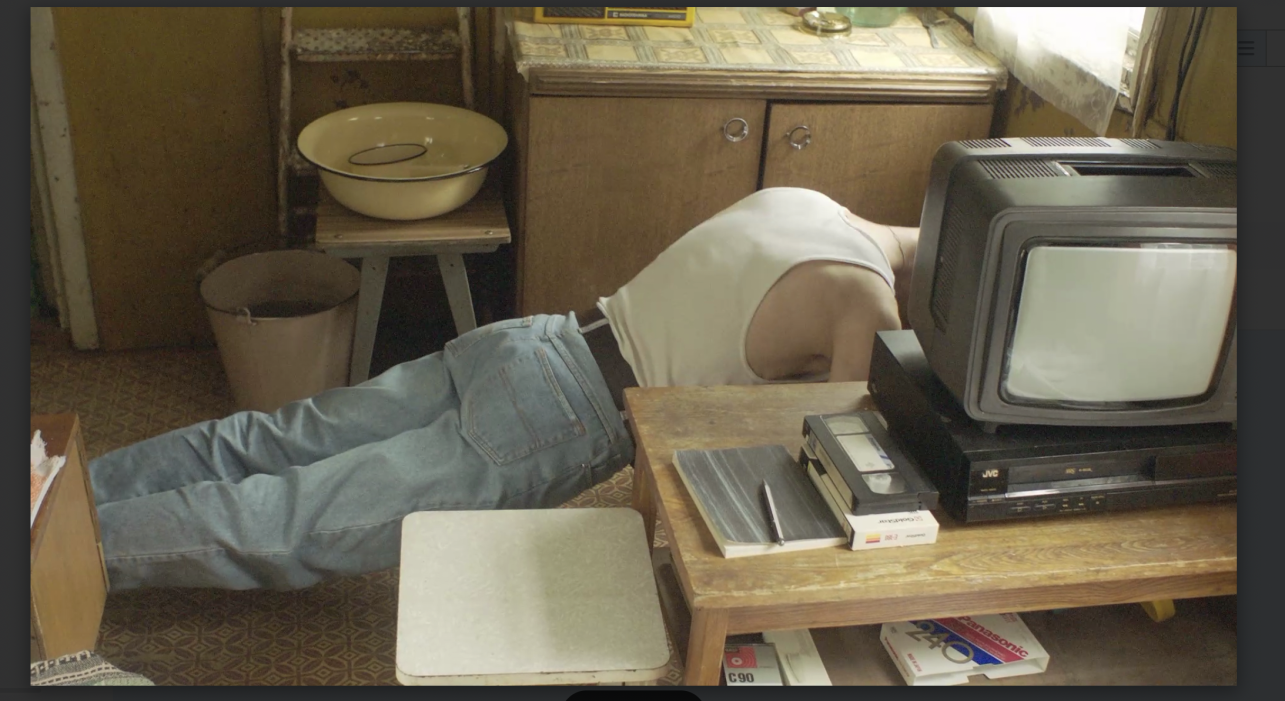

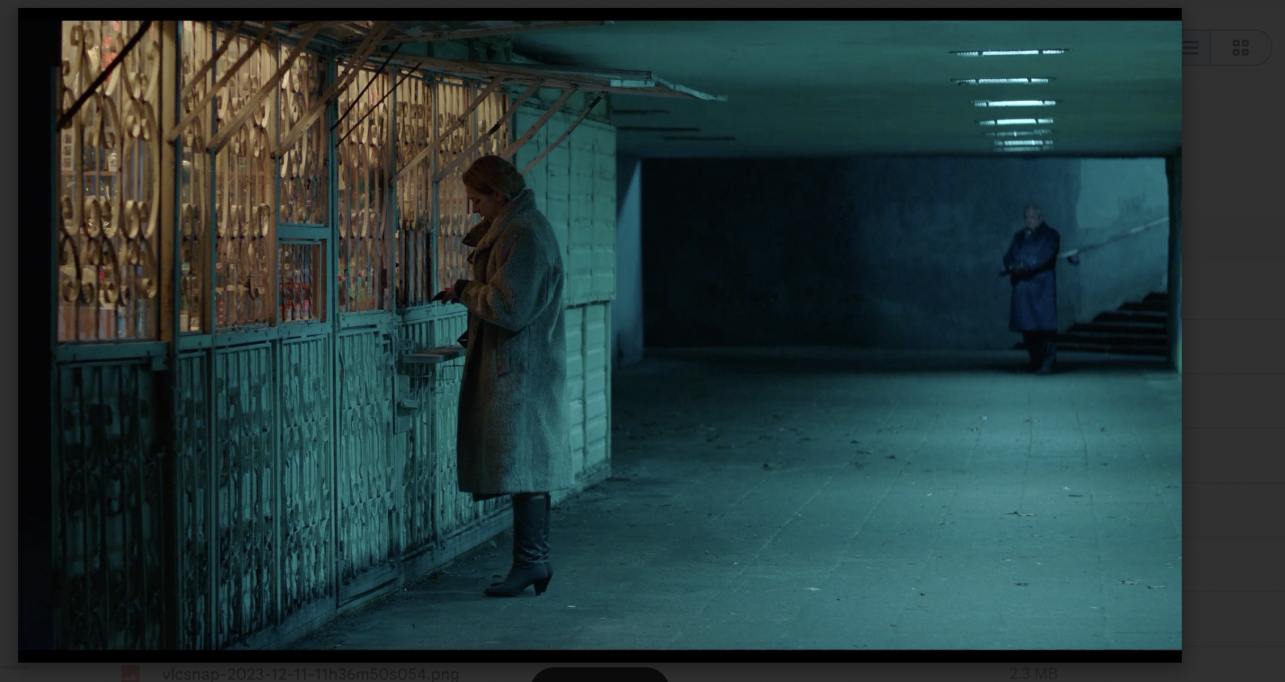

This January, cinemas will see the release of his second feature film Hunger Strike Breakfast, starring Ineta Stasiulytė, Arvydas Dapšys, Paulius Pinigis, Algirdas Dainavičius, Albinas Kėleris, and Eglė Mikulionytė. Although part of the absurdist comedy (with plenty of romance as well) was filmed in Kaunas, in Vilijampolė, the story is set in Vilnius: in January 1991, the Russians seize the Lithuanian Radio and Television building, hundreds of people are cut off from their workplaces, and only one television announcer decides to do something about it. Who joins her? And for what cause?

The story is almost real, and the film, just like “Nova Lituania”, once again comes frighteningly close to reality – much closer than it seemed to Karolis when he finished writing the screenplay. During the interview, we joked that, if one wished, it could even be stretched into a conspiracy theory that everything happening in reality was long ago staged by some kind of reptilians.

Karolis, what were you doing “between the two films,” in other words, what do directors do when they’re not filming?

I taught at the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre. For five years, I directed the exhibition of the Kaunas City Museum’s Town Hall branch, devoting a great deal of myself to it, from concept creation to texts. Then I wrote a play and created audio narratives. And of course, I spent a long time writing the Hunger Strike Breakfast.

Valentinas Masalskis once told me that a good artist needs not only to state the present, but also somehow to generalize and to foresee the future.

At first, the film’s script was about an occupied television station and a propaganda channel set up there, but when the attack on Ukraine began, I no longer wanted to immerse myself in that. I realized I would much rather make a film about people who were on the side of the good guys. That is how I began working on the Hunger Strike Breakfast. I myself worked in television, I knew the real story of the hunger strike very well, had analyzed the details, and knew some of the people who took part in it. Then… then I had children, and that also influenced the script, one of the characters. You try to create, but domestic life tries to suck you in.

