The sun was bright outside the window on Putvinskio Street, the trees were bursting with soothingly green spring leaves, birds were building new nests in their thickets, and in the shade, daily worries were driving people, who were taking their coats off more and more often and wiping sweat from the suddenly dewy brow to different places. The penultimate Lithuanian summer was approaching.

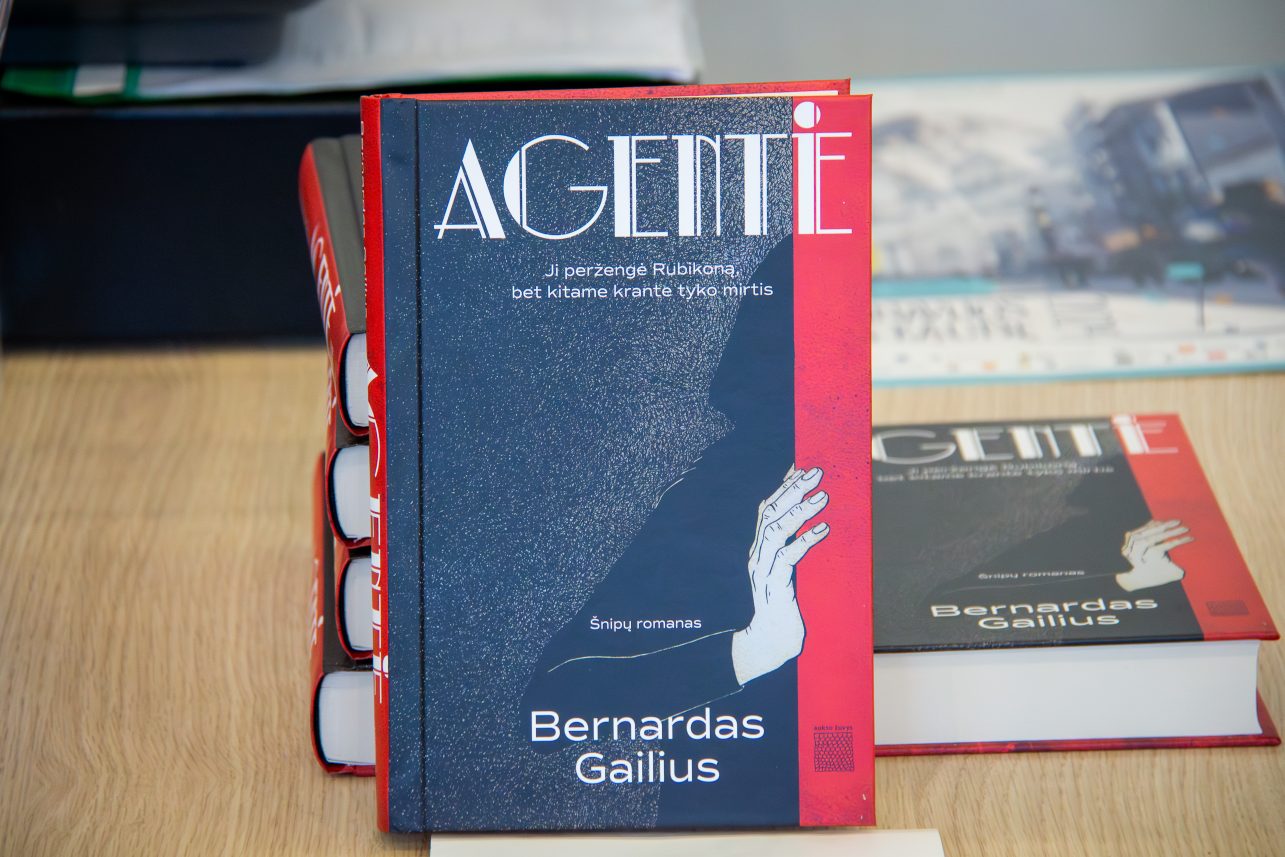

This is a quote from the end of the second novel by Bernardas Gailius. Having immersed his readers in the world of partisans in occupied Lithuania in the first novel, this time, the author invites you to visit the free Kaunas of 1938. It is symbolic that the first meeting with the readers of Agentė (The Agent, currently only available in Lithuanian) in our city took Place on Laisvės Avenue, which was mentioned more than once in this spy novel. It happened this April.

