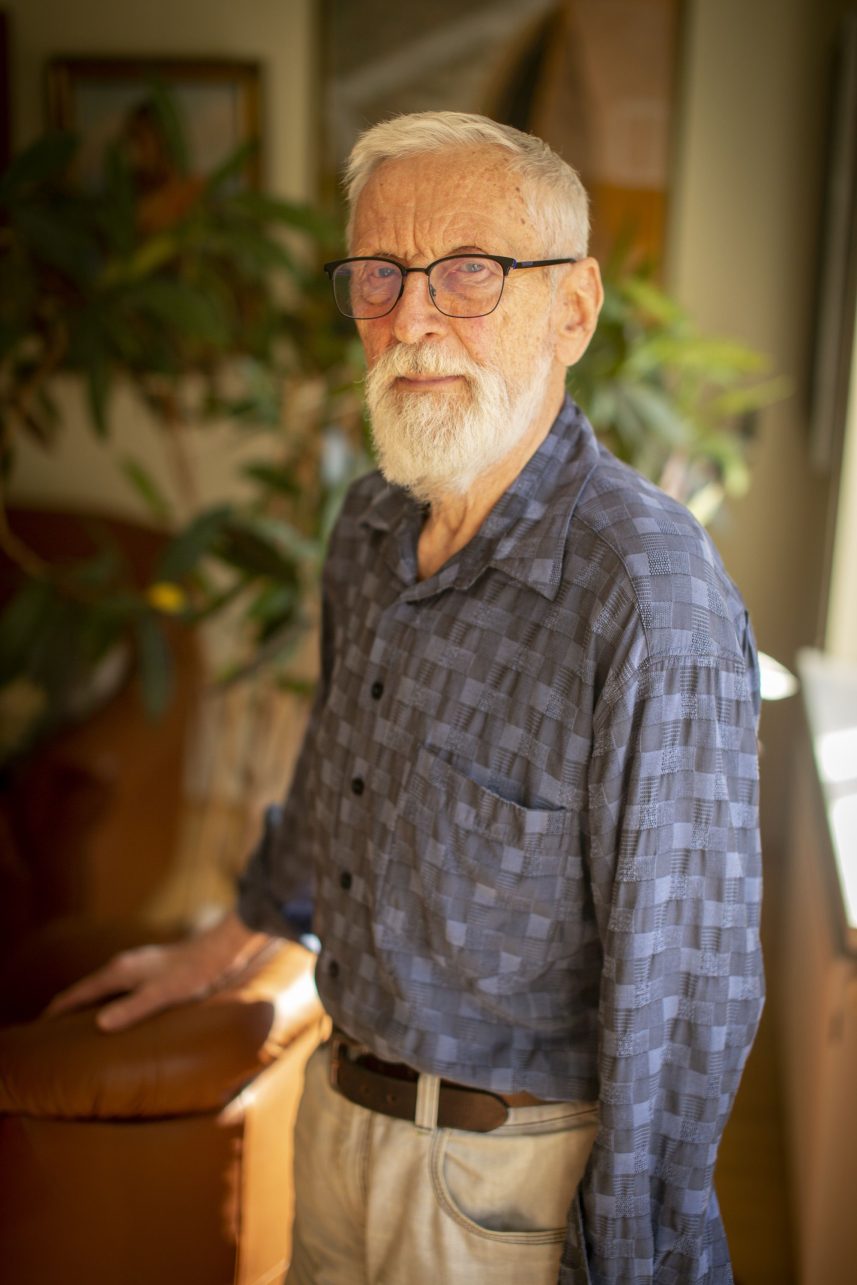

Gričiupis, the smallest district in Kaunas, isn’t widely known, so its location often requires clarification: it’s the area surrounding the KTU student campus. In honor of the new academic year, we discuss this place, which is dear to the thousands who have pursued, are pursuing, and will pursue higher education in Kaunas, as well as the student journey itself, with one of Lithuania’s architectural veterans, Vytautas Dičius. He claims to have left some of his most important and prominent works in Kaunas.

My 94-year-old interviewee lives in Antakalnis, Vilnius, where we visited him. He joined the post-war development of Kaunas in 1956 as an architect at the Kaunas branch of the Urban Construction Design Institute and lived there until 1971.