We are talking just a couple of days before the protest over the future of LRT (the interview was conducted in the beginning of December, 2025). You yourself are the face of the Cultural Assembly, which led the entire Lithuanian cultural community into the October 5 strike and the events that followed. Your film… You have to agree, you can’t stage coincidences like this. How do you feel and relate to your film that you finished some time ago? Do you think, “Oh, I can write the future”? Did you feel that it contained more meanings than you put into the script?

Valentinas Masalskis once told me that a good artist needs not only to state the present, but also somehow to generalize and to foresee the future. But you can’t do that by simply thinking, “Now I’ll predict things here…” You need to listen closely to what is happening around you and create art that isn’t about you.

I made “Nova Lituania” out of a state of anxiety that I, as a journalist, sank into after the annexation of Crimea. But society didn’t really feel the threats then. To say that the Lithuanian state could simply collapse was tantamount to fantasy. And now, for example, a couple of weeks ago it was screened at a film school – I went to the discussion afterward – and I see people sitting there stunned, because they realize that this is really “how it is.” But that film was made back in 2019. You could say it was too early, but on the other hand, you make something and think – its time will come.

And I see the “Hunger Strike Breakfast” as a metaphor for what Lithuania finds itself in at the moment. When the full-scale war in Ukraine began, in the first weeks, there was a lot of upheaval and involvement, but then everyone started to grow weary and realized that nothing here would be resolved quickly… I thought that the hunger strikers’ hut, which still stands on S. Konarskio Street to this day, is like a parable. Ukraine is our television – occupied, ravaged. On the other side of the street, there’s an apartment block whose residents don’t really care about what’s going on: Western Europe. Basically, we know, we’re watching, but what can you do? It’s not our business. And we – the Baltic states – are huddled together in that temporary hut, fasting. We take action, even though we are not powerful. Will that action bring about a fundamental change? You never know, but you can believe, you can hope.

