I had long wanted to interview the long-time architect of the Urban Construction Design Institute from the Kaunas branch, who later served as the head of the Strategic Planning Department of the Kaunas City Municipality, and there could hardly be a better occasion than the anniversary of Šilainiai. After all, it was precisely in the hands of Saulius Lukošius and his colleagues that this northern corner of Kaunas took on its present appearance – the one seen by everyone who has at least once traveled along the country’s main highway, the A1.

(Text published in the August 2025 issue of “Kaunas Full of Culture” magazine, “Šilainiai”)

The road toward urbanism

We will not learn much about S. Lukošius’ personal life. As he himself says, he is a modest man who does not like attention. Still, he claims to be steeped in the spirit of the interwar period. His parents were teachers, apolitical. Yet what had a particularly strong influence were the childhood summers spent at his aunt’s, where he read quite a few magazines from independent Lithuania. Saulius does not hide the fact that the national romanticism, which no longer exists today, left a deep impression on him and continues to shape his thinking to this day.

The interviewee completed his architecture studies in 1971 in Kaunas, at what was then the Polytechnic Institute. We meet not far from his alma mater, just across the street from what is now the KTU student campus, in the well-known architects’ colony on Plieno Street. More precisely, in the country’s very first semi-detached houses.

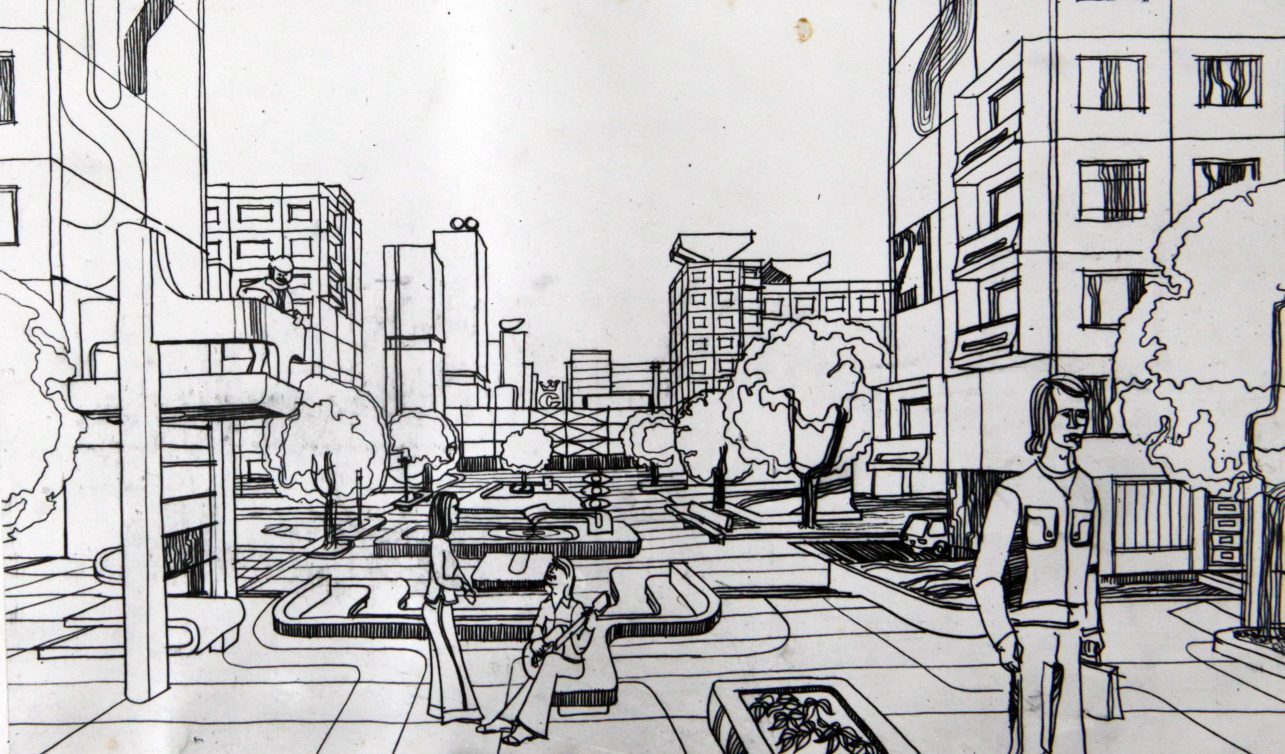

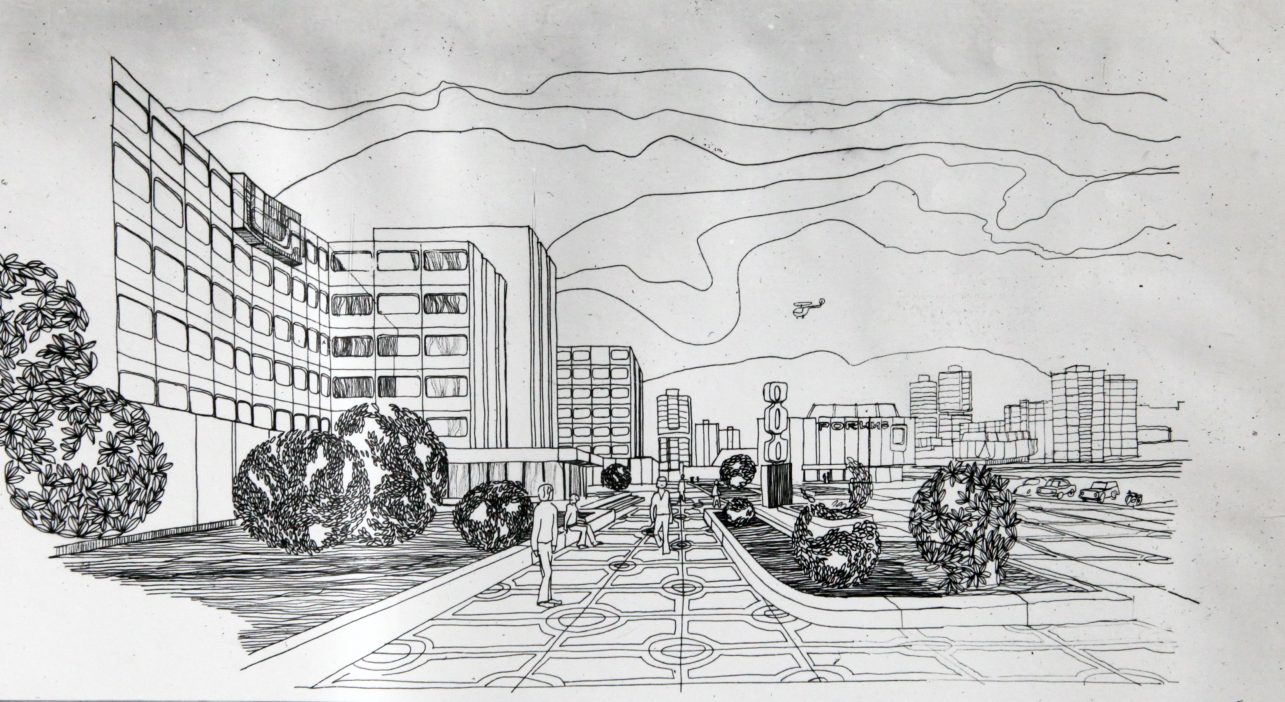

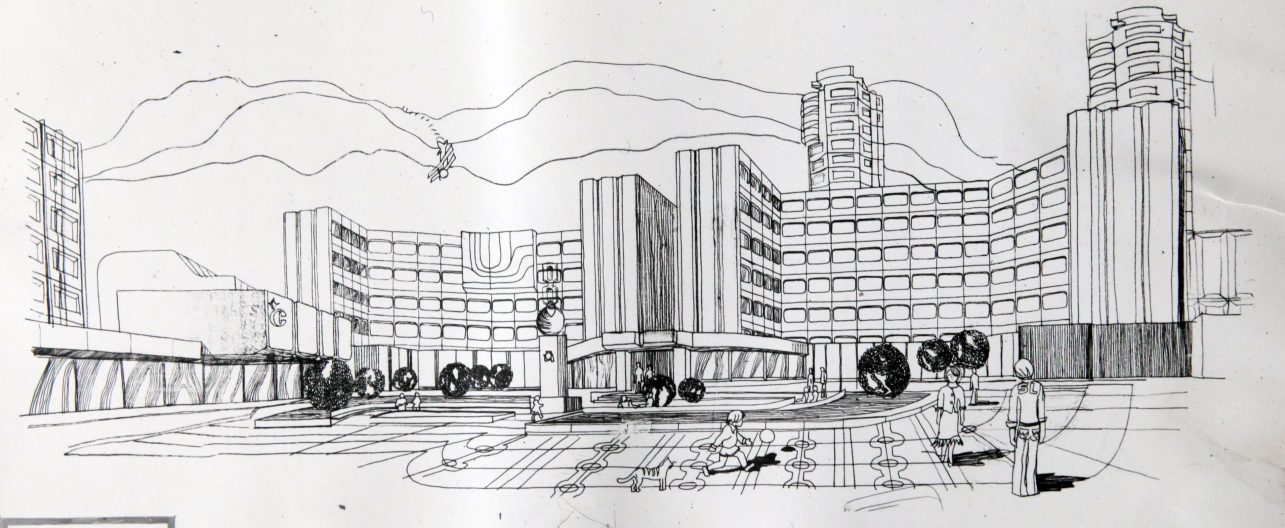

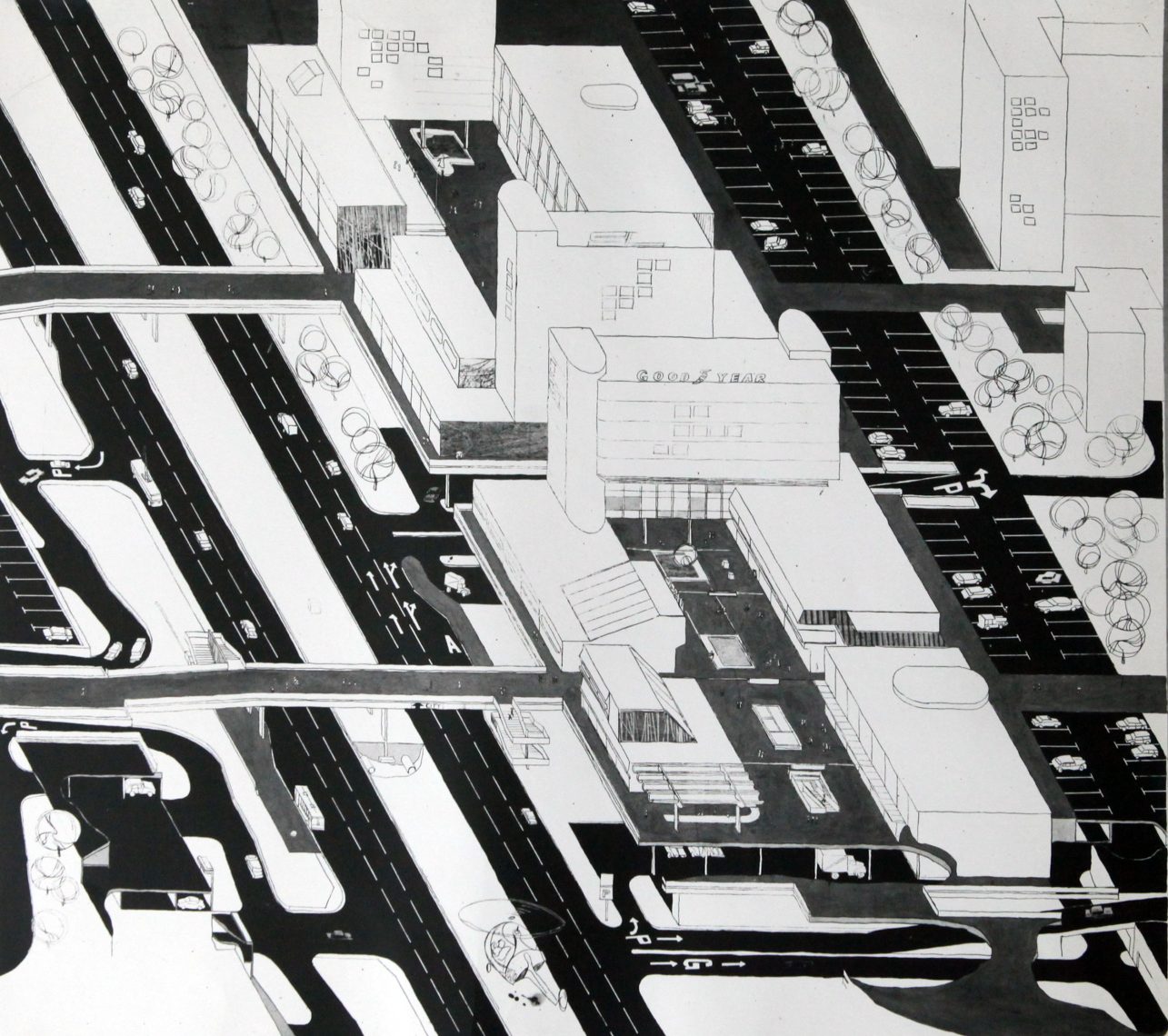

Incidentally, Saulius also graduated from a night drawing school. This is evident when looking through his sketches, urban perspectives, and silhouettes of Šilainiai. They are precise and detailed, yet do not lack creativity. In today’s era of often misleading 3D visualizations, they are a breath of fresh air for the eyes. Another curious fact: the interviewee once played in the rock and roll band Kertukai.

