“Anger would not have achieved anything. Our resistance relied on irony, humor, mockery, and unconventional actions,” says Saulius Pikšrys, founder and leader of the environmental organization Atgaja and the Lithuanian Green Movement. When asked whether seeing Lithuania’s nature and cultural heritage being destroyed during the Soviet era provoked anger, Saulius admits that such sights did indeed stir strong emotions, but they turned into creative energy that spread throughout the country. Rallies organized by Atgaja, one of the first environmental NGOs in Lithuania, would draw crowds of thousands.

(Text published in the September 2025 issue of “Kaunas Full of Culture” magazine, “Movements”)

My interviewee – Saulius Pikšrys – a representative of the last wave of hippies, became fascinated with nature, hiking, ecology, and culture back in his university years. During his studies, he led the hikers’ club Ąžuolas at the Kaunas University of Technology. It was in this organization that future members of Atgaja met.

“Every weekend, we traveled around Lithuania, and we referred to these hikes as “little rests.” It didn’t matter if it was winter or summer, rain or shine, we went out into nature, even during Christmas, to celebrate the Winter Solstice. Before the hikes, we would prepare literature and routes, visit hill forts, churches, and other cultural sites,” Saulius recalls. However, the hikers also saw the destruction of natural and cultural heritage: aggressive industrialization in villages and homesteads, widespread chemical use, fertilizer lumps scattered across meadows, collectivization, silicate brick farms built in Lithuania’s most beautiful corners, wastewater flowing into streams, and land reclamation projects that drained wetlands, destroying swamps and groves.

“I still remember a phrase I once read in a Soviet magazine, that a hilly landscape is unacceptable for a farmer and everything must be leveled flat,” Saulius laughs. These hikes and the destructive policies they revealed became a strong ideological foundation for the beginning of the Atgaja movement. However, the idea to establish the organization came later. First, a reliable group of people had to be assembled, and the future Atgaja members did this in their own way, by taking newcomers on difficult hikes.

“Through the swamp, waist-deep in mud, in the ploughed fields, where every boot gets covered in mud and adds fifteen kilograms of extra weight. Only the reliable and Spartan-minded endured, and the group bonded tightly. We have maintained ties with many of them to this day,” my interlocutor rejoices, and I calculate that these people have known each other for more than 45 years. Trudging through the fields turned out to be a recipe for lifelong friendship.

Saulius’ fellow hiker, a friend, and the future leader of the movement, Saulius Gricius, was also inseparable from the Atgaja movement. Although the first meeting during one of the Ąžuolas gatherings gave no promise of friendship. Gricius behaved impudently, made a lot of comments, and left the impression of an annoying guy on Saulius, who was the head of Atgaja at the time.

“Still, the next day we met at the faculty, had a smoke together, then went into the lecture hall, gathered our things, and after going to Saulius’ basement, we set about patching holes in a raft. That weekend, we went on our first trip together with the freshly repaired raft. From that day on, we became inseparable,” the man recalls of his friend. After graduating and starting work in factories, both Saulius and the other members of the hiking group didn’t abandon their passion. They hiked, sailed on rivers, and generated ideas during the Blue Nights sessions that had been started during their studies.

“On Wednesdays after the meetings, the hiking company would gather at one of the members’ houses. We would sit on the carpet, brew some very strong tea, and smoke. Drinking chifir and puffing on cigarettes, the air would get so blue and thick you could cut it with a knife. For these Blue Nights’ discussions, we’d come up with an ecological, cultural, or moral topic and philosophize until dawn. Sometimes we’d discuss a newly released vinyl record or a book. It was intellectual activity in a somewhat different form,” Saulius remembers of his youth.

Atgaja members were idealists aiming to change the world and organize grand actions, protests, and rallies. The right circumstances to officially establish the organization only arose in 1987. At that time, a decree was issued stating that organizations could be established “based on interests”. “And we thought, why not try it? We wrote to the Kauno tiesa newspaper that a founding meeting was being organized near Kaunas Castle, mentioning monument preservation and ecology as the main goals, after all, we had seen how heritage objects were being destroyed and vandalized.” The founders were Saulius Pikšrys, Saulius Gricius, Deivis Urbonas, and Džiugas Palukaitis.