The paradox is that you desperately seek that togetherness, you want to fill the inner void, but in this world, it is impossible.

Over the past few months, as I’ve been thinking about the film, I’ve realized that I wrote some code in the script – as you say, I took action myself. Of course, it is not very pleasant to write a film script and then live in it. Now I am writing a third one and, well, I don’t want to do it anymore (laughs).

What surprised me was that Hunger Strike Breakfast is not about a united mass, but about individuals. When the film’s characters begin protesting as a group of three, it even looks comical. But after all, every protest starts with not taking the activists seriously. And in the crowd, each of us is drowning in our own loneliness. Were you consciously trying to deconstruct that mythical sense of unity?

First, I spoke with the real participants of the hunger strike; there were perhaps a couple of hundred of them over the course of the action, from its beginning until the August coup. At first, everyone declared patriotic motives: Lithuania, freedom. But once you start digging deeper, you realize that beneath that lie personal grievances and unfulfilled expectations. These are the consequences of occupation: destroyed families, unrealized dreams. All of this exists in my own family history as well. For example, my uncle was an excellent tailor in the countryside. If it hadn’t been for the occupation, he might not have spent his life sitting in a farmhouse with a Singer sewing machine; he might have become a designer. But being a gentle person, when he moved to the city and tried working as a pattern maker in a factory, he simply drank himself into ruin. He couldn’t withstand that horrific Soviet reality. The trauma of occupation accumulated differently in each person, and during the Reform Movement, those abscesses finally burst.

Salvatore Quasimodo’s three-line poem was significant to me when constructing the characters, “Everyone is alone on the heart of the earth / pierced by a ray of sun / and suddenly it’s evening.” People may be in a crowd, but that feeling of being part of a collective formation flashes only briefly. The rest of the time, you are alone. The paradox is that you desperately seek that togetherness, you want to fill the inner void, but in this world, it is impossible. And periods such as occupation simply highlight this human loneliness and deprivation.

I recently visited an exhibition about Balys Sruoga’s Forest of the Gods at the Maironis Lithuanian Literature Museum. On the way out, visitors were asked to write down one word that is essential for survival. I wrote “humor,” following Sruoga’s own logic. But after seeing your film, I would say “dream” as well. Especially in the case of the character Sigitas, a local resident who decides to join the protesters and talks with his parents about their projections for his future and his own expectations. It seems that dreaming, even if naïve, is essential both when thinking about one’s own life and about the state.

I would probably replace the word “dream” with “hope.” The reference to “Forest of the Gods” is a good one. I assume that Sruoga also had hope in the camp. When you have hope, you look for tools to survive that brutal reality. But when Sruoga returns to Lithuania and realizes that nothing will come of it here… Neighbors used to hear him howling at night. At that point, he would no longer have written with that humor, because it was a tool only for as long as he had hope.

I understand hope as the ability to maintain faith, not necessarily meaning that everything in this world will turn out well. It is more metaphysical. Sigis’s dreams may be simpler, but that sense of hopefulness is fundamental. When people say, as the director Mykolas does in the film, “It’s beautiful to dream, but there is reality,” they are essentially trying to say: I have no hope, and you will lose it too. And when you respond, “No – comma – it is possible,” it deeply unsettles them.

Still, you have to train that muscle of hope. This moment is very important for the Lithuanian consciousness. After the destruction of the partisan resistance, in many places in Lithuania, evil did, in fact, triumph. But there are always those who continue to safeguard that hope. They preserve it one by one and pass it on. They are like individual bonfires. The 1956 protest in Kaunas during All Souls’ Day was already organized by another generation. Their parents were broken, but the children took over the flame. They were crushed again. Then came 1972… It always seems as though hope is passed on like an Olympic torch. It is carried by very few – not by a crowd, but by a handful of people.

There is a character in the film who has been sitting by that bonfire for a long time. He looks at Daiva, the director, and Sigis reproachfully, “Where were you when it was needed?” And now, when traveling with the Culture Assembly, I often hear the same thing, “I have been doing this forever, where have you been?” What can you answer to that? I’m sorry, we weren’t there. Thank you for what you did. Now you can rest or join us.

I noticed quite a few cultural references in the film that mean nothing to the current generation or to foreign viewers. “Labanakt, vaikučiai” (Good Night, Children), the poems of Jonas Strielkūnas read by Albinas Kėleris, who has just been awarded the National Prize, “Vidurnakčio lyrika” (Midnight Lyric Poetry) – is that your creative tribute to the time you spent with LRT?

