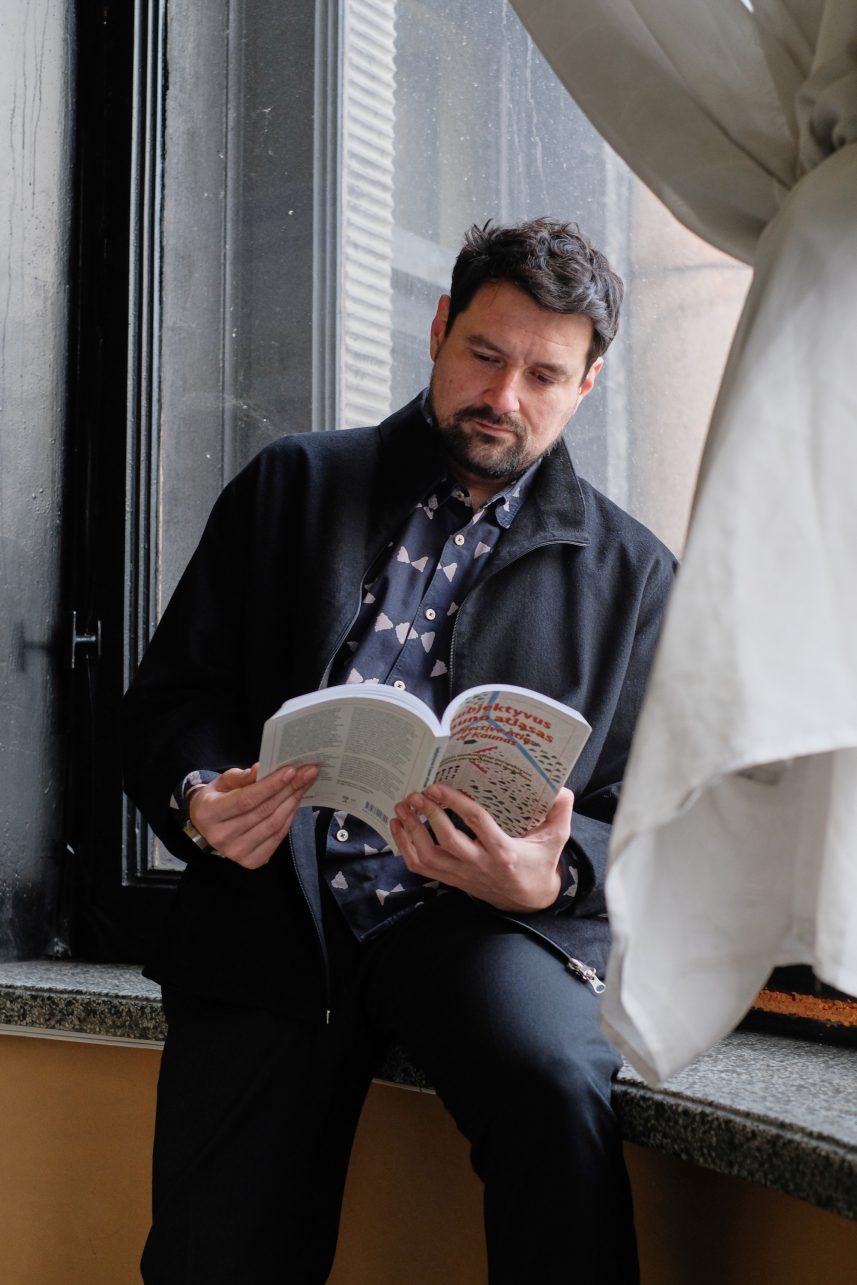

How to grow seven times in twenty years? One must be Kaunas, a city that stood in for the capital of Lithuania between the two world wars. One of the most recent, highly variegated initiatives that bring this period to life is the publication “Subjective Atlas of Kaunas: Contemporary Perspectives on Modernism”.

Hugo Herrera Tobón, a Colombian-born artist, curated the project currently on exhibit at Kaunas Central Post Office. Hugo joined the team creating the subjective atlas series when it arrived in his home country. Seventy artists worked there for three years – the Colombian atlas was published in 2015. Garliava, an eldership in Kaunas district, where Hugo visited in 2019, already has a subjective publication about itself. This was the first time that non-professional artists created an atlas. And the most nimble ones managed to get the Kaunas-modernist one for Christmas, too – the rest of you should stop by the exhibition MoFu 360/365 for your copy. This atlas includes cats in modernist courtyards, alternative flags, street names, round windows, even building scars – and dozens of other ways to see or hear your environment in a very personal way.

