Vytautas Jakelaitis, a Kaunas native from Aukštieji Šančiai who has “emigrated” to Vilnius, is a guide and motorcycle traveler, bringing the history of technology to life through actual travel experiences. By day, he works at the Energy and Technology Museum, and in the evenings and on weekends, he freelances as a guide through car museums, power plants, and the lesser-known parts of the city. When he is not planning routes for his personal guide and motorcycle traveler project, VyTours, he also plays the trombone in an amateur wind band. In motorcycling, he prefers moto-tourism over biker culture – a calm, curious pace where seeing matters more than reckless speed. This summer, Vytautas, following in the footsteps of the interwar period adventurers Matas Šalčius and Antanas Poška, went by motorcycle from Žaliakalnis to Athens.

Vytautas’ first path was that of music, and it involved a violin, birbynė (a type of Lithuanian reed pipe), and later choral conducting and lots of piano. There was also the army. “It seemed better to play in the army orchestra than to fight with the mujahideen in the mountains,” he recalls. Still, he was more drawn to technology, cars, and the computers of that time. “I started as a salesman, gradually climbed the ladder, and managed a medium-sized company.” Later came aviation, IT. And then?

“You know, according to new theories, we live longer than what is physiologically and psychologically allotted to us. That’s why changing professions prolongs your interest in what you do, and in life itself.” Eventually, Vytautas told himself, “Enough, I want retirement,” and that’s where the guide work came in.

“A salesman always knows how to tell a story,” Vytautas says. His father instilled in him a curiosity for technology, history, and science. That’s why his tours are not the classical ones: “Vilnius Bridges over the Neris,” the history of the railway, Pavilnys. “I don’t try to compete where everyone else is – in the Old Town. For me, the city is interesting as an organism of infrastructure.

But let’s get back to the bike.

The family didn’t have a car, but they did have a motorcycle. They would ride it to the garden in Gervėnupis, or to the forest for mushrooms. “I’m captured with that motorcycle more in photographs than in memory,” he smiles. Later, his father got into an accident, and his mother “banned” motorcycles for a long time. Only in 1988 did a red Jawa reappear in the yard and with it, Vytautas learned how to ride, sometimes unofficially taking it out. He got his driver’s license for a car, but not for a motorcycle, “Pure laziness. I needed to borrow a motorcycle for the exam, but I didn’t have enough friends in Vilnius, and I was too lazy to bring one from Kaunas, and that’s how it ended.” The two-wheeled engine disappeared from his life for a long time and only returned five years ago. “My wife wasn’t thrilled. Once she said: “Well, fine, insure yourself for five million and do what you want,” Vytautas laughs. But the desire won – a motorcycle appeared anyway.