As István Szabó has said, many films about the past are really about your childhood. This is also a film about my childhood. My parents are literature teachers, and poetry was always important to us. The shelves at home were full of books; those names were always on the horizon. So I don’t worry about it too much; someone from my generation or my parents’ generation will certainly recognize them.

Each viewer will take away as much as they want or can. Of course, the film has certain age and geographical limits. I see that it hasn’t really crossed the Berlin Wall yet; the world premiere was in Warsaw. But I go by Michael Hanekeʼs idea that you should make a film about your own village, and then you will speak to the world. He tells his students: don’t make films about Afghanistan, because you don’t know anything about it. Make films about what you have lived through. I personally like watching Eastern European films, for example, Romanian ones, which are not ashamed of the names of their small towns or the details of everyday life. Cristi Puiu’s “Sieranevada” goes on for three hours, and even though I don’t know the entire context, I can see that it’s real life. And if you start blurring those details, afraid that foreigners won’t understand… well, that’s their problem if they don’t know.

The soundtrack of Hunger Strike Breakfast – this light, Hollywood jazz – pleasantly contrasts with the gray reality.

I think music must provide contrast, say something that you haven’t already said with another medium. In good times, you might need dark techno, but in bleak times, something clichéd about love works. If you’re sitting in a sleeping district and listening to Butyrka on top of it, then it’s already a gulag, no hope. Dreamy, Hollywood-style music gives deep anxiety a bottom; it’s part of hope. You can hear the music of Charlie Parker in the film, but we couldn’t afford all of it, so composer Arnas Mikalkėnas and his good friend, New York-based jazz musician Matīss Čudars, made an effort to have the Latvian Radio Big Band perform the soundtrack with Parker’s characteristic freedom.

Another scene that stuck with me is the one where Sigis’s father, when tensions rise, packs his things and drives out to the allotment gardens. That’s such a recognizable form of Lithuanian escapism. During the Soviet era, it provided an opportunity to be freer, to create and feed yourself. But what does that “driving to the garden” mean to you today? Do you need it as a creator, a citizen, and a social activist?

It’s an inner island where you have to retreat to stay sane. The difference is that for a long time, many of us were constantly in that garden. As soon as you sense that something is wrong in society, you head to the garden. It’s good to have somewhere to go, but you can’t just stay there. When everyone is in their gardens, and the city is empty, mad dogs start running wild there. Then you start complaining that the stairwell is messy, the roads are full of potholes, yet you yourself were in the garden.

Now, of course, people retreat into different kinds of gardens: some into books, others into hedonism. For me, that garden is a good text. If I don’t read something detached from reality during the day, it becomes hard. Right now on my table lies “The Small Centre of the World” by Krzysztof Czyżewski, published by Hubris. When you’re constantly colliding with reality, with all the political absurdities, reading a text like that is essential.

And finally, let’s talk about your beloved Kaunas. The film’s press representative suggested interviewing you because part of the scenes were shot in Vilijampolė. Of course, that alone wouldn’t have been enough for me; it was important first to get acquainted with the work itself, but this suggestion gave rise to a question. Kaunas is once again playing Vilnius, just as it was after the Poles took the capital, just as it was after the Russians took over television station. Will it always be like this, or does the city have greater goals?

Let’s start with the film. Kaunas plays Vilnius because Vilnius can no longer play itself. We needed to film the 1991 television, and the current building on S. Konarskio Street no longer looks that way: it’s overgrown with “swallow nests,” renovations, and small alterations. We needed a specific geography: the television station, the street, and on the other side, a non-renovated apartment building. That combination no longer exists in Vilnius.

In Kaunas, we found it near the former Lithuanian Textile Institute in Vilijampolė. That apartment building on Demokratų Street is exactly what was needed, and the institute looks like the television station in 1991. Director Saulė Bliuvaitė, who grew up in Vilijampolė, told me that this building was a symbol of her childhood nightmares – big, scary, half-abandoned… We succeeded – some of the television station staff didn’t even realize that it wasn’t Vilnius.

There was even this meta moment: I recently participated in a Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union drill exercise, where we were training to defend the same television station. The film’s director of photography, Simonas Glinskis, and I were placed at the same specific post that we had recreated in Kaunas based on the photo. We are standing there – I, the cameraman, and the artist – and suddenly we find ourselves in the same film again, only in reality.

And speaking more generally… I think that the relationship between Kaunas and Vilnius is changing. You can’t change the geography: the core of Kaunas is planned on an axis to Vilnius, and Vilnius is arranged on an axis to Kaunas. We are connected. But I feel that Kaunas has finally managed to stop building its identity through Vilnius. And the less Kaunas does that, the more Vilnius starts to envy Kaunas. Lately, I’ve been hearing more and more often, “Why is it that Kaunas has it, and we don’t?” When that happens, the real idea of a twin city is born. One doesn’t just feed the other; they both feed each other.