If there was an election for the most visionary architect in Kaunas, we would certainly see professor Jurgis Rimvydas Palys among the finalists. His works harmoniously fall into the fabric of the city. They are extraordinary but don’t stand out; they are natural as, if they were in their place, but at the same time not neutral. The architectural forms of the small Vilniaus Street that became a visual synonym of the Old Town itself for Kaunas residents; the green slopes of Santaka hotel’s annex, confidently emphasizing the panorama of the historical part of the city; the Aleksotas bridge that turned blue orange twenty years ago; Stumbras warehouse that radiates timely industrial architecture and at the same time echoes the district’s 19th-century birth with its walls. This is only a small part of the architect’s work, which has acquired a physical, three-dimensional form. So only a glimpse into the whole creative energy.

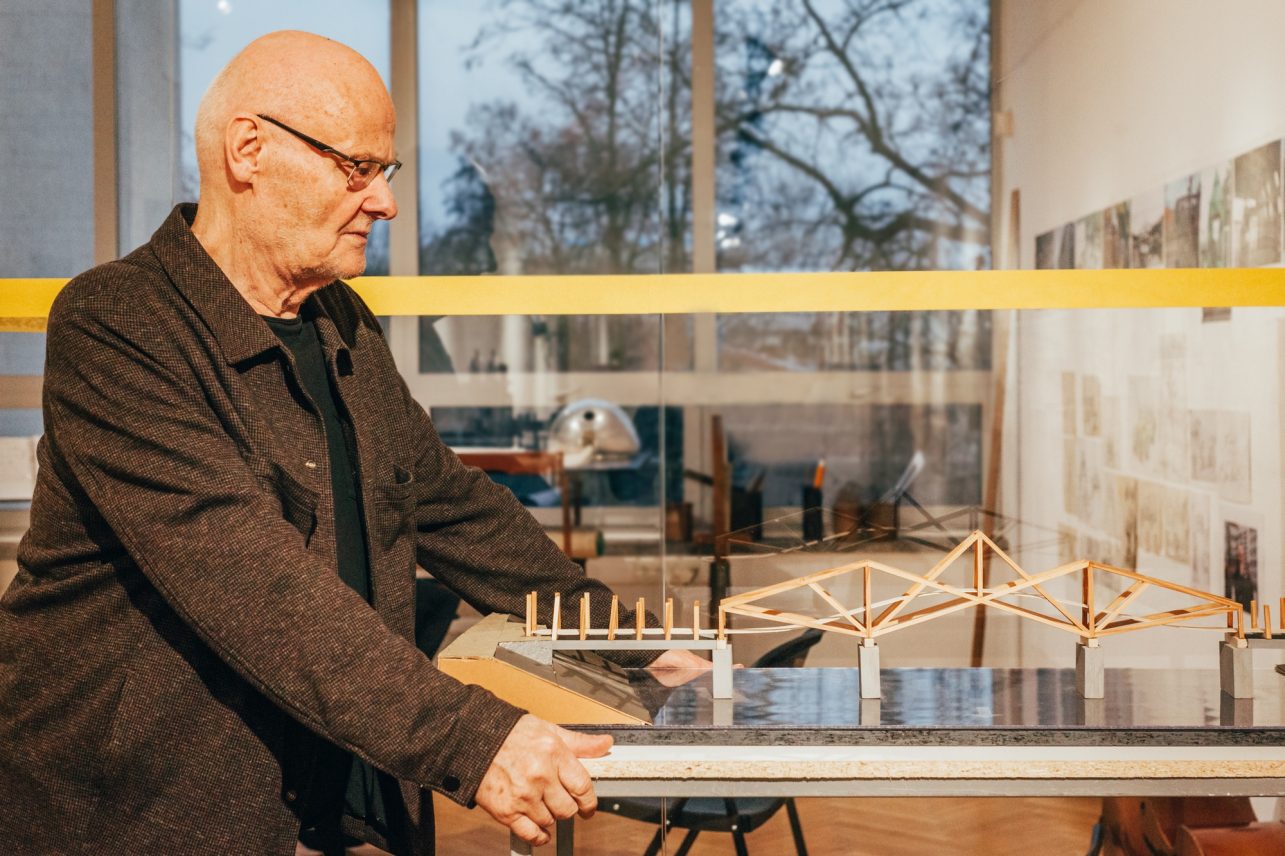

The architect’s personal archive has accumulated an impressive collection of not only different versions of one or the other project but also expressive urban visions for various parts of Kaunas (and beyond), based not only on J. R. Palys’ historical knowledge but also his great ability to sense the city and its principles. Due to the efforts of architect Audrys Karalius and architecture historian Almantas Bružas, the exhibition of the architect’s works and visions Palys’ City. 7 Dimensions of Identity will be open in the Kaunas Picture Gallery until April. In addition to that the exhibition also presents another side of J. R. Palys’ life – his love for exceptional, high-quality equipment, mostly produced in the interwar period. In the midst of the exhibition, I asked the professor some questions about the city, architecture, and himself.

