We’re used to thinking that everything around us changes very quickly. But let’s take a step back and check if Kaunas really changed that much over the centuries. If stepping back across the street isn’t enough, let’s step back a few more streets or take a look from above. Inspired by the exhibition Laisvės alėja XIX a. vid. –XX a. KRVA dokumentuose (Laisvės Avenue from the Mid-19th to the 20th Century in KRVA Documents) at the Kaunas Regional State Archives, we attempt to take a look at Kaunas from a more distant, elevated, and most importantly, slower perspective.

You can visit the spaciously modest but profound exhibition in the small hall of the Kaunas Regional State Archives by prior arrangement. “All maps and plans are authentic. Every one of them is preserved in our archive,” emphasizes our interviewee, Nijolė Ambraškienė, one of the exhibition’s curators and a senior specialist at the Kaunas Regional State Archives, where she has worked for three decades.

Can we trust it?

The surviving and known maps of Kaunas date back to the mid-18th century. According to the curator, the oldest known plan of Kaunas was drawn in 1774 by H. D. Schultzs, titled in Polish simply as “Plan miasta Kaun.” However, an even older and well-known engraving by cartographer T. Makowski was created in the early 17th century.

“We should approach it – as well as other plans and maps – with caution. Don’t trust without verification,” says Nijolė Ambraškienė. “Makowski clearly exaggerated the number of houses. It may look impressive to us – a big city – but in reality, it was much more modest. The development was not nearly as dense as the engraving might suggest.”

Discrepancies also appear in later documents: some show plans that turned out to be different in reality. Some goals were not achieved, and others were smaller in scale than expected. For example, was there truly a Sun Square on my native Rytų Street, or was it just a widened part of the street?

Change was slow

Despite being the second-largest city in Lithuania, Kaunas is not very big. Looking at its historical and architectural layers, we see that major development began less than 200 years ago, with more active growth starting about 100 years ago. Therefore, Kaunas was an ordinary small town until the mid-19th century.

“We can talk about the beginnings of Kaunas as a city around the year 1408, when it was granted Magdeburg rights,” the conversation continues. Before that, Kaunas was more of a settlement clustered around the castle, showing only the early signs of becoming a city, such as having a wooden church.

Clearly, the part of Kaunas that changes the slowest is the Old Town. Nestled between two rivers, it was naturally separated from Aleksotas (annexed in 1932) and Vilijampolė (annexed in 1919). The Kaunas Town Hall, the Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul, and Kaunas Castle, all located here, are among the oldest reference points when viewing the city from above.