Both Vytautas and I, sharing names of Lithuanian dukes, were born in an independent, free Lithuania. However, my interviewee was born more than 60 years earlier, in 1930, in Vyžuonos, part of the Utena District Municipality in Aukštaitija. It was there that the architect spent his childhood and began attending school.

“When my father returned from America, he bought a small old manor and 80 hectares of land. The former landowner had left for Poland after receiving compensation from the government. There used to be more land, but after the Land Reform, the remaining one was divided among four volunteers. Now, there’s not a trace left of the Baravainiai manor where I grew up and where my father farmed,” the architect recalls.

V. Dičius’ father returned here after World War I, having served on the western front on the American side. He said he had saved money and wanted to help Lithuania. He brought back livestock, mainly pigs and turkeys, from abroad. After starting to collaborate with local companies, he quickly began exporting his products overseas, expanding the farm and business.

The Path to Architecture

One can easily imagine the fate of more prosperous farmers who owned larger plots of land during the war and the first Soviet occupation. Many tragedies including land nationalization, forced Soviet elections, and deportations began. Vytautas vividly remembers the bodies of partisans that were repeatedly left in the town square by Soviet enforcers, which locals were afraid to retrieve for fear of repercussions.

“The war came, and my days of being a carefree kid were over. My father was sentenced to 8 years in prison. We left our home and went to stay with my mother’s brother. I saw how the Soviet enforcers stole everything. Eventually, I moved to a secondary school in Utena. But they knew I was the son of a landowner, and there was a pervasive sense of discomfort. I relocated to Anykščiai as a landless son, in hiding,” Vytautas recalls with emotion.

Thanks to a good teacher, Vytautas managed to obtain a clean reference, which proved crucial for his admission to higher education. He then moved to Vilnius, where the city made a huge impression on him; he had never seen such architecture before. However, it wasn’t easy, as education during the war was not very consistent.

After considering all the institutes, Vytautas Dičius chose the Lithuanian Art Institute (now the Vilnius Academy of Arts). As he says, in 1949, eight students joined the program, and now only two are still alive. The architect recalls that this was during the active period of the partisans, with the bodies of the forest brothers still falling in the streets of the cities. Among those who enrolled, there was one who left his studies to return to the forest.

Arrival in Kaunas

The architect, who will be known in the future, finished his studies in 1955. He mentions that there was a lot of absurdity: strange Marxist lectures, imported lecturers, and post-war hardships.

“Despite everything, we always resisted one way or another. Especially against Russian architecture. It was foreign to us. I come from a generation that had everything taken away: not just material things but also the best years of life, youth. With that mindset, both I and others grew up combative. And we – this generation of free interwar children, stripped of everything – carried this with us until the Sąjūdis,” says Vytautas Dičius.

So where did he draw inspiration from? There was no internet, no magazines, no Western internships. The answer comes immediately, without pause: the greatest inspiration for young architects was the architecture of Kaunas that emerged during the years of independence. Later, with the arrival of N. Khrushchev, it became permissible to design in a more modern and relevant way.

“My wife was about to give birth, and we had no place to live, so we were renting a small room. Her parents lived in Kaunas, in the K. Petrauskas house. We moved in there as well. In total, we spent about 13 years in that house. I was assigned to the City Planning Institute (Miestprojektas) and started doing regular work. Until then, I had been working in a more administrative and less interesting job in Vilnius,” continues the architect.

It can be said that from this moment begins perhaps the most prominent creative phase of the architect’s career because he starts working with other known architects of Kaunas: Algimantas Mikėnas and Algimantas Sprindžius.

The idea of a student campus

We present his creative biography quite briefly, but it is written about in more detail in Algimantas Mačiulis’ book Vytautas Jurgis Dičius: Through the Architect’s Eyes (VDA Publishing House, 2018). However, for this student-themed issue of our magazine, in our conversation with the artist, we will focus only on the design, construction, and establishment of the current KTU student campus.