It is said that most architects can be divided into two types – artistic and technical – based on their work methods. Your works often showcase the ability to look at the task creatively, taking into consideration the feeling and history of the place, but at the same time, everything is solved very systematically. How did such a dual style come about? Perhaps, on the one hand, it was influenced by your father, sculptor Viktoras Palys and on the other, it was your own passion for technology.

I sometimes think about it myself, and my friends also say: “How come you are like this and not like that.” My father often said, “Son, I only like pure style.” My whole environment was pre-war, well-designed, Bauhaus-esque – even the teaspoons, the huge Mende radio, modern furniture designed by my father. The publications at home as well: I flipped through magazines about aviation, airships, steamships, and radio stations; I was very attracted to technology. But not for cartwheels and not for candlesticks [laughs]. I have been rummaging since childhood. Once we temporarily lived in a village, and there was a blacksmith working there, who always had a pile of iron near him. I was always there climbing on it. It was full of gears, flywheels, shafts, and axles – I was already drawn to these things. I think, perhaps that is why my architecture is not necessarily techno but close to it, a bit more towards industrial aesthetics. When my daughter Ieva and I designed the hangar of the Military Rescue Post in Aleksotas, I really didn’ t want the architect’s hand to be visible there. I wanted it not to be architecture, but just a good object that would fit near the airfield, near aviation. I often think that almost all architects look at everything through their own prism, and I have repeatedly said: don’t look at your whole life through those architect’s glasses, it’s already creates a certain bias.

Diversity needs to be nurtured, developed, made modern, but uniqueness must also be protected so that the city does not lose its recognizable face.

This attitude was probably also reflected in the knowledge you imparted to architecture students.

I used to say to the students: when you walk down the street, you should observe and question through the lens of an architect how things look, just like a detective sits in a bar and instinctively analyzes people. It is the same with architecture. But sometimes I encourage students to disconnect from architectural thinking and simply look at an object: a river is flowing, a crane is standing, or a train is passing by. Maybe everything is perfect already. Maybe it’s enough and there is absolutely no need for an architect to intervene and start architecting?

I was just recently giving a lecture on this, showing the quays of Budapest and other cities where you can see, as I say, an orderly mess. Wooden poles, moored barges, a train rumbling by, trucks unloading goods, a crane lifts them, and a few simple pubs are open. Slightly chaotic. That’s the whole secret and it’s all the fun! And if an architect comes and tidies everything up, I will become bored immediately. It is dull to walk by glass buildings that a colleague of mine designed. I want to see something that neither you nor I have made, to see what has naturally been done before us.

I can see how those seven dimensions – that became the axis of the exhibition – of Rimvydas Palys are slowly being revealed…

The code of the place is very important to me. It’s such a trendy term now, but it’s true. For example, Šančiai. Those narrow streets branching off from A. Juozapavičiaus Avenue towards the Nemunas like the branches of a tree, those small houses, industrial remains, railway workers’ houses. You can’t just build a five-story house there. If you were hired to build such a house, you must look around, recognize the place and understand what fits there better and what doesn’t fit at all. A city is such a concrete place where you see pavement, facades, shop windows, benches, fountains, and cornices. All those little things create a mood – joy… or not necessarily. Perhaps the architectural or artistic quality of those individual elements is not so important as their very presence, abundance, surprises, angles, turns, and what waits around the corner. All this creates a diverse, unexpected city. Maybe sometimes it is worth looking not only globally, but also in a micro way, for example, if there are no exceptional houses on the street, but there are old trees, and an ancient massive fence covered with climbing plants, perhaps there are several simple interwar period houses. And you feel like in a fairy tale on that street, but you can’t explain why. I used to say to my students: you must notice these things, pay attention, and think about them – they form the fabric of the city, the diversity of the city. As I have said many times, the city is a combination of everything – it has technology and noise, cafes and houses, trees and boats, jazz and silence, noise and… quiet, and old, big ponds with oak trees. Diversity needs to be nurtured, developed, made modern, but uniqueness must also be protected so that the city does not lose its recognizable face.

You designed many of your most famous buildings as early as the year of Independence, but you started your career in design institutes, as was common in those days. Before getting stuck working in Komprojektas for a long time, you had to work in many of these institutions in Kaunas. It would be interesting to hear about the beginning of Rimvydas Palys’ career.

When I finished my studies, I was assigned to work in Lazdijai. But I’m a true native of Kaunas; I would walk around Kaunas built before the war and I adored it. I wondered what I will do in Lazdijai. In Žemprojektas they told me: if you come right away, without vacations, we will take you in. So I got to design the settlement of Duokiškis. Algimantas Miškinis worked at the institute. He was a true urbanist who was broad-minded and understood the structure of all those small towns. I somehow intuitively captured the square of the town, I stuck my own houses in the gaps, which, although modern, had a corresponding structure: sloping roofs, the ends facing the square; I drew the silhouettes. Miškinis really liked it. He saw me and believed in me. This was the beginning. Then I quickly went to Miestprojektas, to which I was invited by Ramūnas Kamaitis, a colleague from Oktava ensemble. He calls Miškinis and asks: so, what can you tell me about Palys? And Miškinis says: talented but a bit lazy [laughs]. Soon they asked me to go to the Institute of Monument Restoration and Design, where I got acquainted with the principles of restoration, restorers, and monument protection. I received a lot of knowledge there. Miestprojektas was, as I call it, all about “box” architecture: regular, correct, square. And Komprojektas had more diversity: a bit of restoration, a bit of new architecture, and their combinations.