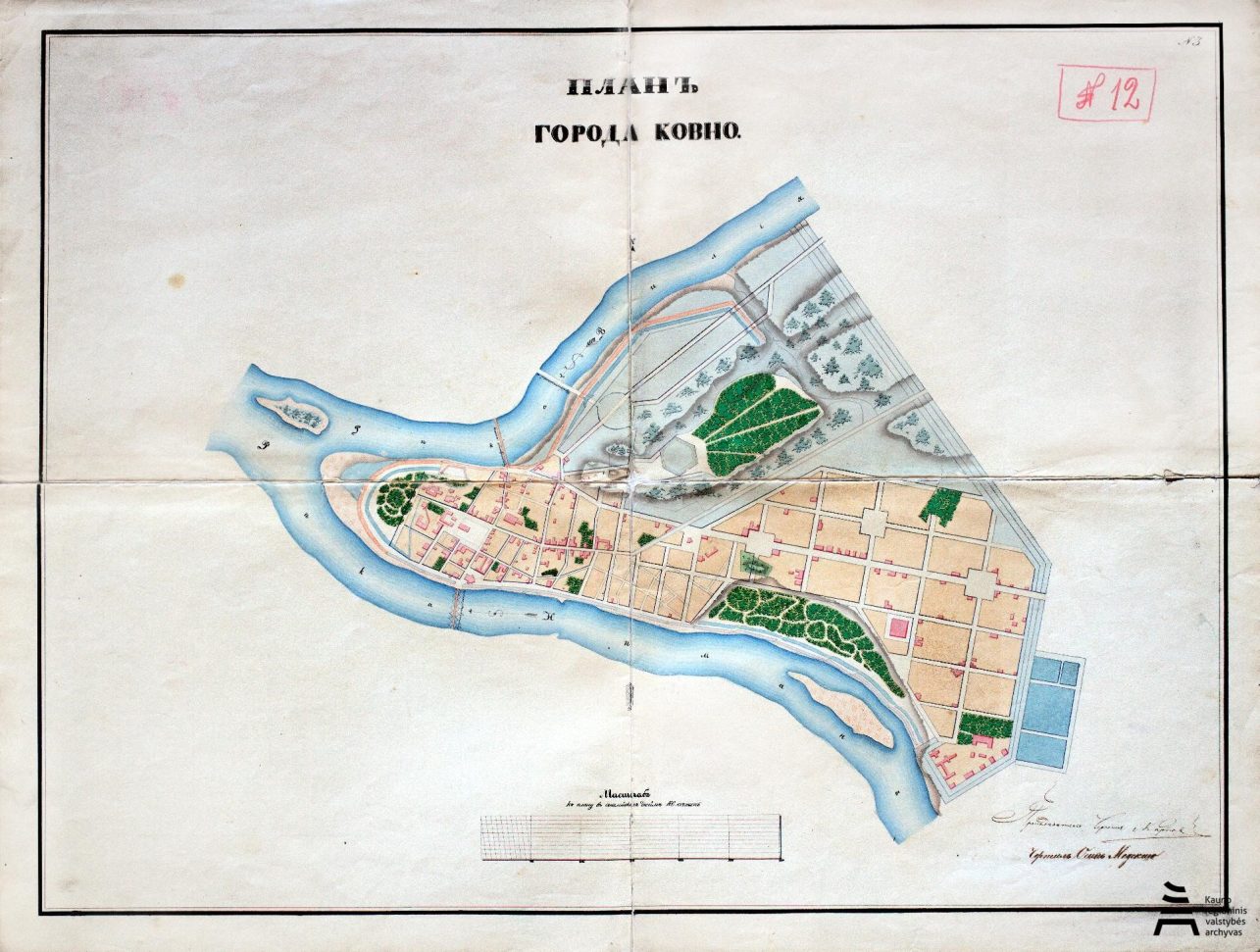

Essentially, Kaunas remained like this, with an area of just 1.5 square kilometers, until the next phase. For several centuries, due to natural geographical boundaries, the city remained clustered around the confluence of the rivers, where shipping routes and merchants’ paths intersected. The first city street network and urban fabric naturally formed along the quays, remaining unchanged until the mid-19th century.

Development under occupation and changes

In 1795, Kaunas became part of the Russian Empire. A somewhat more active phase of urbanization began, with the idea of a new town (Naujamiestis) slowly taking shape and several development plans being drawn up. According to the archivist, they were not realized but remained on paper: people continued to live as they did in the Old Town, while Kaunas moved forward slowly. There was no need for major changes.

“The situation changed dramatically in 1847 with the approval of a new Kaunas city development plan, when Kaunas became the center of the governorate,” the curator emphasizes. At that time, a new type of planned structure was established for central Kaunas, featuring a rectangular street grid – essentially the layout of Kaunas’ center as we know it today. The city began expanding eastward from what is now I. Kanto Street to the part of Ąžuolynas, later named Vytauto Park. At that time, the entire future territory of Kaunas’ New Town was covered by forests and sand dunes. In the spot where the Garrison Church now stands, there was once a swamp where ducks were hunted.

The project was prepared according to the so-called principles of Russian urban planning, without taking into account natural conditions. It is said that the layout of Kaunas, like that of many other cities, was adapted based on the planning principles of Odessa. This plan became a template for other cities across the Russian Empire – from the Caucasus to the Baltics.

“Three reference points emphasized back then have remained to this day. The current Vienybės Square, the city garden, and the Nepriklausomybės (Soboras) Square were already formed then,” the curator continues. These locations became city landmarks and spaces for national celebrations.