We first talked two years ago when you were working on the subjective atlas of Garliava. And how are you now?

I actually think the Garliava project was very beautiful and quite successful. I felt that the community was very engaged with the project that concluded an exhibition in the TV tower in Juragiai. The tower also has this fascinating history about the independence of Lithuania because they were actually transmitting from that tower in 1991 as Vilnius tower was occupied at the time.

It’s typically not an exhibition space, so it was pretty challenging to make the exhibition, but it resulted pretty well. We could occupy all the office space, which was a bit abandoned. For me, that also added an interesting texture to the exhibition. Then we just put a lot of prints all over the hallways and in the different rooms that we had. We also had this nice DJ making some live music with old machinery from the Soviet times, creating some soundscapes. It was very nice, very celebratory; people were very emotionally engaged.

Then, shortly after that, a new invitation came from Kaunas, this time to work in the Modernism for the Future program, and then start developing this Subjective Atlas of Kaunas with the perspective of modernism. In December, I came back to Lithuania, I did a presentation, which led to the more formal invitation. Then I actually decided to move to Lithuania.

In February 2020, I moved with the idea to start the atlas in April, but we all know what happened in March. Mid-March, COVID broke out, and it was disastrous. All the plans of Kaunas changed and a lot of also bureaucratic stuff, so that delayed the whole process. Ultimately, we started only working properly, doing workshops in October. Then we did an open call, and it was this second wave of COVID, so the idea that I was going to go to Kaunas to the workshop, but that never happened because it was not possible.

It was not safe enough to go and do it there, gather all these people. We had to reinvent the whole new structure and a new way to do the project, basically, for assistance for the community and creative contribution. Then we created this in-the-cloud environment where we would store all our files and information and material. Then I started doing the workshops online via Zoom. Sometimes around 10 participants, sometimes a bit more, sometimes less.

Then those were followed by one-on-one meetings with all the participants, again on Zoom. The methodology was a bit similar, but of course, it’s very different when you work online than when you work physically. That was quite challenging, to be honest. I think we all got digitally intoxicated by the whole thing because it was too many computers and screens, and all the material was online.

Somehow it was a good start, and then we already had a draft by March 2021. Finally, in summer, as things were a bit more relaxed, I managed to go to Kaunas and then do a whole month of residency. Then I could actually have personal meetings again with all the residents. We already had an advanced draft to work on. Then that draft started to evolve into more finalized material.

Can you briefly tell us where you usually start?

The methodology is pretty much the same. I start giving people some exercises that start detonating some memory and identity meanings and consistently trying to go from this bottom-up and personal perspective.

Not trying to imprint an agenda on them or a view on Kaunas, but more simply suggesting and letting them think and start connecting with their emotions and how emotionally they feel connected to the city. I put some strategic questions to try and start understanding how they use modernism, how they see modernism, how they perceive it, do they live in a modernistic building or not, is it something they think about in their daily lives or not, so on and so forth.

Then, I started gathering and mapping all these stories. In total, it was about 40 contributors. Then we started refining the data. We had architects or designers or photographers, professional people that could deliver quite professional material. We also had people to help visually elaborate the material in other cases. Then was a lot of editing time and Photoshopping, designing, layouts, etc. The whole month in Kaunas was very intense.

Then we started to come to a final set of contributions or stories, which led to a draft of 260 pages. Then we made a final selection of around 190-something pages for the book. We managed to conclude the book somewhere in autumn, and it was delivered just before Christmas.

When you arrived last summer, did you find the kind of Kaunas that the participants of the Atlas Workshop talked about in the Zoom meetings?

First of all, I think I already had a perception of Kaunas from the Garliava Project. Even though I was working primarily outside of Kaunas, I stayed in Kaunas and still explored the city a little bit. So, I could recognize most of the participants’ contributions.

Of course, in this project, what is also essential and is always interesting, is that you have to connect with this more intimate, domestic, emotional space of people. It’s not always so much about describing a building, but it’s explaining how you feel about that building, or maybe we’re not even talking about a building at the beginning. We are talking about how you feel, about something more in general. Then I start to bring you to, “Okay, if you have to look at that in the city, where does that feeling belong?”