Vilniaus street reconstruction project was also born in Komprojektas. What was the design process?

When we had to work on Vilniaus Street, I had an idea – to return the debt to Kaunas. Kaunas is a very small city, compared to European cities, it didn’t have many of the things those other cities had. Neither good squares nor beautiful cobble-stone roads, small forms, pavilions, suspension bridges, or advertising poles. There were almost none of these objects. And I thought to myself: this could be performed. Yes, they didn’t exist but maybe they could have. It’s a bit of a game, but I decided not to do everything in one style. At that time, it used to be that if you designed an object, then the fence had to be of the same style, as well as benches and lamps. As a result, the elements of the old town turned out like this: consciously close to romanticism but at least the phone booth looked like a phone booth, a streetlamp looked like a streetlamp and an advertising pole as an advertising pole. I had designed many different versions of lamps and the ones that are standing now – well, used to stand – were chosen.

Which object did you like working on the most?

In Kaunas, it was probably the small forms of Vilniaus Street. I designed them myself, and I easily managed to coordinate with the chief artist of the city, and then it was a pure pleasure. Everything went very smoothly with the aviation hangar as well. The work with the municipality during the construction of the M. K. Čiurlionis bridge was also successful, and I can only say good things about the city’s chief engineers. But I had opposite experiences as well. For example, Stumbras project. It took so long until I was allowed to speak to the heads of the factory; everything was done remotely… I design something, the project is then returned to me. Finally, I was able to go there and talk to them and everything ended well. Until then, the warehouse itself was just a reinforced concrete frame covered with standard ugly panels. I was offered to do something with it. I proposed covering it with red bricks with concrete strips, to give this strict industrial aesthetic.

The technology collection, if I am not wrong, takes up an important part of your life and probably half of the exhibition. How do you choose what to add to your collection? How did you select the pieces for the exhibition?

What ended up in the exhibition was decided by Audrys Karalius. He told me to bring the things that would confuse the visitors so that they would not immediately realize what they were looking at [laughs]. Yes, it’s an important part of my life, but I don’t call myself a collector. As I mentioned that interest seems to have appeared in my childhood. When I was little, there was a large area near 7th Fort where American equipment left over from the war was stored. Studebakers, Willyses, Dodges, Fords – I was there all the time, from dusk till dawn. You sit in the car, and you can smell the old rubber, and see various devices, and writings. Apparently, I was really attracted to this, and over time, all of this was collected. Objects that someone threw away or gave away to the scrapyard. The first thing that attracts me is the working mechanism. Especially if the item is well made – its shape, and design. For example, this epidiascope. Every small detail and every screw is very aesthetic…

Thanking the interviewer for the conversation, I invite the readers to visit the exhibition. I would like to protect you from bigger “spoilers”, but I guarantee that you will have a memorable experience, looking at the city through the eyes of J.R. Palys; the eyes that are very Kaunas-like and artistically and technically musical. Even the technology collection (called “the machinas” in the style of A. Karalius) is very Kaunas-like. Here you will see the original gong that invited people to the film screenings in Romuva and a sextant used at the Vytautas Magnus University during the interwar period and fragments of research laboratory equipment designed by Vytautas Landsbergis-Žemkalnis. And let’s not forget all the architectural jazz, i.e., sketches. Canals and piers in a humanized, perimeter environment; a glass tunnel connecting the city center with the zoomed-in Nemunas Island and the revived slopes of Freda, the synergy of entertainment and industrial shipping in the old port of Freda, the transformation of the railway station into a terminal that would not put a European metropolis to shame… I leave you with the architect’s words that he uttered while looking at the extensive collection of urban visions on display: “I called these – urban papyruses … I simply drew the way I thought it would look, perhaps detaching myself from reality a bit. How would everything work together, so that the city could get closer to water? … And here’s another version. Sometimes when I get into it, I make one after another, like I can’t have enough. Sometimes I even get sick of myself… well, here’s another one…”

This exhibition is part of the ongoing project “The Year of Palys: 7 Dimensions of the City”.

The project is developed by the editorial team of the architectural e-magazine Pilotas.LT.

Curator Audrys Karalius.

Project manager Almantas Bružas.

The project is partly funded by the Lithuanian Council for Culture.

The project is also supported by the architectural bureaus DO Architects, Kančo studija, Archispektras, Unitectus, ADMA, Bulthaup and the architectural e-magazine PILOTAS.LT.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)