Saulius remembers that as a rehearsal for later protest marches, back in 1985, he organized an experimental, several-day punk festival by the Bražuolė River. A few hundred people set up a cowboy-style camp, with concerts, games on the ground, in the air, and on the water; flags flew, and a sense of freedom prevailed. Later, Saulius Gricius and Saulius Pikšrys, together with active Atgaja members, made plans, organized actions, developed strategies, and formed initiative groups.

“Some things were complicated: logistics, dissemination of ideas, financing, taking care of inventory, and guests. Sometimes, a famous professor would come to the hike to give a lecture, dressed in a suit, wearing a national ribbon, and then we’d have to find him a tent, a sleeping bag…” Saulius recalls the surprises and nods his head in approval as I marvel at how all of this, especially the international actions, succeeded without Google, personal phones, or the internet.

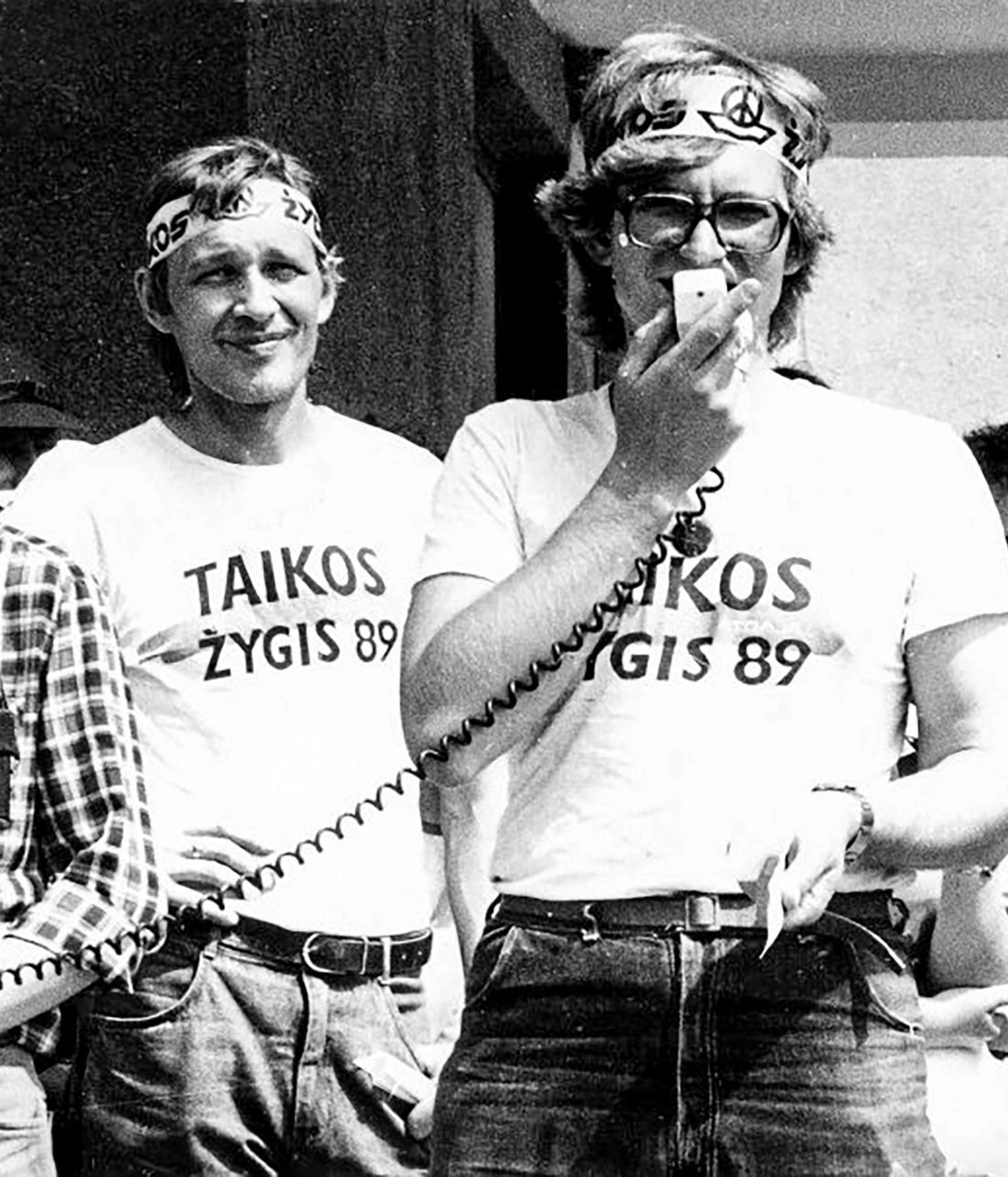

One such action was the Baltic Embrace organized in 1989, which Saulius remembers as a rehearsal for the Baltic Way. The action involved all the countries bordering the Baltic Sea. “Through letters, faxes, and telephones, we managed to organize people to go to the coast on a specific day at a specific hour. At that time, we got the idea to declare the first weekend of September as Baltic Sea Day, and we achieved that,” Saulius recounts.