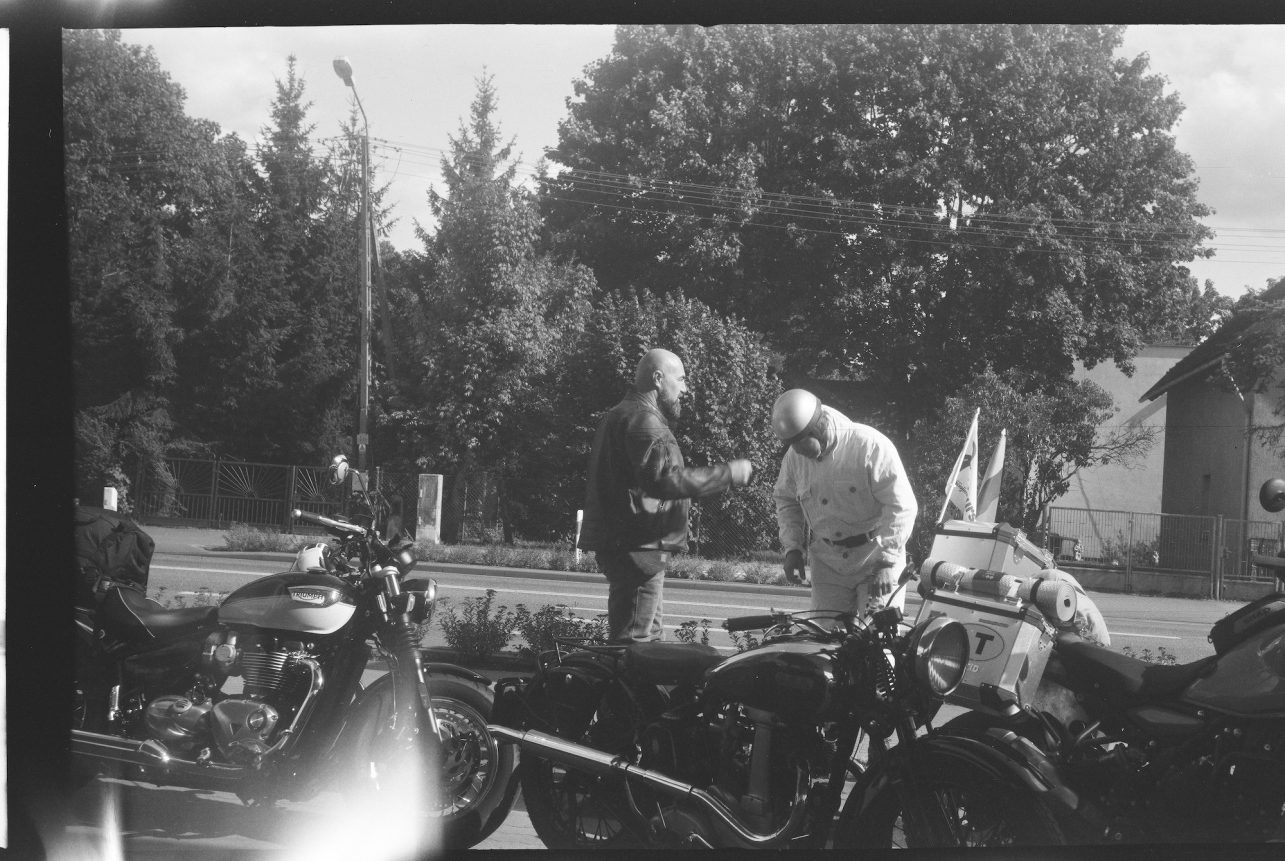

Today, his garage holds two motorcycles and a scooter. In the city, the latter is the most convenient. “For me, the motorcycle is a means to travel longer routes and see more.” As soon as he got his license, he hopped on a bike and rode away. He didn’t have his own yet, so his friend Raimondas Biguza lent him a first-generation Royal Enfield Himalayan. The journey was not grandiose, but true: the Baltic States, Poland, tents, overnight stays. Later, when he got his own motorcycle, he traveled to Vilnius suburbs, Lithuania, again to Poland, and other Baltic countries. A trailer for transporting the motorcycle appeared. “I prefer gravel and side roads. The trailer lets me avoid suffering – I can bring the bike to a place I find interesting and ride from there.”

Matas Šalčius entered Vytautas’ life unexpectedly. Through the self-service garage called Rūdys nemiega, a well-known journalist, Viktoras Jakovlevas, won the Prienai District Municipality’s Matas Šalčius Award. “I saw it and took Šalčius’ book off the shelf. As I read, I marked points on the map: which cities they traveled through, which bridges, which borders.” Rimas Bružas and Aurimas Mockus’ film From the Baltic to Bengal contributed to this, followed by libraries and archives. This gave rise to the idea of repeating their journey. “So I did. And then it seemed realistic to continue to Tehran, maybe even to India.”

Šalčius and Poška are two different but complementary characters.

Matas Šalčius was thirteen years older and, before that journey, had already traveled around the world. In 1914, he left for the Russian Empire, reached Vladivostok, moved to America, and in 1918–1919 returned to Lithuania. He was one of the founders of the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union, the second head of ELTA, and an initiator of the Tourist Association. After the 1926 coup, he quarreled with the nationalists – the journey became a new beginning for him.

Antanas Poška was born in 1903, and his key was Esperanto. During the First World War, a boy from Saločiai, at the age of eleven or twelve, was already translating for German units and helping to support his family. In his teenage years, he corresponded with Esperantists worldwide (even with the chief of police in Berlin), clashed with a priest over suspicious books (the priest tried to burn them), and moved to Kaunas, where he stayed at the Žiburėlis dormitory and worked in construction. In 1926, the Kaunas Radio Station was launched, and when canon Dambrauskas-Jakštas, who was supposed to host the Esperanto program, fell ill, Poška replaced him so well that the program remained his. The program was intended not only for Lithuania; the broadcasts reached Central Europe, and connections were established in Scandinavia. Esperanto functioned as a kind of social network with opportunities to find contacts, untangle bureaucratic knots, arrange lodging, and simply communicate at a time when English was not yet the lingua franca.