Construction of the Kaunas Fortress

Researchers of the past rightly say that at the end of the 19th century, Kaunas had slowed down. “On July 7, 1879, the Russian Emperor Alexander II approved the proposal of the military command to build a fortress in Kaunas. Kaunas was chosen because of the confluence of the Nemunas and Neris rivers as a barrier to enemy troops, the strategic importance of the railway bridge, tunnel, strategic roads, etc.,” the archivist notes.

Kaunas’s development came to a halt. Military needs were prioritized. This continued until 1915, when Russia’s defeat was already evident. Still, it was during this period that key urban planning decisions were made. The ones that determined not only the city’s main transportation routes but also the long-term development of nearby districts such as Šančiai.

Kaunas no longer grows naturally; it is confined within the fortress walls, fences, and moats, prepared for war. Yet, at the same time, hundreds – if not thousands – of new buildings are constructed. Numerous roads are built, which, in independent Lithuania, will become major transportation arteries, and the city naturally continues to grow around them.

The fortress’ street network included various types of roads, such as radial routes, bypasses, and specialized railways. The infrastructure and street layout were adapted to meet military needs, defense strategies, and logistics. Most of the roads were intended for transport and communication between forts and other fortifications.

I think that the fortress roads, i.e., the current streets, should have special markings so that we would understand the slow pace of the city’s transformation. That way, each day we might reflect while driving along K. Baršausko, Jonavos, Linkuvos streets, Rokai Road, or dozens of other Kaunas roads. And let’s not forget the famous “mother-in-law’s tongues” that twist around strategic locations.

