Life keeps bringing me back to one of Kaunas’s most famous postcard-like landmarks: the garden of the Vytautas the Great War Museum, the main historical memorial of my beloved city, a pantheon, and a gathering place. Only this time, the focus is on the rear wall – the book smugglers’ wall. It bears only 100 book smugglers’ names, originally carved under the supervision of architect Karolis Reisonas. Yet it encompasses so much: from printing houses in Prussia to the docks of the Nemunas River; from parishes of Pakaunė to the Kaunas Seminary.

But were there really only 100 of them? And what was Kaunas’s role in the fabric of this historical period? We speak with Kęstutis Vasilevskis, communications specialist at the Vytautas the Great War Museum, search for literature, and try to clarify these questions.

(The text was published in the January 2026 “Networks” issue of the “Kaunas Full of Culture” magazine)

When we hear the word “book smuggler,” we usually think of Lithuania Minor, a burly Vincas Juška with a staff in his hand, secret schools in villages, river fords, and forest paths.

The myth that book smugglers were merely profiteering contrabandists is still persistent and very convenient for one side of history.

An urban image, at least for me, would hardly come to mind when thinking about this UNESCO-recognized phenomenon unique to Lithuania. Yet Kaunas was not merely a backdrop. Rather, it was a junction whose significant role was determined by a historical barrier – one known even to the world’s greatest armies – that for a long time also served as a state border: the father of Lithuania’s rivers, the Nemunas.

Juozo Zikaras’s sculpture “The Book Smuggler” (1939). 1961,

Photo by Stanislovas Lukošius. Kaunas City Museum / KMM F 3726

According to the interviewee, “It may not have been an active war, but it was nevertheless a form of resistance – a war in the broader sense of the word.” It is no secret that logistics plays perhaps the most important role in the war, and Kaunas’s role was precisely that: infrastructure, conspiracy, distribution, and allocation.

Book smuggling 101

From 1864 to 1904, the tsarist Russian Empire banned Lithuanian publications in the Latin alphabet – their printing, import, and distribution. This was one of the most painful consequences of the uprising against the occupiers. It was not merely a ban on printing, but a deliberate political measure whose primary goal was the Russification of our nation.

There was nothing romantic about it. Constant risk, persecution, daily improvisation, a life lived in fear, secret caches, long journeys, ever-harsher punishments and… many will find it unexpected or even amusing, but little money. The myth that book smugglers were merely profiteering contrabandists is still persistent and very convenient for one side of history. Yes, there were such cases, but the activity was not sufficiently profitable.

The freedom to think and to express one’s thoughts in the language taught by one’s parents was worth even exile.

Sources note that many book smugglers also engaged in ordinary work alongside this activity. Their meager earnings are illustrated by Vincas Juška’s wooden staff, which in no way suggests a modern or rich life. Moreover, the people who bought these books were not wealthy either, so books and newspapers were read cover to cover and passed from hand to hand.

A cauldron on the riverbank

“The role of Kaunas and Pakaunė during the era of the book smugglers was significant. The city itself resembled a cauldron,” historian Kęstas says. He reminds us of the city’s multilingual character: widespread use of Polish and Russian, a large Jewish community, and an urban way of life in which the Lithuanian word was not common. Yet here lies the paradox: the city was not fully Lithuanian, but the need for the national word was strong.

Another layer was control. It was at this time that Kaunas became a first-class fortress of the Russian Empire. Thousands of soldiers were stationed in the city. There were large garrisons, high-ranking officials, many watchful eyes and constant supervision. Nevertheless, logistics found its own cover. It is no secret that where there are more people, there are also more opportunities to make deals, pay someone off, and disappear into the crowd.

One of the most memorable examples clashing with the image of the book smuggler I had in mind is the route along the Nemunas River from Tilsit, Jurbarkas, or other towns. It is recorded in the sources that the books were transported even by steamboats as far as Vytautas Church, and there, despite the frequent inspections, were people who helped remove, hide or simply keep the illegal cargo out of sight.

Another example comes from an 1886 report by the Kaunas chief of police about distributors of prohibited publications. It states that during a search conducted at the home of Mykolas Simonanis, the officers found books in Polish and Lithuanian. The police conducted the search after receiving information that M. Simonanis was selling banned publications near Kaunas Cathedral. It is believed that he was punished with a fine, rather than being exiled or imprisoned.