On November 20, 1929, Matas Šalčius and Antanas Poška departed from Kaunas. They traveled as far as Athens by motorcycle, then by ship to Egypt, and afterward by motorcycle again. Near Tehran, their FN motorcycle began to fall apart: problems had already started as they approached Greece. Antanas became seriously ill. Matas, who had already reached Tehran, returned, sold Poška’s motorcycle, and continued the journey alone. “I imagine Matas reasoned simply: why let a good thing go to waste?” says Vytautas. But both of them reached India: Šalčius sooner (around the summer of 1930), Poška later (around 1931). In India, Poška completed university, took part in ethnographic expeditions, and earned respect; he maintained ties with India until he died in 1992.

Why was the Enfield chosen today instead of the historical FN? Šalčius and Poška rode an FN M67B (500 cm³) – a motorcycle made by the Belgian arms giant. “They were bold in technology too – they were the first to build a four-cylinder motorcycle,” Vytautas explains. It was specifically the M67B that he searched for in museums and collections. At the time, in Poland, the known specimen was completely disassembled for a major overhaul; Germany and the Netherlands supposedly have one “living” example each. Vytautas chose the Royal Enfield Himalayan for two reasons: “First, Enfield produced motorcycles back then and still does today, so the historical parallel is fair. Second, Šalčius and Poška rode a new motorcycle; therefore, riding today’s machine is not a deception, but a logical continuation.”

Everyday life was difficult for them: fuel was scarce and of poor quality. As they approached Greece, they filled up with the wrong oil and damaged the pump: the engine overheated, forcing them to stop every half hour to remove the spark plug and pour oil into the cylinder through the spark plug hole. They managed to cover just 30 kilometers a day – and that was an achievement.

Vytautas deliberately coordinated his trip with the historical pace: 35 days to Athens, with stops in Prague and Sofia. The return trip took 2.5 days. “That’s the biggest difference: borders are almost invisible today, there is less bureaucracy, and the language barrier is disappearing.” The route has become different for the modern traveler: faster, simpler, but not inferior.

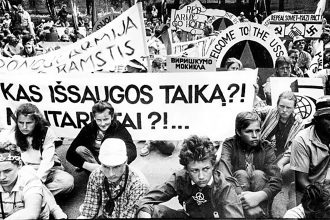

“I wanted to feel how the interwar period sounded in the air,” Vytautas says. “That’s why, in addition to maps, I also used the press for my research. Through it, the historical background opened up: from the death of Georges Clemenceau to the Polish government crisis; from the shadow of Trianon in Hungary to the legacy of the Ottoman Empire in Bulgaria and Greece. You experience not only where they traveled, but also what they traveled through. After all, we know little about the history of countries close to Lithuania, so this journey also filled in gaps in my own historical knowledge.”