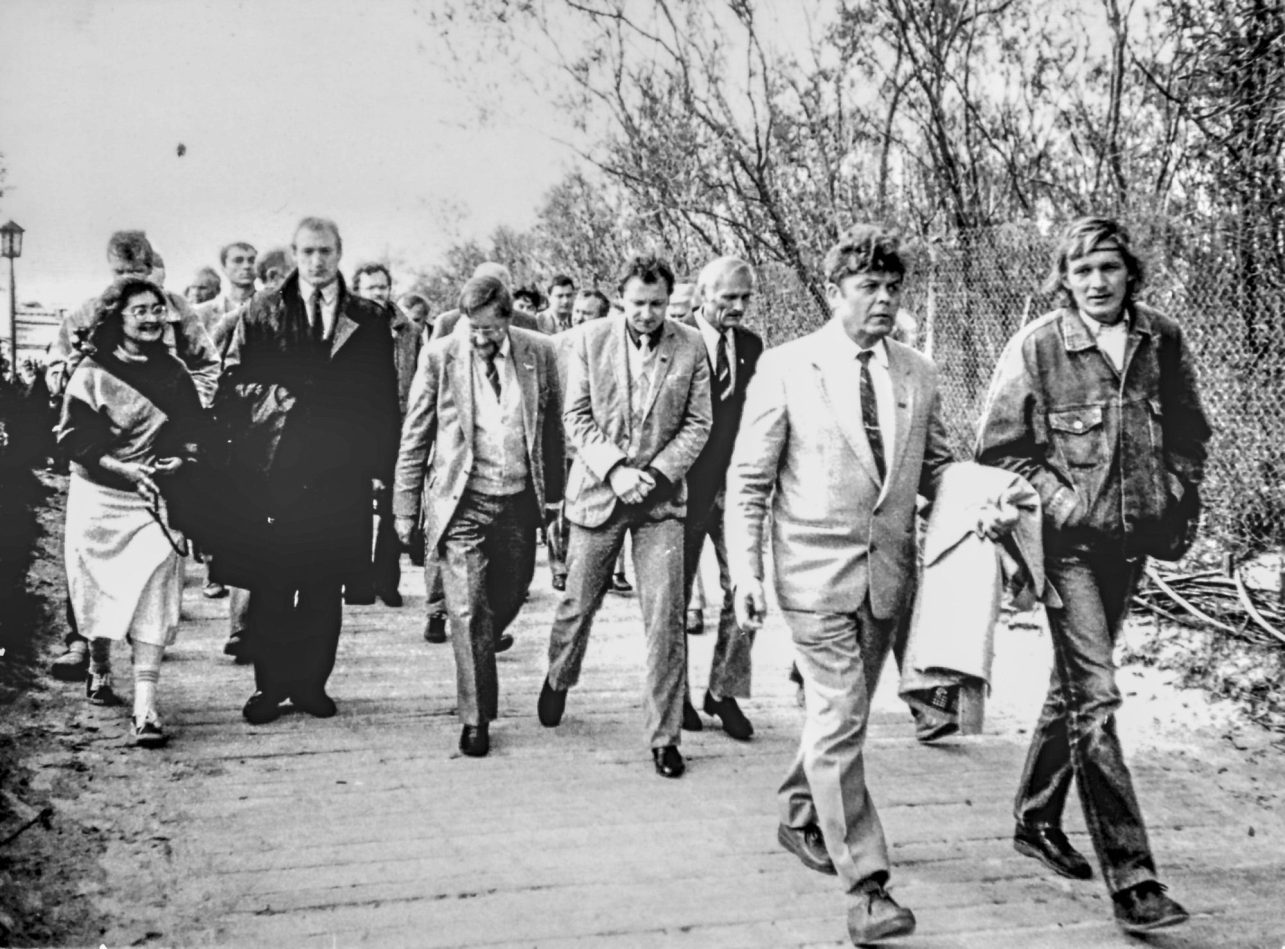

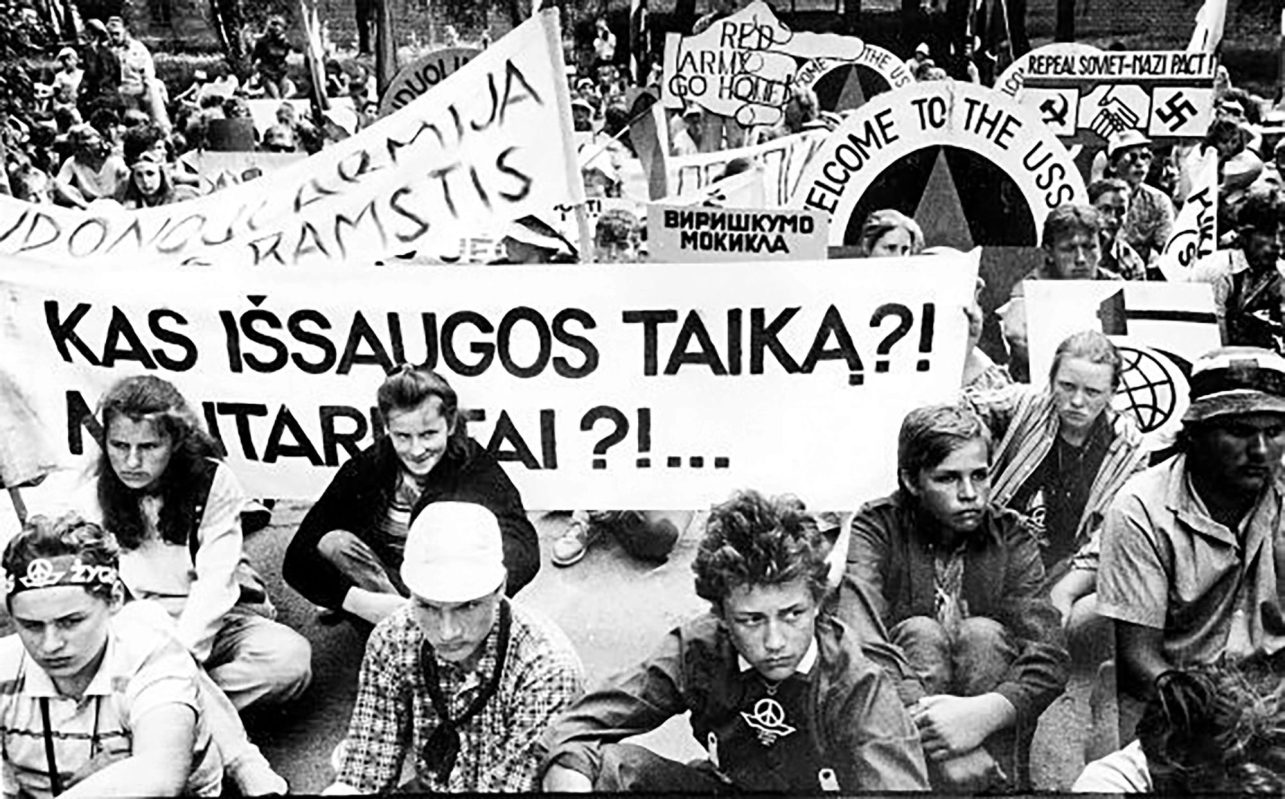

Atgaja was at the vanguard of the Reform Movement (Sąjūdis), using peaceful, bold, and eloquently silent forms of protest to awaken national consciousness. I listened to Saulius’ stories, admiring the youth’s ability to resist the Soviet system creatively by using powerful symbols. For example, in 1988, during an Ecological Protest March, Atgaja members carried the Lithuanian tricolor through the most remote corners of the country. Saulius recalls how impressive it was, especially in rural areas, where people wept upon seeing the hikers.