Although much of the academic elite of Kaunas either fled to the West or was deported to the East, Vytautas Magnus University continued its activities and, after the reorganization, dispersed across various buildings in the center of Kaunas. In 1950, when Vytautas Magnus University became Kaunas Polytechnic Institute, Kazimieras Baršauskas was appointed as the rector. After the difficult post-war years, the rector took the initiative to create a new academic campus. With the Government’s approval, the Kaunas City Executive Committee allocated a 64-hectare plot in Žaliakalnis. Although much information suggests that the general plan of the plot was prepared by a team of architects, according to the speaker, he personally did most of the work. Within less than a decade, a cohesive architectural complex of Soviet modernism was created. Only the final and largest buildings for the Faculty of Light Industry were left unbuilt.

Choosing the Area

“The plot was chosen intentionally. A chemistry laboratory, formerly part of the Military Research Laboratory and designed by Vytautas Landsbergis-Žemkalnis, had already been transferred for university’s use. Nearby, on Vydūno Avenue, I also found three Stalinist dormitories. The further area was still undeveloped at that time; it was the edge of the city,” Vytautas said.

Before the student campus was established, there were many objects that belonged to the Kaunas fortress in the area between the Girstupis and Gričiupis valleys: batteries, ramparts, culverts, and so on. For example, there were once bunkers and defensive batteries where the current building of KTU’s Faculty of Chemical Technology stands near A. Baranausko Street. The surrounding river valleys that frame the area also influenced the layout.

“Our area was located on higher ground; we didn’t descend into the slopes. Everything, except for the newer buildings, such as the Design Faculty and the current Santaka Valley – projects I didn’t work on – was constructed exactly where I had foreseen in my original general plan. The only things that changed slightly were the building configurations because the exact dimensions were not always known. I chose an open, pavilion-style layout,” V. Dičius continued.

By the way, another student campus started forming in Noreikiškės, now known as Akademija (which Kaunas Full of Culture wrote about in November 2018, ed.) sometime before the KPI student campus. However, the architect says that they did not inspire each other or borrow ideas; examples and inspiration were generally lacking.

There was a shortage of everything, including building materials. There were fears that after the construction was completed, there wouldn’t be enough funds to equip the buildings, and money was needed for laboratories. Despite the poor construction quality of that time, an architecturally valuable ensemble of Western-style modernist architecture was created. It is often mentioned that the ensemble echoes Bauhaus aesthetic, but as the author himself states, it is pure functionalism.

Contributions by the Academic Community

The information sent by the KTU Museum states that a significant portion of the academic community at the institute at that time contributed to the implementation of V. Dičius’ ideas. The initiative began with the Construction Faculty (now the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Architecture, ed.), which at that time was housed in the poorest conditions. It is mentioned that Professor Kazys Šešelgis, head of the Department of Settlement Planning and a specialist in territorial planning, was responsible for planning the area. Faculty constructors were involved in the creation process of all the new buildings, designing them and ensuring they were suitable for both laboratories and lecture spaces.

As was customary at the time, many of the hard tasks were carried out by the students themselves. After their first year, they would document the specifics of the work. After the second year, they would undergo a four-week practical training period where they had to replace construction workers. After the third year, they participated in a seven-week industrial internship, during which the students either worked as laborers or team leaders, and the more talented ones even substituted for department supervisors. After the fourth year, the best students were sometimes placed in the position of department heads.

Legacy

In less than 15 years, Vytautas Dičius left a significant mark on Kaunas. The recently renovated, and in some places reconstructed, buildings of the KTU student campus appear aesthetically resilient and continue to serve their function well. The existing architectural ensemble is continually being enhanced with new additions, the latest being the M-Lab project, which was opened last year and is located on the site of the former entertainment center Kolegos.

The Cultural House of the Artificial Fiber Factory, better known as Girstupis, is located nearby and was also designed by Vytautas. According to the architect, this building is particularly important for two reasons: it featured the first 50-meter indoor swimming pool a shopping center of a type not seen before.

Buitis department store designed by V. Dičius and located on a complex plot near the bus station is also interesting. Although the facade has been altered, the building’s essential volumes and shapes remain unchanged. During the Soviet era, this was a complete novelty: you could buy everything you needed for your home in one place.

Older readers might also remember the interiors V. Dičius designed for restaurants such as Orbita and Tulpė. However, the architect mentions that his most important work was Nendrė café in Trakai, which no longer exists. He said he created everything there from A to Z.