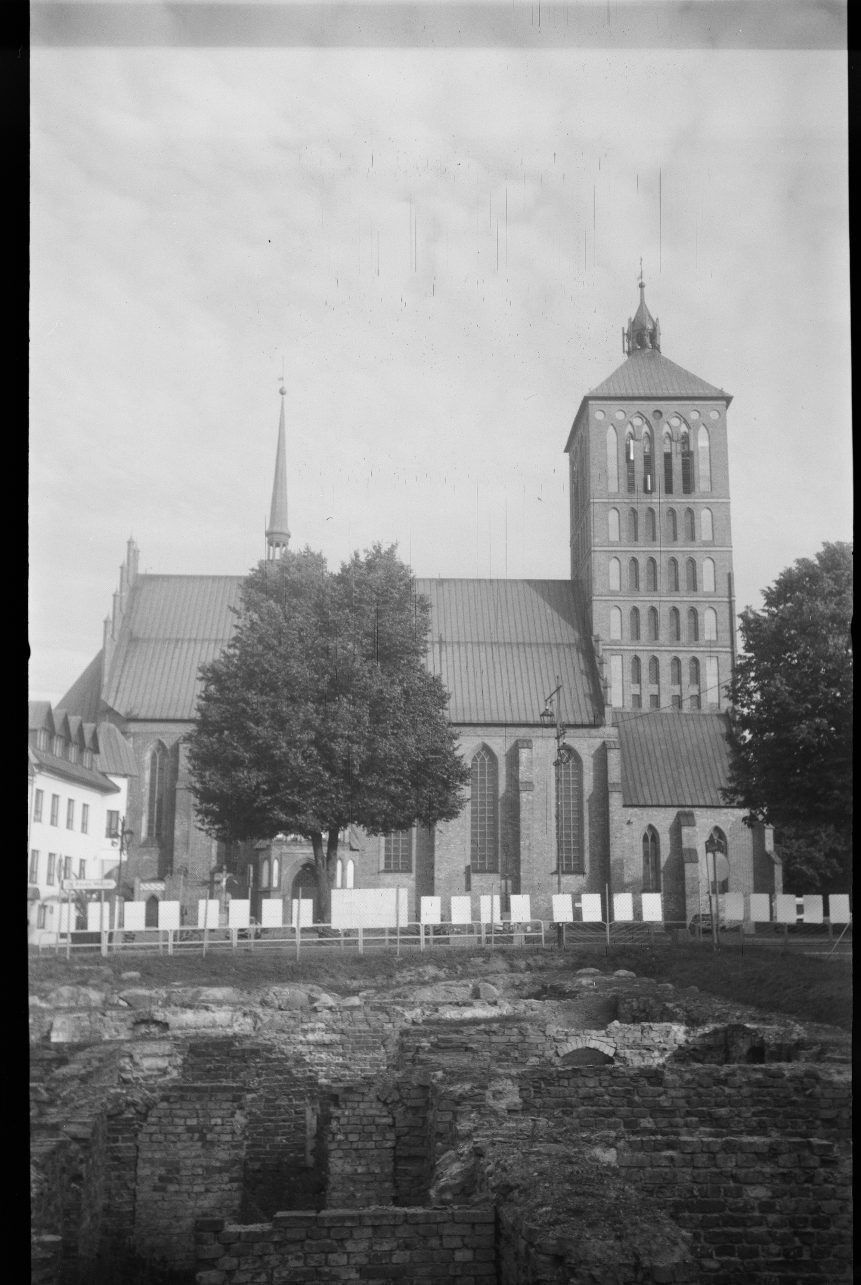

While traveling, he did not want to simply “buzz through” – he wanted artifacts. Hence, the decision was made to photograph on film, using a century-old Agfa camera. Photographer Romualdas Vikšra helped him find a working device, and a photographic materials company donated rolls of film. “I shot 20 rolls with 8 frames each featuring my journey and the places where the interwar period texture remains: bridges, roadsides, buildings. It’s a different rhythm: first you decide, then you press.” While searching for images from the historical journey, it became clear that only one photograph from Kaunas to Athens remained; Matas Šalčius’ archives mainly contain images from India and Indochina. The situation with Antanas Poška’s legacy is even sadder: part of his photo archive seems to have been lost (after being moved from the Esperanto Society’s premises to a Vilnius City Council warehouse and later, most likely, to the Kariotiškės landfill). “I still believe in miracles – that perhaps someone didn’t have the heart to throw everything away and those boxes are lying somewhere in an attic.”

Vytautas’ overnight stays were varied: mostly economy-class hotels, a few nights with motorcyclists in Poland (he found contacts by writing to the cities where Šalčius and Poška stayed overnight). In one case, through Bunk-a-Biker, he stayed with a local motorcyclist: a small apartment, a carpet on the floor, and the door left open, because both travel on two wheels. In Hungary, Esperanto came into play: a member of the community, a former bank director, showed him around the city and took him to the thermal baths. The planned public lectures for motorcyclists and Esperantists didn’t take place this time because it was the holiday season. But the embassies of Lithuania in Prague, Vienna, Budapest, and Athens opened their doors. “There weren’t crowds of people, but the reception was very warm. And most importantly, you don’t just talk about the route, but also about Lithuania today.”

The final destination of this journey was the port of Piraeus. “I want to continue from here,” says Vytautas. “Ideally, I’d bring the motorcycle over and take a boat to Egypt. And then the administrative realities would begin: Israel, Syria, Iraq, Iran – it’s no longer Europe. I’ll have to deviate from the historical trajectory and prepare more seriously. But it’s possible.”

What did the road teach him? First, preparation creates quality: archives, press, contacts. Second, improvisation brings discoveries: sleeping on a carpet, unexpected thermal baths, and embassies opening their doors. Third, anyone can travel today: fewer borders, shrinking bureaucracy, and technology breaking down language barriers. “You just need to get on the bike and go.”

When asked if he would consider Šalčius and Poška the first nomads (in biker slang, lone-wolf renegades), Vytautas shakes his head. “Apostles – that’s what I would call them. Bearers of knowledge. They went onto an unsafe, unknown road and spoke about Lithuania at a time when a small country still needed to learn how to be heard.”