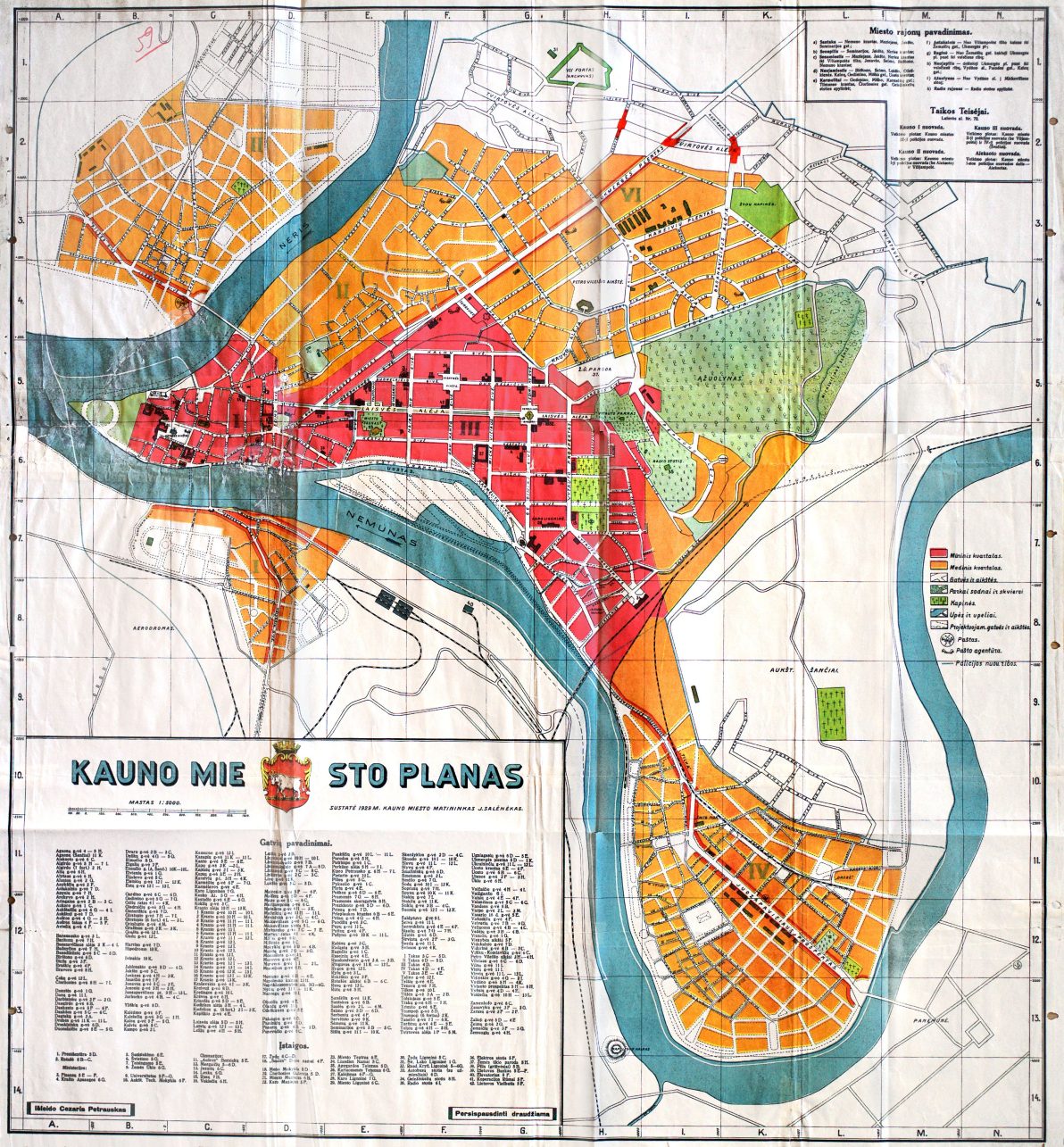

Golden era

No matter whom you ask – young or old – everyone will say that the best time for Kaunas was under Antanas Smetona. Public discourse certainly doesn’t lack praise for that era. The uniqueness of the period is further underscored by the recent inclusion of Kaunas modernism as a phenomenon in the UNESCO World Heritage list. In just two short decades, Kaunas transformed from a provincial town into a European capital.

The city grew faster than usual. It doubled in size. “The most obvious change was the Kaunas Development Plan created by A. Jokimas and A. Frandsen, with the still prestigious Žaliakalnis Trapezium district. Apart from the aforementioned annexed districts, this was probably the most significant change implemented in the city’s plan,” my interlocutor, Nijolė, says.

Unlike in the times of the Kaunas Governorate, in independent Lithuania, the city of Kaunas was planned to take into account the terrain, natural conditions, and other factors. The streets of Žaliakalnis fan out from the center upwards, adapting streets and plots to the slope. Almost the entire street network has remained unchanged for 100 years.

Streets remain, but names and numbers change

Every government tries to assert itself, to engage in collective consciousness control, ideological rewriting and historical revisionism. Older generations of Kaunas residents remember well the older street names, all of which were changed after independence.

Mindaugas Balkus, in his book How Kovno Became Kaunas, tells an interesting story about an even older and more interesting period of transformation. The names of many streets in Kaunas have changed at least four times since the beginning of the 20th century. And the numeration of houses changed only once, at least in the city center.

The history of the changed house numbers is truly interesting: the inventory was carried out in 1940, during the first Soviet occupation. It was done by none other than the senior students of the gymnasiums. This was even noted in the attendance registers: students were absent that day because they were inventorying buildings in Kaunas. The undertaking was enormous; all real estate larger than 220 square meters had to be nationalized. How else would you find out everything if there were no tax inspection records? So they used the cheapest literate workforce available.

All property plots were inventoried and recorded, and one plot could include more than one house and agricultural buildings. The purpose of the plots was actively changed, and new residential areas were created. Eventually, everything was sold out and divided into pieces, which is why some streets ended up with more house numbers.

Multi-layered and slow

On the way home, as I make my way through the winding fortress roads, bohemian modernist shop windows, and narrow medieval streets, I sit down and think: Kaunas has changed a lot. Yes, the city has certainly changed in 600 years. The only question is, how do we count that time ourselves – is that a big number or a small number for a city?

But maybe what’s important is not how much it has changed, but how much we want to see it. The Kaunas Regional State Archive is constantly opening its treasures to visitors who want to see history up close and through authentic artefacts. Not only through photographs, but also through maps and plans, from above and more slowly.