After our conversation, artist Roberta Daugėlaitė noted that we had created a rondo. The phrase “Don’t run away from yourself, you won’t find anything better” became the leitmotif, or more precisely, a chorus of the interview, which rhythmically alternated with the performer’s story about her activities, hobbies, studies, and life discoveries. In music, this would resemble the familiar rondo structure: a-b, a-c, a-d.

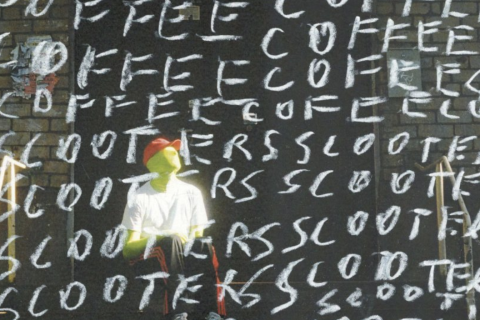

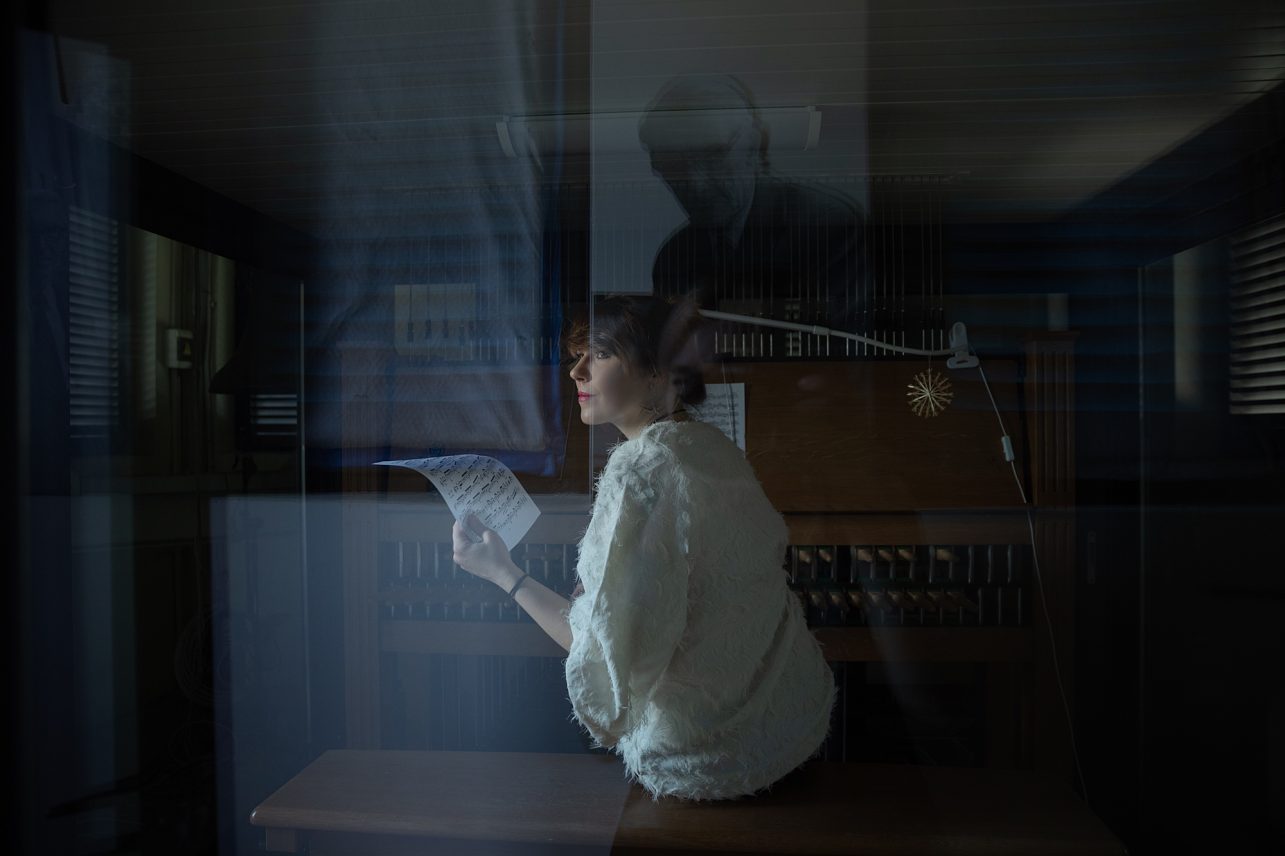

There was no doubt that Roberta’s life is rooted in music. She even mentioned how she constantly analyzes sounds during rehearsals, concerts, on the street, and in nature, sometimes consciously escaping into the quiet realm of drawing. However, you can also find Roberta admiring architecture, taking photographs, singing in churches, or hear her in Vytautas the Great War Museum carillon concerts and rehearsals ringing out throughout the city.

