November 6, 1972. This date is engraved onto one of the silicate bricks in a wall that can be found in the courtyard of K. Donelaičio Street between the houses marked with the 72nd and 74th numbers. It should be mentioned that it is only the top of the wall. Below, there is an interwar period layer and under it, the tsarist one. It turns out that in the 1930s it was decided to lower the level of Donelaičio Street, to bring it to the level of Laisvės Avenue, “Like in Europe.” Even one of the wooden houses located in the courtyard, with multiple owners, has a relatively new foundation.

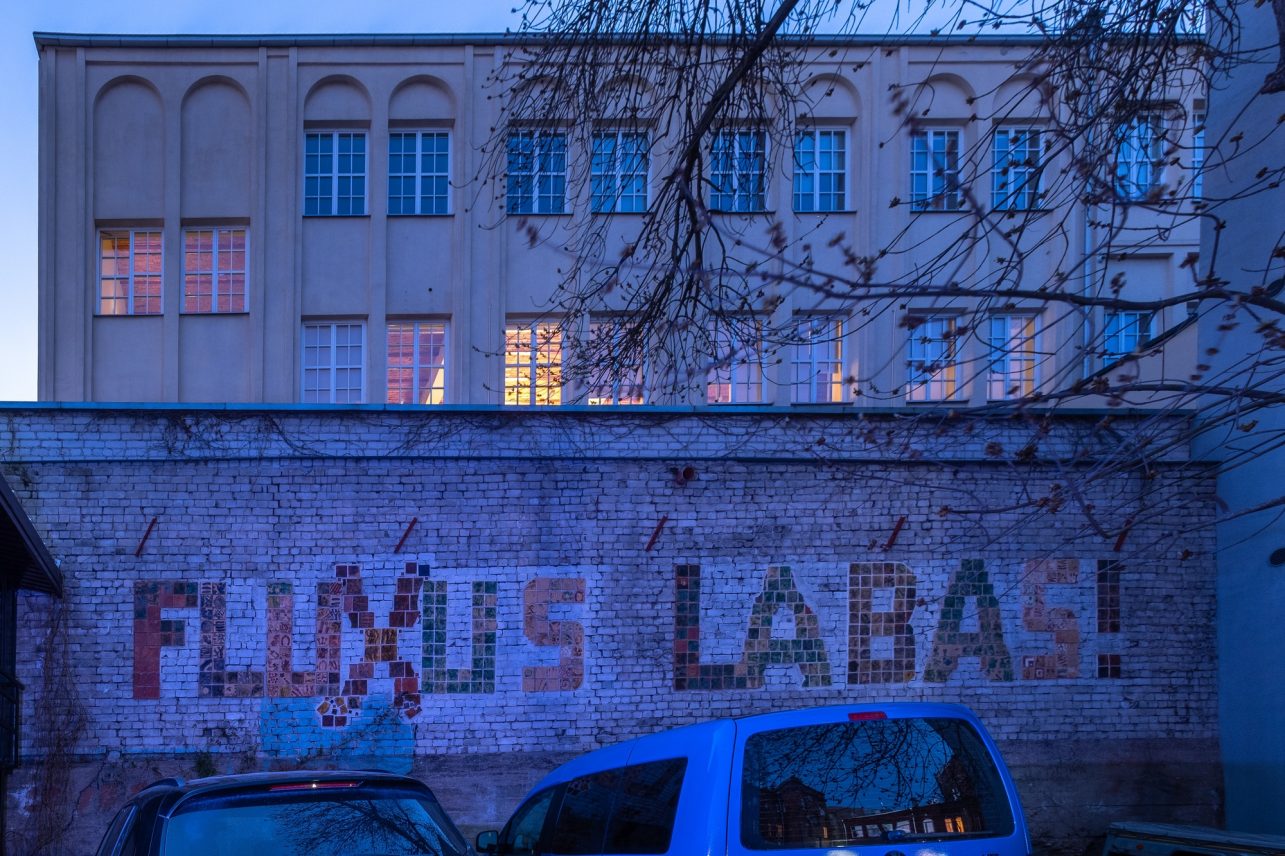

This is how much I managed to find out during the first few minutes of meeting Inga and Žygimantas Šarakauskas. I was lucky to have been able to catch these Kaunas residents – free people, as they refer to themselves – because they spend their summers in a homestead in Lithuania Minor. The aforementioned wall that marks the transformation of the city and which was decorated with a large inscription that says Fluxus Labas! became the pretext for our acquaintance. This is the result of Kaunas 2022 community program project Fluxus Labas! Kiemas. The text is made of several hundred ceramic tiles. Each of them is unique, created by different people, each of them leaving a unique imprint. “We could say that around 300 people were part of this.”

