To experience the true pulse of contemporary art in Kaunas, one must wait for the right moments – Kaunas Biennial, the Audra festival – or, sometimes, when all expectations fade, an unexpected invitation might appear. A year ago, such an invitation came from the Heritage Institute collective, inviting visitors to a building designed by Stasys Kudokas in the old Kaunas cemetery for a science-fiction-themed weekend called Dūlà. The subject of this article, Mantas Valentukonis, once confided in me that he dreams of turning that cemetery administration building into an art gallery.

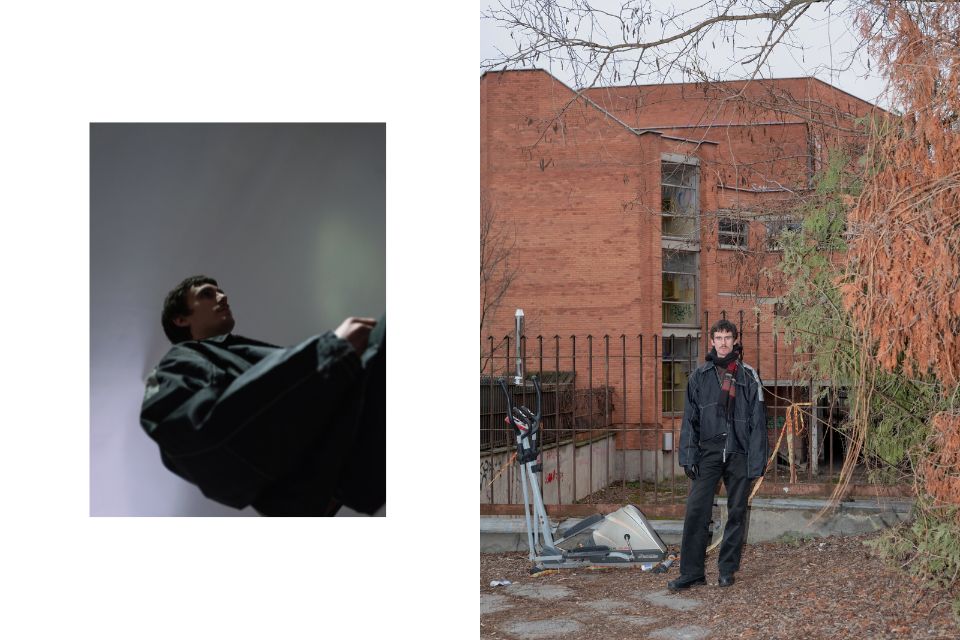

While his search for a permanent space continues, the exhibition he curated – Intermediate Glooms – became a striking highlight of early 2025. Exhibited throughout January at the Meno Parkas Gallery, it was there that I met with Mantas, who, at this point, should probably be described as a member of the younger generation of artists. In 2023, he completed a bachelor’s degree in painting at the Vilnius Academy of Arts Kaunas Faculty. His first solo exhibition took place in 2024 at Drifts Gallery in Vilnius, and he ended the year by installing a video game in the Sapieha Palace.

It’s 3 p.m. and you’re saying, “Good morning.” Do you work at night?

Yes, these days I spend many nights at the computer. I’m making an animation for the Audra festival. I take on commissions like this because it’s interesting to solve visual problems, and it’s not completely alien to my work. To create a painting, I need to know Photoshop and other image editing programs. Now that I’m creating video games, I need to know animation. It’s all connected and if it comes together, it makes sense to me.

You told me that you graduated from John Paul II gymnasium and then enrolled in business management studies. So, I understand that you are from Šilainiai, but you did not become a manager. Why?

Yeah, I live on Baltų Avenue, that’s where my flat and studio are. At school… these were strange times, a weird climate. After school, everybody enrolled somewhere, so I also went to study business management in England. It was convenient because my parents had emigrated there. I lived with them and went to that university, but I only managed to do it for four months. I came back to Lithuania, I met the art community, I liked the people, I felt like I belonged. I used to go to exhibitions, and painting impressed me the most. Just that image –paint on canvas. I took a couple of years of preparatory courses, made a portfolio, which I’m quite far away from now, and enrolled in the program. I had one choice written down – painting in Kaunas.