Answering the questions of those gathered at the Vincas Kudirka public library in Kaunas, B. Gailius revealed that the carrot cake recipe dictated to the main character was actually borrowed from his wife. In addition to that, he admitted that there really is a woman named Angelė Treigytė. He had to gift her his new book. However, it is only a coincidence. The events of the novel that was published at the turn of the year by Aukso žuvys publishing house have a historical basis. Similar things could have happened in the interwar period Kaunas, however, the character of Angelė is completely fictional. A fictional young girl with very real problems. What to choose? Communists or America? Konstantinas or Dovydas? The luxury of Kaunas Center or the shacks of Žaliakalnis?

Bernardas, are you a historian turned writer, or a writer, who decided to deepen his knowledge and study history?

It is fairer to say that I am a historian first; at least chronologically more accurate. As a historian, chronology is important to me. Although some of my teachers and editors have told me I’m a writer when I didn’t think so myself. It’s hard to say how much of it is fate and how much is choice.

Your novel Kraujo kvapas (The Smell of Blood) about partisans came out quite recently, just two years ago. Now, the spies. In the past, you have published non-fiction on topics that also appear in your novels. Do you feel like you’ve found your niche?

I have always been interested in what I now call the secret world. These are processes that take place constantly but are invisible to us. As a teenager, I read detective stories, then political thrillers, and spy novels. I have always found that secrecy, mystery, and intrigue attractive. In addition, I studied law and criminology; I wanted to do crime investigations. However, I started working at the Genocide and Resistance Research Center with very specific crimes. There, I got involved in the partisan war research. It contains a lot of mystery.

Was it the mystery that you felt was lacking in Lithuanian literature? It is easy to see that the number of spy novels and their authors is increasing.

I would say that we have the rudiments of the spy novelists’ community now [laughs]. However, Lithuania is still far from the English-speaking world. Of course, it’s nice that we too are discovering this genre, or fiction in general. About twenty years ago, we used to say that there are no good detective stories, romance or fantasy novels in Lithuanian. Now we have everything.

It is time to take a peek at Agentė. 1938, Kaunas. The plot takes us to the streets and buildings well known to the locals. Political opponents are trying to unite to weaken Smetona’s power, and all are working behind each other’s backs. Who was the primary source that led you to imagine how a communist agent played a double game in the interwar period Kaunas?

The interwar period Communist Party has been of interest to me for a long time. It wasn’t my main research object, but it intrigued me as a secret underground organization. No one ever learned what most of their activities consisted of.

First, some foundations of the plot came about. I had the idea that the main character should be an agent, and that something dramatic happens to her but at one point, I ran out of reason: why was it happening? What political intrigue should the action revolve around? I discovered a few articles that were written about the opposition to Smetona, aiming for the division of power in 1938. That part in the book is more or less correct. I had to come up with specific dialogues and meetings myself, but it became a very good backdrop for the story of the secret world.

You have mentioned that you spent a lot of time in the Wroblewski Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences. Is this where the outlines of the Agent started to emerge?

Yes, some twenty years ago I used to go there to prepare for lectures. But, as students well know, that is a tedious work, and because of that boredom, you keep trying to think of some other activity. So, my other activity was flipping through the library catalogue. You open the drawer and see what books are there. That’s how I accidentally found a book that opened the interwar period and the world of espionage to me. It was the memoirs of diplomat Jonas Polovinskas-Budrys. I read it with great interest.

I must say that at that time there was still a great lack of research on interwar period Lithuania. All we had gotten at school was February 16, a photo of the Council of Lithuania, and the Independence wars against Poles, and that’s it. Reading Polovinskas’ memoirs, I realized what an interesting time it was, how colourfully people lived, got along, or didn’t.