Maybe they say, “I can connect it with that building, or with that street, or with my own house, or with that park, or with my appreciation for nature, or the Botanical Garden.” Many examples come, so I guess it’s a way to observe a country or a city or a place, but then it’s almost like you start from here (points to the bottom of the screen – ed.), and then you end up here (points to the top of the screen – ed.). It ultimately becomes a review of the entire city.

The mappings many times come from many different places. People mentioned food, objects, personal collections of things at home, or the grey colour of the buildings of Kaunas, and we make a whole story about how grey it is, or sometimes it’s about the length of the streets, or differences between Soviet, and interwar modernism. Every story is very particular, and I think that’s also the richness of the project.

Do people like the grey facades?

There’s a woman who loves the greyness of Kaunas, as it brings her back to her childhood. She comes from a family that was deported to Siberia. They managed to get back to Lithuania when she was a little girl, and her mom had to take care of all these documents in the municipality of Kaunas. She was always left for an hour or so to wander around the streets in the centre of Kaunas. For her, the greyness is authentic.

I think it is nice when you come from this more emotional or memory or identity aspect of things because then you acquire things in a different dimension and when something that we might think like it’s a bit ugly or boring, you twist it around, and you see it from that perspective. It acquires a new value or a new relevance.

Professionals from architecture and related fields were also involved in the Atlas workshop. Is there a significant difference between their perception of the environment and that of ordinary citizens, so to speak, in this context?

Yes and no, because we’re always coming from the emotional side, and I always try to first go to their attachment, like personal-emotional attachment, which brings up the story. Of course, there are some architects who are already guides of modernism, or we also work with Gintaras Česonis, head of Kaunas photography gallery – I think the difference is that they can express a concept or an idea much more visually, or they have more the tools to do that.

Sometimes this point of view becomes a bit sharper already from the beginning because they can submit pretty sharp images. In terms of stories, sometimes you also get fascinating stories from people who may not have the means to express them visually so clearly or send pictures that might not have the best quality.

Kaunas modernism is very authentic, very Lithuanian, and often elements of old folk art and national costume can be found in the architectural solutions.

The story is still the story of the person, and I think the difference is more in that, while the level of stories varies a lot, they are all very valuable and relevant. For me, that’s also one of the most exciting aspects of the project. In the process, I always remind people that the most insignificant or kindly insignificant things are significant or invaluable because we all see them differently.

Kaunas for you might be this one tiny thing that you think is very small. Small discourses also become universal macro discourses when you talk about your identity or when you talk about how you behave in a place. I think it’s all valuable material.

You and your colleagues have published over a dozen subjective atlases. Is this one more architectural, or is architecture inevitable when discussing a place in general?

I think architecture is always inevitable. Atlas is always touching upon architecture, and architecture may also be perceived very wide. Architecture is the urban landscape, and architecture is the urban planning, and architecture are the buildings, but architecture is also the domestic spaces of people. Architecture is also your living room, bedroom, bathroom, or kitchen.

Architecture is also a lot of historical layers, especially in European cities, and architecture is 20,000 other things. I think there is always touch on architecture. The main difference, in this case, is that indeed because we were working specifically with this curatorial program of Modernism for the Future, I did propose the subject of modernism more specifically to people, to reflect upon it, but also I wanted to keep discussion very open.

I also invited people who dislike modernism to dislike it, or people who were uninterested in modernism to be uninterested, or people who ignored modernism to be ignorant about it, or people who are passionate and love modernism to love it, or people who have a solid opinion about it, also to have them, because I think that’s the only way you can also create a bottom-up mapping perspective of a place.

You always have to let people feel and be how they authentically are. The invitation and sometimes the challenge, but the beauty of the project is also that you have to try to connect as much as possible with people at this level so that they come up with the most authentic and visceral perceptions. Then from there, we start mapping all the stories.

And why do those who dislike modernism dislike it?

For example, an artist that we worked with finds modernism quite pretentious. For her, it’s not a thing to adore. She finds it materialistic and something very formal; she’s not very connected with it. She works from a much more expressionistic way and, her reflections are almost a bit ironical about it also sometimes, which for me is also a very valid position.

One of her contributions is actually about the Kaukas stairs, which are inherently part of the modernistic history of Kaunas. Still, at the same time, she was more interested in the mythological aspect. We could map the stairs as something that has a story in the modernistic heritage of the city.

The international exhibition “Modernism for the Future 360/365”, which includes this atlas, runs until April. Can we also find stories about the post building in the publication and the exhibition?

I don’t think there is one specific story in the book that only talks about that building, but the building is mentioned in many different points (on one route from bar to bar, the post office is right at the halfway point – ed.).