“I realized that I was more drawn to urban planning. At that time, I did not look up to my architecture professors. There was a lack of strong personalities, and there were enough number crunchers at the institute. We had an extraordinary thirst for knowledge, but the system was such that it didn’t allow it. Over time, I saw that urban planning is a completely separate field: architecture is the realization that comes after urban design. I did not want to be a multiathlon athlete; I wanted to focus on one thing,” we begin the conversation in S. Lukošius’ office.

At that time, the KPI (Kaunas Polytechnic Institute) had two clear directions: architects who were called volumetric designers, and planners. Architects, whether you like it or not, are more artistic. As Saulius says, he is not like that. He is a rationalist, a thinker. He was always more drawn to optimizing the life of the working person, improving quality of life, seeking solutions to the city’s meta-questions, and navigating between what is possible, feasible, and necessary.

“Urban planning is invisible. We do not feel it, just as we do not feel the weather. But just as we notice when the weather worsens, we get the sense that something isn’t right when we sense a poor urban fabric. We see architecture, but urbanism is ourselves. With the sum of our own and others’ lives, and its infrastructural expression,” explains the longtime Kaunas city planner, pulling the Šilainiai Album out of the shelf.

The jazz of names

The current territory of Šilainiai was essentially empty and very suitable for mass construction. It encompassed the villages of Milikoniai and Smėliai, as well as the remnants of the manors of Linkuva, Vytenai, and Sargėnai; it was built south of Kaunas’ northern bend, the current Islandijos Highway, and east of Žemaičių Highway. This is the last Soviet-era residential district of Kaunas, preparation for which began in 1981, with residents arriving in 1985. Today, it is the largest eldership (administrative division) of Kaunas city, containing one-fifth of all the city’s streets.

Another village that was not mentioned is Šilainė, which was near Romainiai. It was not located in the current Šilainiai territory, but beyond the Veršva Valley, toward the Romainiai cemetery. It still remains there: roughly between the ditch and the western bypass. This small settlement of about 20–30 houses became the inspiration for the entire new, largest district of Kaunas, whose construction lasted all the way until 1994.

According to the interviewee, it was the then-chief city architect Algimantas Sprindys who was “to blame” for the entire new district not being named after the closest or largest former settlements, such as Smėliai or Milikoniai. The architect didn’t like those names, so the name of a more distant village was chosen instead. The reference to šilas (pine forest) also suited the chosen theme of the street names.

I call these settlements villages because they were just a few small houses, which, by the way, received respect – the old homesteads with plots were not demolished, but integrated into the microdistrict. That’s why even today in Šilainiai you can find old wooden houses that recall past eras. The most prominent example is Mosėdžio Street, which, according to the interviewee, has not been touched at all and has not been swept away, as was customary “under the Russians.”

And how did the street names come about? “Since Šilainiai was “towards the sea,” it was decided to give maritime-themed names. That’s how Vėtrungės, Šarkuvos streets, Baltų Avenue, and so on came about. The executive committee took a relaxed approach to this. With the same sea idea, small pine groves appeared on the slopes – we wanted to bring the Baltic Sea closer to the newest Kaunas development.”

There was no team

When I asked Saulius about the origins of the vision and who was on the team, I got a rather firm answer: “There was no team. Such a word didn’t exist in the vocabulary back then. The idea of a competition came up in the city’s executive department. Juozas Putna, a big supporter of competitions, was behind it. After two successful competitions, Taikos and Eigulių, I decided to enter the Smėliai competition, and I won.”

Mass residential construction in Kaunas was always delayed. City planners, urbanists, and architects worked faster than the builders: plans were made quicker than the city could lay the necessary infrastructure. In many cases, the networks appeared at the last moment or only after residents had already moved in. Therefore, quite a lot of time passed between the announcement of the tender and the start of construction.