One of the most impressive events, both in terms of content and execution, was a peaceful silent action at a Soviet military base in Kėdainiai. At first, the activists planned to hold a protest at the unit gates, but after sending a scout, they learned that it was actually quite easy to enter the territory of the military airfield. Can you imagine – a crowd of about 800 people walked across the runway of the military airfield as if it were a podium, chanting slogans and waving flags, while soldiers watched from the side. “It was very brave. The soldiers had the right to give a warning, and if warnings were ignored, to open fire. Sirens were wailing in the background, but the soldiers just stood there, confused, not daring to act.” The participants of the protest had agreed not to give in to provocations and hold a silent protest near the airfield headquarters, holding posters that said, “Red army, go home.” The protesters spent an hour at the site, then, chanting slogans of shame, left the military facility through the wide-open gates held by the soldiers themselves.

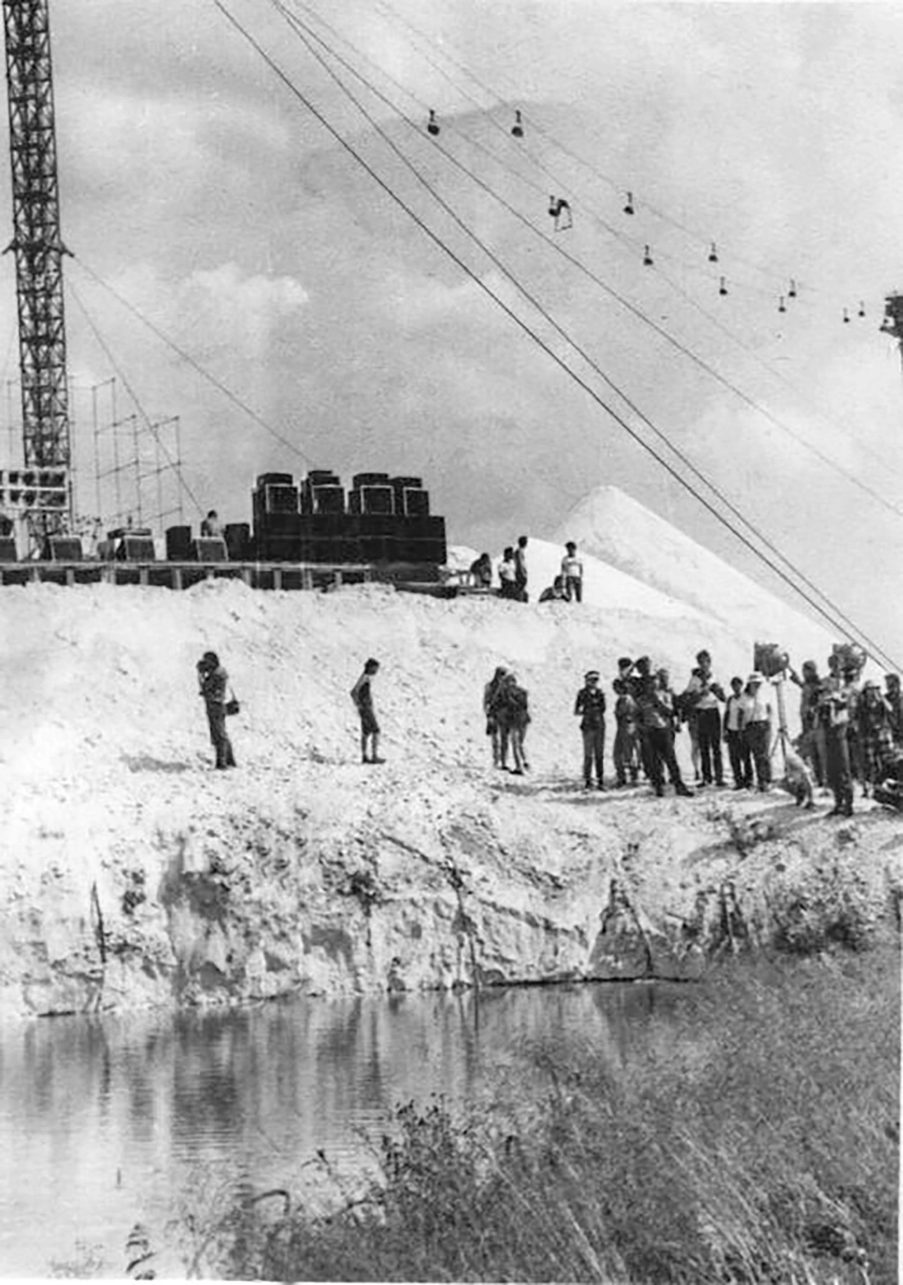

One of the most important protests for Saulius took place in Kėdainiai, on the mounds of phosphogypsum. At that time, the place looked quite different from what it looks like now. Above, there was a cable line along which wagons were moving and dumping production waste – phosphogypsum – across the territory. The landscape really resembled a field dotted with sharp-peaked mountains. Against this backdrop, during the Peace March, a concert was held, with at least six hard rock bands performing. Members of Atgaja took care of the stage, sound equipment, and even lighting.

Atgaja members also set up tent camps near facilities engaged in questionable activities. One such site, code-named Nieman, was located near the Kadagiai Valley. “We set up a camp there and stopped the construction, blocking the passages. Rumors spread that it was going to be a KGB radar station emitting dangerous electromagnetic waves. So we blocked the site until the purpose of the construction was clarified. Men in suits would arrive in black Volgas and take photos of us. “We spent at least a few weeks there,” Saulius recalls. At the same time, the Baltic Way was taking place, but since they couldn’t leave the site, the members tossed a coin. Saulius and a few comrades stayed to guard the facility. Still, the flowers falling from the sky that day reached them, too – the initiators of the Baltic Embrace also became participants in the Baltic Way. Atgaja members had also set up a similar tent camp near the Kruonis pumped-storage hydroelectric power station and even staged a several-day hunger strike next to the Kaunas municipality.