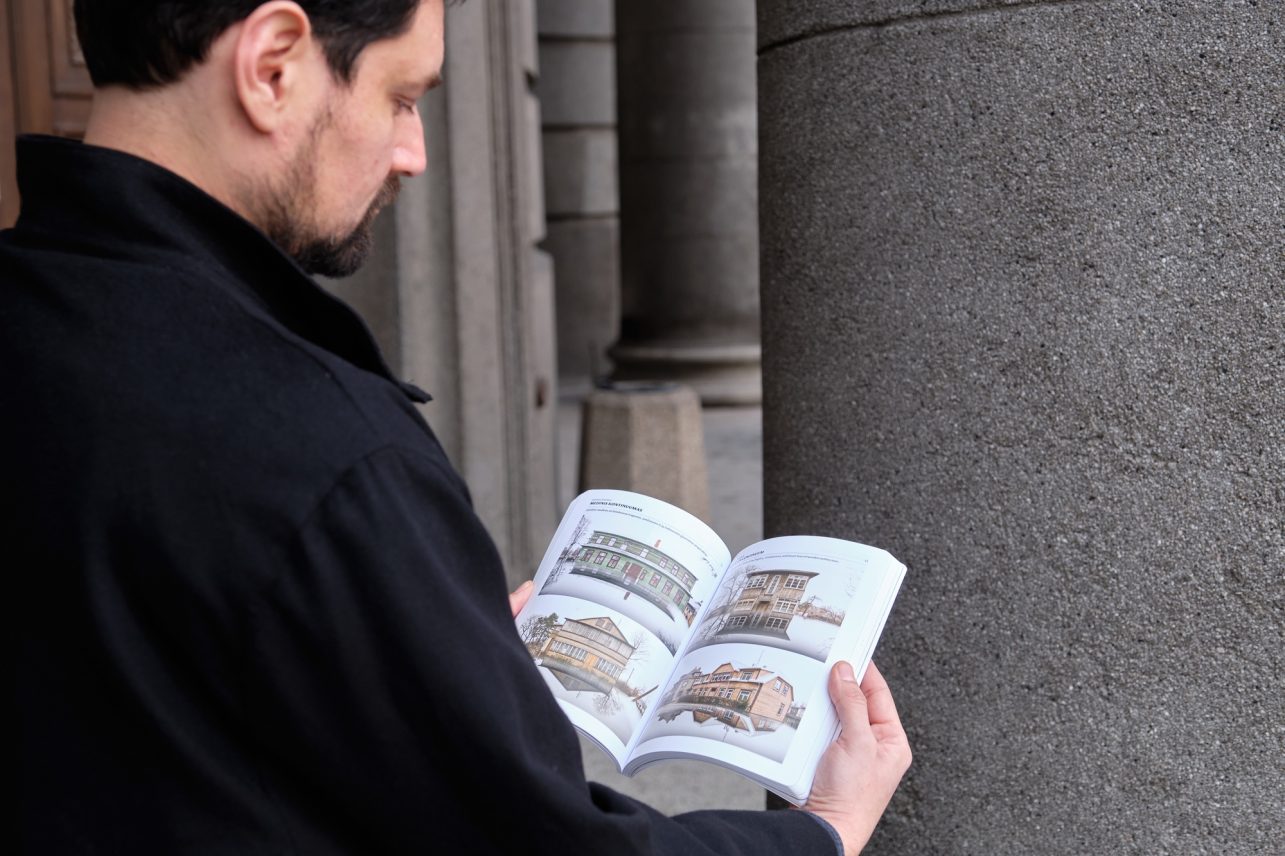

For example, one story is about how fast Kaunas developed between the wars; how fast architects and builders worked to create the temporary capital. The author and I noted that construction was active for about 15 years, during which time the most magnificent buildings of Kaunas were erected. The twelve of them (including the post office) included in the itinerary represent a total of 110 245 square metres! This scale perfectly illustrates the importance of this period of Kaunas and its architectural heritage.

And the floor of the post office has become part of the visual narrative of local modernism. This is very interesting because we often think of this movement as very international, European, minimalist, lacking decorative elements and other distinctive features. However, Kaunas modernism is very authentic, very Lithuanian, and often elements of old folk art and national costume can be found in the architectural solutions. They are found in tiles, floors, doors and walls.

Did you know that you can even buy socks with a postal floor motif?

Really? Nice. Maybe I can get a pair.