Indeed, when reading Agentė, those black-and-white photos of interwar period Kaunas, seen so many times, suddenly gain colour. You describe the style of the characters, the clothes, the accessories, and the interiors of the buildings in a very visual way.

It is a product of imagination. Choosing a city like Kaunas in the interwar period as the backdrop for a story opens up space for more detailed narratives about clothing, food, and other nuances. I must admit that I have been interested in early 20th-century fashion, especially men’s fashion – it helped. In addition, the imagination is fueled by now easily accessible foreign sources: magazines and drawings of those times.

The plot of Agentė unfolds in the center of Kaunas and Žaliakalnis as well as its poor, working-class part, the so-called Brazilka. Today, most of it has been gentrified, with modern houses replacing the authentic shacks. Why did your book need that dirt and darkness?

Partly, the genre itself requires it. The heroes of thrillers or spy novels are often forced to venture into the dark parts of the city and conduct their business there: such is their dirty work. The pleasure of reading comes from the crooked nature of that work. If the character spent their time in a tidy office, the story wouldn’t be as interesting. On the other hand, the historian’s instinct pulls me towards authenticity. If you are writing about an underground communist party and its intrigues, you need to immerse yourself in that environment.

I think I was able to show the city’s multi-layered nature in the novel. While writing, I realized that Žaliakalnis is the best place to reveal it.

And how did you create the characters? Both agent Angelė and those trying to sway her to their side, Konstantinas, and Dovydas, sometimes evoke admiration, sometimes make you want to shake them by the collar, and sometimes induce a sincere pity. Although they are entrusted with important tasks, they are all quite weak, unable to resist temptations. They are just people, after all. Was that the goal?

It is not easy to answer this question and that may be a sign that there is no good recipe for a living hero. I think when a writer tries to create heroes according to a recipe, following advice, that’s when they end up being lifeless.

First of all, you look at yourself. We perceive the world through ourselves and represent it through ourselves. Then you look at the people around you. You see how they talk, how they behave, what is characteristic of them, and you try to apply all this to your characters.

While I was still writing Kraujo kvapas, I made a discovery and memorized it as a rule: the hero shouldn’t be consistent. Yes, the logic of the story might demand it, but this is not typical for people. If a person says one thing, it doesn’t mean they won’t change their mind after a couple of weeks. We promise to quit smoking and then continue to smoke, or we plan to start jogging and then never do. The same principle applies to work, even in dangerous situations. I believe this is what gives characters life.

You mentioned Kraujo kvapas. I wonder how much the success of your debut novel inspired you, or conversely, weighed you down?

Success is a big word. That novel came out fine, I am happy with it and glad that various readers are giving good feedback on it, and – something that I didn’t expect – even the literary professionals recognized it. On the other hand, I knew when I was writing it that there would be another book. I enjoyed the process itself, and the fact that Kraujo kvapas was accepted, published, and read was proof that other people also thought that I was capable of writing. Knowing that others are interested in your work, gives you confidence.

Whose recognition is the most important to you?

The reader is the most important factor for me. I want the people who pick my book up to be unable to put it down. Ian Flemming has said that most of the creative effort goes into making the reader turn page after page, turning that mechanism on.

Agentė finished, but her story didn’t. Will there be a sequel?

I was also asked this after people read Kraujo kvapas. I usually only talk about the novels that will be written and published. So now I don’t have much to tell you, but I really hope I will surprise everyone. By the way, my non-fiction book about the history of Western intelligence services will be published early next year.

Being from Vilnius, how did you see Kaunas when writing Agentė?

I knew that writing about Kaunas was risky and that I wouldn’t necessarily be praised by the people of Kaunas for it. I like Kaunas very much now, although I didn’t have a natural love for it. At one point I was analysing the interwar period press, so I got immersed in that world, I lived in that atmosphere, specific events. When you come to the city after such an experience, you start seeing the city in a completely different way; you realize its geography comes from the interwar period. I never got rid of that image.