Saulius Pikšrys is a veteran of protests and rallies. Radical protests, questioning of institutions, and negotiations were the distinctive features of Atgaja in that era’s context. Nonviolent communication was important to the members, and they were all “ardent anti-militarists.” What does Saulius think about today’s protests? He says that this question has troubled him for many years. During Soviet times, the enemy and its moves were clear, so irony became a powerful weapon. Now Saulius misses resistance and wonders whether the revolutionary spirit has been overshadowed by conformism. Still, he adds that the Atgaja movement thrived only as long as there was a clear enemy, and as long as powerful ideas drove it. “When the economy collapsed in the early 1990s, ecological ideas became unpopular, because life was already difficult, and the Greens were calling for even less consumption. We couldn’t withstand this crisis,” Saulius admits. The death of one of the leaders, Saulius Gricius, in 1991 also became a turning point in the movement’s history. “Atgaja’s existence can be split into two parts: before and after Gricius,” says Saulius, and even decades later, comrades still gather at his grave. Most memories of Atgaja live on in the minds of contemporaries, and the movement was also immortalized in the 2015 film The Green Musketeers (directed by Jonas Öhman).

Hikes, festivals, discussions, and deep concern for the environment turned into the strong activist core of the organization. The members of Atgaja were radical but nonviolent antimilitarists who stood up to violence, pollution, and bureaucratic absurdity. The history of this movement shows how much can be changed through idealism and, above all, togetherness. It was togetherness that protected Atgaja’s leaders from an attack at a Soviet military site, which inspired them to organize festivals and play rock music on phosphogypsum hills. If one person can generate a wisp of smoke, then a group of people can create the entire thickness of blue nights, to which the ideas of freedom and resistance have so strongly attached themselves.