It is known that one of the most famous Kaunas residents, J. Tumas-Vaižgantas, also visited this distributor’s shop, albeit later. His testimony best describes Kaunas’s status in the fabric of book smuggling, “Thanks to this [M. Simanonis] and other book traders, Kaunas was a wholesale warehouse for Lithuanian books, which were transported from here to the Vilnius region, Aukštaitija or even deep into Russia.”

Intermediate stops in Pakaunė

Book smuggling was neither the work of a single hero nor it relied on a single route. Kęstas states plainly: it wasn’t so that, say, Martynas Jankus, one of the most famous printers, simply brought books directly to Kaunas. There were intermediate transfer points on the Prussian side; then someone in the coastal region would carry them across the border, and afterward they would be transported further by steamboat or overland. The entire chain was decentralized so that no one could trace it.

If Kaunas were a junction, then Pakaunė was a network. Decentralization is quite clearly visible here: intermediate distribution points were located in Čekiškė, Vilkija, Zapyškis, and Garliava. Books were hidden and later transported further on. Book smugglers are commemorated in the historical memory of many of these nearby towns, and graves have survived bearing inscriptions that those buried there were book smugglers or clandestine teachers.

The example of Garliava is particularly telling. The pharmacist Kazimieras Aglinskas, who lived there, stands out as a person who founded, supported, and distributed Aušra, Varpas, and other banned literature. His home became an important transit point, and more and more people were drawn into the activity. In Garliava, one can find not only a monument dedicated to him, but also a street named in his honor. Moreover, he was a close friend of J. Basanavičius.

In the second half of the 19th century, banned Lithuanian publications were actively distributed in Čekiškė even within the town’s multicultural environment. At first, prayer books and primers would appear in the markets, and later came the first newspapers, Aušra and Varpas, as well as other literature. Thus, book smuggling operated not only covertly in forests, but also in public economic spaces – places where people gather.

Another archetype also needs to be reconsidered: the punishments for this activity may not have been as extreme as we imagine through the lens of the Soviet occupation. “They didn’t – as in communist times – send people off for no reason to uranium mines to lose their lungs, but that doesn’t mean the penalties weren’t severe, and with repeated offenses, they could become very harsh indeed.”

Out of thin air

At least for me, one of the consequences of the war in Ukraine has been a reconciliation with the Catholic Church. In adolescence, it was cool to resist it, belittle it, and point out tax evasion and debauchery. But without Catholicism, without the stubbornness and resistance of this class, without the role of the Church during both Russian occupations, who knows how things would have turned out?

Book-smuggling networks were often woven with the help of the clergy. And the Church retained this role for nearly a century, up until late communism. It is no secret that immediately after the uprising, the tsarist authorities moved the Samogitian Priests’ Seminary to Kaunas, together with Bishop Motiejus Valančius himself. At that time, the clergy were the most educated segment of the Lithuanian nation, fully aware of the surrounding threats. It was priests who were the first organizers of the illegal publication of Lithuanian books. They were actively assisted by lay sisters and deeply devout women, as well as sacristans and organists.

Why is this significant? Because the Church had strong connections, structure, mechanisms, and capital. Priests often acted as intermediaries so that individual links in the book-smuggling logistics chain would not know one another and therefore could not betray each other.