As you’ve probably gathered, this time we’re not talking about the usual kind of slowness, but about the unhurriedness that is created between rapidly changing sounds, thoughts and experiences, allowing you to hear yourself, even if it is only for ten minutes.

Roberta, I still remember the title of your 2019 exhibition at the Balta Gallery: Don’t Run from Yourself, You Won’t Find Anything Better. I’m curious – where do you (re)discover yourself these days? What are you like at this stage of your life?

These days, I feel like I’m close to myself. I’m not fully me yet – not fully Roberta – and there still isn’t enough time in a day to devote to all the areas that interest me. I’m deeply influenced by emotion, by feeling, and when those are especially intense, time fades into the background – I lose all sense of boundaries between activities. I’ve come to terms with that, but I do have to make an effort to take care of my health, and most importantly, not forget my loved ones, relatives, friends and colleagues, with whom sometimes a cup of coffee is half a year late.

You have a wide range of activities: accompaniment for students, choirs, performers, participation in instrumental, vocal and experimental music projects, drawing, animation, photography. How did you develop your endless curiosity about the world?

I’ve always had a deep desire to explore the world – it’s part of my nature. While studying at Kaunas Juozas Naujalis Music Gymnasium, in the piano class of the deeply music-loving teacher Birutė Kumpikienė, twelve years of pursuing that single path and aiming for a solo pianist career wasn’t enough for me. I felt a strong inspiration to also study collaborative piano (I’m grateful to my late teacher Aveniras Ūsas for that). In school, my musical world expanded through choral singing, which I had the chance to explore alongside my father, choir conductor Rolandas Daugėla. That drew me even closer to ensemble and chamber music.

And fine arts was a quiet form of therapy – it emerged as a path alongside music, where I could find rest. I delved into existential philosophy, philosophical anthropology, the mysteries of religion and spirituality, architecture; I was interested in zoology, especially the secrets of reptiles and arthropods, as a way to overcome uncertainties and phobias. I explored the art of sewing (both of my grandmothers were seamstresses). The funniest part is that even in my grandfather’s garage I found fascinating observations of metalworking and carpentry, imagining that one day I’d become a master of the most beautiful birdhouses. Now I’m wondering what kind of sound can be drawn from glass. Could a window have its own musical note – and an entire composition written just for it? These past few years have given me courage: I’ve dared to realize long-held dreams and stepped more boldly into alternative, experimental music – a space I had to grow into.

Through all these things, I try to understand the essence of the world, and my desire for knowledge just keeps growing. But I often find myself lost – I want everything, and I don’t know how to grasp it all within one lifetime. I burn out and eventually retreat into my own shell for a while. But my surname, Daugėla, means “to give a lot” or “to take a lot.” So the phrase “don’t run from yourself, because you won’t find anything better” is always close to me.

You became interested in Gregorian chant, became a collaborative pianist, and are a member of several ensembles. How did you start your professional career?

It’s my family’s contribution and influence – both my parents are musicians. I studied collaborative piano at the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre under Professor Irena Armonienė, and chamber music with Professor Petras Kunca. I found the experience of being a collaborative pianist – performing ensemble music together with another performer, engaging in a dialogue on the stage – very fulfilling. It’s especially rewarding to perform chamber music with my flutist brother, Romantas. During my master’s studies, I spent half a year at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, where I internalized the most important psychological insight for a musician: you don’t need to be afraid of making mistakes. That’s something I would also wish for those who teach young musicians. A mistake can serve as encouragement to feel freer on stage – when you slip up, you should confidently recover and turn the mistake into music, without taking on a sense of guilt. After finishing my master’s degree, I returned to Kaunas. After a long period of reflection on what to do next, I enrolled in photography studies at a vocational school and later joined preparatory jazz vocal studies at Vytautas Magnus University. This improved my technique and broadened my musical thinking.