The residents of the courtyard were the first to imprint their palms in the clay tiles (someone also imprinted a little foot, which had grown since and wouldn’t fit the mold now) followed by members of the Kaunas Arka community. Later, during last year’s Courtyard Festival, passers-by of Laisvės Avenue, seduced by the workshop, also made various imprints. And not just Kaunas residents but tourists from abroad. For example, there is an imprint of a pipe from a resident of Marvelė and even am immortalized bee (or a bumble bee?) that stung Žygimantas’ second cousin during the artistic happening. The adjacent tile has syringes in it. They contained adrenaline, which was injected by his sister. They saved a person’s life and thus deserved to get a mention in the history. They were produced by relatives in Šarakauskas homestead, which is visited by many people anyway. “So, thanks to this project, many people – Dutch, German, Jewish, Japanese, Italian – learned about this art movement, i.e., Fluxus, and that it has its origins in Lithuania. It is also world-renowned! We are rather big – a part of the global culture.”

These stairs have a history. They are from the other side of Donelaičio Street. Some people bought the building and decided to demolish everything and build something beautiful instead.

According to Žygimantas, this writing on the wall is very much a Fluxus kind of thing, “Everything a person does is art, and there is no need to worry whether others will understand or consider it art.” “Or that you failed at it,” Inga adds. “Professional artists worry if the result will be evaluated with money and Fluxus artists don’t even bother. Everyone, who has been involved in this event are Fluxus artists,” Žygimantas is convinced.

Interestingly, the couple doesn’t even see the writing on the wall from their house. It is best seen from another courtyard, which is separated by a small threshold. But truth be told, morally, the threshold is higher. They are not on very friendly terms with the “other courtyard”. According to my new acquaintances, the “others” were laughing when the writing was being created, suggesting that they could have at least put plaster on those silicate bricks. Apparently, they found it ugly. But it was this and not that courtyard that became the Fluxus Courtyard. “We think it’s beautiful out here,” Žygimantas says.

The wall is not plastered, but there is a date engraved on it, a bluish area, a witness to the former shed. There are also writings left by children who had grown up since. Later, there will be grapes, they will enjoy the constant exposure to the sun. It turns out that the grapes – forty plants – were grown by Jews who once lived and whose life stories were cut short by the Holocaust. Inga and Žygimantas calls this wall a “wailing wall.” According to Žygimantas, the multiculturalism of each city should not be forgotten, “Such is life. The story is tragic. The residents were taken to the Ninth Fort, and they did not return. Over there, where the cats are sitting, the first bicycle shop in Kaunas was located.” The gates to the courtyard were wooden. Now, only one small detail decorated in ethnic patterns remains. By the way, talking about the ethic motives. Žygimantas told us that lilies and other treasures found, for example, on wooden chests, were painted by Jewish merchants. “It belongs to all of us,” the interviewee is convinced and immediately draws parallels between that and our concern for Ukraine because it is about people that we consider our own.

More artistic inclusions might be appearing here soon. Žygimantas mentions an artistic action at the entrance to the yard. You might soon find mobile constructions near the Fluxus wall, where city dwellers, who accidentally discovered the courtyard can sit down. Aren’t they worried that the number of tourists will increase? The interviewees claim to have considered this and if they had this type of fear, they would not have created the writing on the wall. They mention the nearby Courtyard Gallery, as a positive example. It is open 24 hours a day and it can be seen from the street. “We are not as attractive yet, meanwhile, the gates on Ožeškienės Street, look very inviting, as if beckoning people to come in.”

“You know, these stairs have a history. They are from the other side of Donelaičio Street. Some people bought the building and decided to demolish everything and build something beautiful instead,” Žygimantas pulls another surprise out of his pocket, pointing to the construction of the outdoor staircase of his home, which probably dates to the tsarist period. Twenty men from the A. Martinaitis Art School, where Žygimantas, a third-generation Kaunas resident, worked, helped to transport a third of those decaying stairs (of course with the blessing of the Department of Cultural Heritage) across the street. He has lived in this yard since about 1977 and likes to joke that he flowed here down the river from Freda. He is the oldest inhabitant of this courtyard!

The current neighbourhood of this yard is solid, in fact, as if reinforced by this artistic project, the course of which helped to solve or push aside the less important life issues. It seems as if the Fluxus kiemas ad appeared precisely on time. The tasks were divided: some people were working on the idea, some handled the paperwork, others were involved with dissemination and yet others with security. Neighbours gather on Fridays (except during the summer) to discuss all important issues. Of course, they celebrate Easter and other holidays together. “So, if you are suddenly out of salt, you have someone to borrow it from?” I ask. “We don’t go to borrow some salt, we go to have dinner,” Inga laughs.

You should also drop by, but not to borrow salt, of course. Come by to explore and guess what’s encoded in hundreds of Fluxus Labas! tiles. Carefully, without stepping on the tulips, sit down on a wooden chair welded to the manhole cover. Repeat.