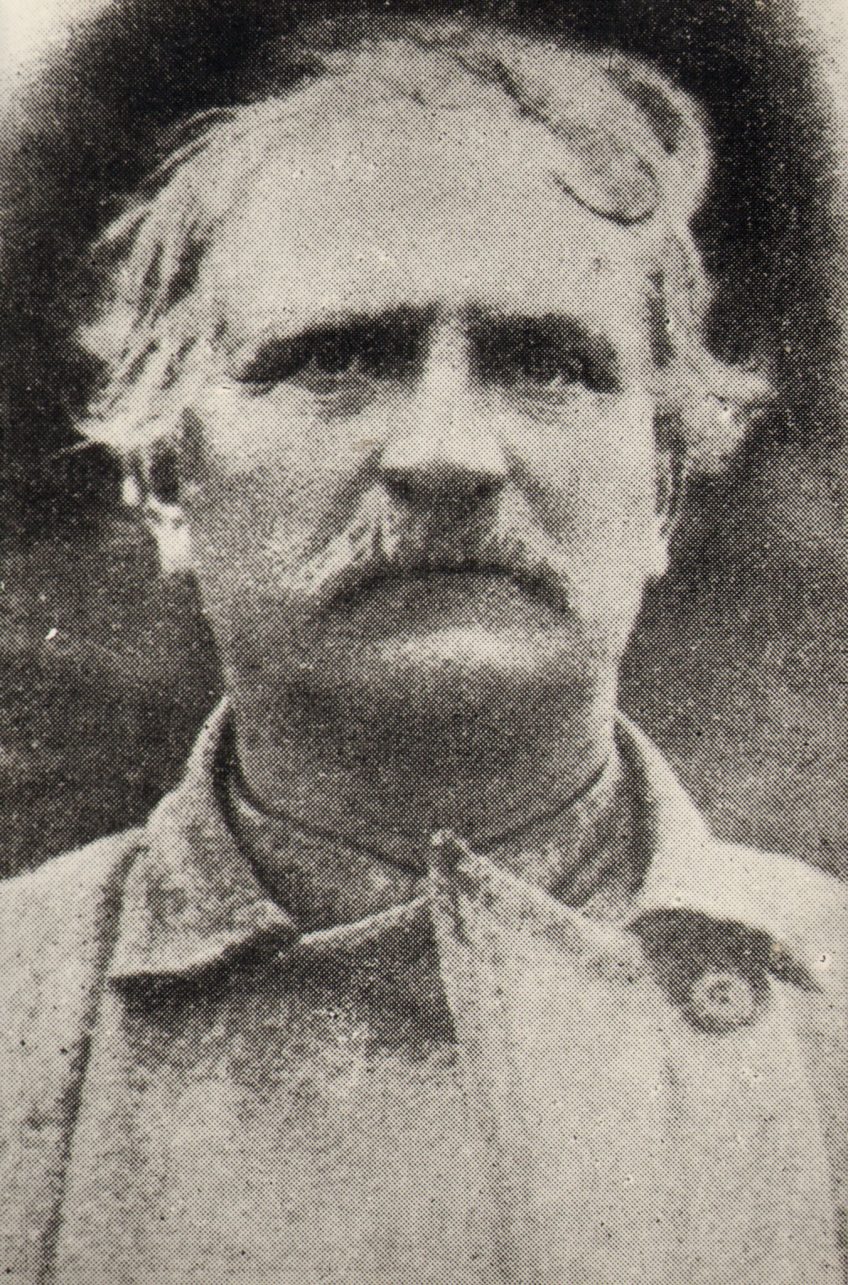

Book smuggler Jurgis Bielinis. Photograph – reproduction by an unknown photographer from an unknown

photograph, 2nd half of the 20th century. Lithuanian Museum of Education / LŠM III F 5597

And torturing a clergyman was, after all, somewhat more difficult and indecent even for the occupying authorities. However, the unbreakable stubbornness of Lithuanian priests was directly proportional to the severity of the punishments imposed on them. On the Book Smugglers’ Wall in the garden of the Vytautas the Great War Museum in Kaunas, 18 priests are commemorated among the hundred book smugglers. Of those who suffered most severely, six were the first martyrs of the tsarist regime’s repression: Antanas Brundza, Pranas Butkevičius, Kazys Eitutavičius, Motiejus Kaziliauskas, Vincas Norvaišas, and Pranas Straupas.

City’s memory

Book smuggling came to an end in 1904, when the ban on Lithuanian-language publications in Latin script was lifted, but it remained part of the nation’s and the city’s identity. During the interwar period, the garden of the War Museum became a place where the state shaped a language of remembrance: markers dedicated to book smugglers appeared, along with a sculpture and a wall bearing their names.

Along with books, the idea was carried that language itself was worth the risk. The freedom to think and to express one’s thoughts in the language taught by one’s parents was worth even exile. May these memories now be as vivid as possible in each of our minds, at a time when lies, arrogance, and political ambitions once again rise to higher positions than respect and concord.