Was it difficult to return to Kaunas?

I moved back with the thought that I would soon return to Vilnius – that city is in my heart, inspiring me with its active cultural life, spaces, and old town atmosphere. But then my love for Kaunas modernism exploded, the city opened up from a different angle and everything turned upside down. I can say again: don’t run from yourself, you won’t find anything better [laughs]. I’m a third-generation Kaunas native and a patriot of my city. When I came back to Kaunas, I was also invited to work as a piano accompanist with VMU classical vocal students before the final spring session, and I had to learn 54 pieces in a week. At peak times it is difficult for a pianist to relieve stress from their shoulders and hands, and unfortunately, I strained my hands and basically irreversibly damaged my working tool. Later, jazz studies showed me techniques and ways to ease tension in my hands, which allowed me to play again. Ironically, this opened the way to new methods of technical performance and score analysis, delving more into other styles so that I could be where I am now.

You talk about the physical and psychological strain of being a performer. What is it that keeps you on this path?

I couldn’t live without touching the piano keys or singing. Listening to music is a real art. At first, we hear noise, later we hear a line and after some time we understand the beauty of the style and eventually the harmony line stirs so many emotions that it becomes hard to breathe. Still, you often have to separate work from leisure, because a musician’s ears are always working and analyzing music. There was a time when I couldn’t relax at any concert; my mind was always working and analyzing, but eventually I learned to switch off critical thinking and just enjoy the concert.

You sing and play the organ during baptisms, wedding ceremonies or funerals. What do these experiences give you?

My connection to this experience comes from childhood. From a young age, I observed my mother and father singing at wedding ceremonies alongside the late priest Ričardas Mikutavičius at the Vytautas the Great Church in Kaunas. Singing during special life events is truly one of the most sensitive touches; you gift people a deeper meaning. Symbolically, I feel closer to the darker, sadder world because there is more true beauty there: the one note in minor that unfolds into major represents the subtle beauty and light of an entire life.

The Church is not the only place that brings your activities closer to the sky. On the first weekend of September, you will also play in the Kaunas Carillon Festival presented by Kaunas Artists’ House.

The festival has already become a tradition featuring the finest performers from carillon music world. I also encourage you to visit the garden of the War Museum on Sundays at 4 p.m., where the bells will ring until October. And the program alongside me will be performed by carillonist Austėja Staniunaitytė-Proietta, who will perform a four-hand duet with Raimondas Eimontas.

Invited by actress Edita Niciūtė to collaborate, I composed music for the poems of the Šilainiai community poets, and we released the album called Virsmas. One of the poems was written by Kaunas carillon player Raimundas Eimontas. I asked for carillon lessons, and seeing potential and promise, the carillon player entrusted me with his beloved instrument. It was a very thoughtful gift on his part, and it opened up a new instrument for me. We have a magnificent Royal Eijsbouts carillon with 49 bells in Kaunas. The technical possibilities make it quite difficult to compose and arrange, but all genres and repertoires can be adapted. Though one must remember that a carillon rehearsal becomes a concert for the whole city.

What practices or rituals help you pause?

This is how Gregorian chant came into my life. Every August, Kražiai hosted a week of Gregorian chanting and philosophy studies called Ad Fontes. Participants lived according to a monastic routine. When over a hundred people sang a single line, I experienced an inner breakthrough, cleansing from the meaningless running, stress, and expectations. These are mysteries of faith, embodied in spiritual and musical unity, encouraging gratitude for everything we have. The Ad Fontes week culminated in the opportunity to participate in concerts across Europe with the international women’s vocal ensemble Graces and Voices. Now, my escapes take place in nature: a lake, silence, a boat, watching grass grow, or a mosquito circling around. For a sensitive soul, being alone is essential.

How do you maintain curiosity and sensitivity to your surroundings?

Taking a step back helps – even if it’s just for 10 minutes – to see and understand from a distance which colors or shades are missing in that idealist’s painting. Life is so simple and beautiful; you just have to learn to let go of the complex chaos of your thoughts. You don’t have to go to the other side of the world; sometimes, all the inspiration in the world is right under the tip of your nose. I have a lot of people I love by my side, and that gives me the greatest happiness and inspiration. I cherish the values I was brought up with. I believe that it is family that inspires me not to lose authenticity, freedom, integrity, respect, and meaning.