Saulius won the competition in 1976, but the first apartment building only began to rise in 1984. The development of construction areas in Kaunas stalled. Due to delays in communications infrastructure, even new parts of the city appeared, for example, the so-called Saulėtekis district emerged because networks were not extended to other parts of the city, but there was a demand for apartments. The same happened with the 4th microdistrict of Eiguliai. There was supposed to be a city stadium with 50,000 seats, but delays in Šilainiai networks meant apartment buildings were constructed instead.

Many of the Soviet-era districts were designed to serve industrial or manufacturing zones. For example, Dainava served the factories along what is now Pramonės Avenue and Elektrėnų Avenue, while Vilijampolė served the factories along what is now Raudondvario Avenue. But did Šilainiai also have to serve something, to satisfy the late Soviet industrial ambitions and provide a convenient proletarian life set away from the city center? Why was this particular location chosen for them? Why didn’t it expand southward?

“Kaunas was designed like Moscow, following the onion principle. The author of this post-war idea was Petras Janulis, the founder of a famous dynasty of architects. In my opinion, this is not a very good plan because it has many inconvenient, ill-considered areas and feels like an unnatural, Moscow-style centrism. So after developing the east, south, and west parts of Kaunas, it was time for the north. No industrial enterprises were planned here; this was already the late Soviet era, which was different.”

In 1984, at the construction site of the first apartment building, a capsule was buried. “The first, of course, in the 1st Šilainiai microdistrict. A five-story building. Either at Jotvingių St. 1 or Jotvingių St. 3, next to the street. It separates the yard from car noise and the main traffic towards the city bypass.”

Not everything went as planned

If we looked at the plan, for example, of the layout of the 3rd Šilainiai block, we would see that here and in many other places, reality differs from the plan: the once dynamic arrangement of buildings was simplified, and the scheme was more primitive. The truth is that many original, smart, and necessary urban ideas were not implemented. There was a constant intertwining of interests between those who came up with ideas and those who held the power to realize them.

“You see, the house-building company gave the orders. Their representative would come to Miestprojektas, shake his finger, and order changes. Construction at that time was based on quotas – thousands of square meters per year. If you start experimenting, you lose your metrics. Political stuff,” S. Lukošius continued.

“We planned all the main streets to be recessed to hold back noise, pollution, and separate traffic from people’s lives. We planned to build underground parking lots along the streets. None of it got implemented, even though I calculated the soil balance. The builders were powerful; they rushed to the committee and declared that we had come up with nonsense. That’s how one of the key details disappeared: the street screening, which was praised and even copied by Estonian urban planners,” the designer recalls.

The goal was to create residential spaces from which automobile traffic was completely eliminated. Cars were only supposed to enter but not be visible in the daylight within the neighborhood. Bridges and promenades leading to public spaces – shopping centers, clinics, and so on – were planned above the streets. Today, this has become one of Šilainiai problems: highways are located close to homes, there is a lack of parks, green spaces have been destroyed, and noise pollution is a serious issue.

Šilainiai Park was also left unimplemented, or rather, its largest part. “It was supposed to be three times larger than what remains today. At that time, the construction combine had absolutely no interest in building green spaces because they did not meet the quotas. So instead of spaces needed for humanity, we now have dense development that does not reflect the original vision of the neighborhood. It’s sad that densification continues, and there is no room left for green zones.”

Present and future

Šilainiai is a controversial district. Some compare it to the film The Irony of Fate, which (thank God) is no longer shown on our TV during New Year’s celebrations. For others, it is the most convenient district in Kaunas, with a broad service sector, easy transportation, and uncongested streets. For passersby, it resembles the crown of Kaunas, marked by the famous elevator shafts above the apartment blocks and panoramic views of old Kaunas.

Yet for some, it is a source of inspiration. Šilainiai is getting more modern every day, and community spirit is promoted by various cultural and social initiatives, discussed in previous and in this issue of the magazine. According to many, it is the best neighborhood to raise children. There’s a school nearby, shopping centers, opportunities to escape the city, a clinic, a hospital, and kindergartens.

In the coming decades, Šilainiai is expected to undergo significant renewal – new green spaces, bike paths, and modern buildings are planned. The harmonious expansion of apartment renovation programs could make Šilainiai one of the most progressive districts in Kaunas, combining convenience, ecology, and quality of life. And the gray shades of Šilainiai are already in dire need of change, especially in repairing damaged plans that were supposed to ensure harmony between man and car.