Did you ever doubt if you should have applied to Vilnius instead?

I did – many times. Of those four years of undergraduate studies, I probably only felt good for about half a year. The pandemic didn’t help either. But I applied because I was drawn to that former psychiatric hospital with its painterly atmosphere; those motifs just captivated me, and I thought about painting in a completely different way. But then they moved us out because the building was falling apart. We got new premises, but they were just… offices. I never really felt free there – it was intimidating to try and shape the space, and we weren’t allowed to drill into the walls or do much of anything. In general, the community in Kaunas is very tiny. When you go to Vilnius, you can feel the cultural pot boiling – there are so many galleries, artists, and activities. Here, it’s like everyone is on their own.

But you still live in Šilainiai. What keeps you here? Is it the thought, “If not me, then who?”

I’d like to think that, but honestly, I don’t really believe it myself. There has to be support and proper conditions – if those were in place, no one would want to leave the city. But right now, when there’s basically only one gallery in town… I don’t know, I really don’t. Yes, I like it here, I feel at home in Kaunas, but the conditions are tough.

What does your creative process look like? You mentioned video editing software, but at what stage are the canvas, sketches, and digital space?

After the JCDecaux exhibition (In the 9th exhibition organized by the Contemporary Art Centre together with JCDecaux Lithuania, JCDecaux Prize 2024: Autumn, Mantas presented a virtual reality simulation titled Quagmire, which functioned as an extension of sensory experience and created a favorable space for ambiguities to coexist – editor’s note), I stopped painting because I don’t know what to paint anymore. For that exhibition, I created a video game, which is a completely different medium than painting. And then the natural question arises – why paint at all? Sure, it’s enjoyable, the process is good, but so much has already been done in painting. It’s a very archaic medium. When making a game, so many more possibilities open up. What I want is to strive for something new, to discover. So, I no longer surprise myself with painting, and that worries me. But I hope I’ll get through this phase.

But if it’s about the process, then I usually get a sense of what I want to say, what character should be chosen for the painting, what mood, what symbol should speak about the whole situation. Then I create a digital sketch and start planning. I can’t go without a plan, and can’t just be expressive, except to paint the background.

We met at the Intermediate Glooms exhibition you curated, which was just a wonderful introduction to the year 2025. Why was it important for you to bring together artists from different generations working in different media? After all, it’s no longer a painting exhibition. I wonder what you had in mind when planning it.

Yes, there are a lot of static and dynamic images here. With professors and colleagues, we often thought about the idea of a moving painting – something that exists in space as an object but also moves, without being just a television. I wanted something like that, while also exploring painting in the context of today’s screen-filled life.

I think painting does a great job of representing and introducing a new layer of perceiving or capturing reality. It has a poetic quality, unlike the technological aesthetic, where everything is smooth, polished, and lacks depth. This contrast is beautifully revealed in Andrius Kviliūnas’ work, where he places himself – his very human presence – within the world of digital characters, highlighting the tension between the two. That’s what I was looking for – a middle ground between digitality and spirituality, painterliness, and humanity. I try to navigate between these two spaces myself, so I wanted to reflect that perspective in the exhibition as well.

It seems to me that by admitting that you are in a liminal state, you elevate yourself above the younger generation because the younger generation is already very comfortable in the digital space and is no longer nostalgic for the texture or the humanity you mentioned. Meanwhile, the older generation has no idea how it is possible to be without smelling, without touching.

Yes, I must be the middle generation now. I’m 26 (laughs), but I have a brother who is 21. Sometimes I think they’ve put another processor in him. I don’t do some things the way he does, but maybe it’s a character trait. For example, he allows himself to rest, to just be, and I always have to keep moving. I go, I want to do things, to say what’s on my mind. He doesn’t care about such things, and I find it beautiful. I would like to be able to just relax.

I remember as a child, my father used to take me to nature a lot, so that I wouldn’t sit so much in front of the computer. That means there was a conflict between digital and real. I still like nature, but I also like to take a computer with me [laughs].

I still hear the stereotype that artists are digitally illiterate, and you’re telling me how you made a video game for an exhibition. You do everything yourself; do you know how to write code?

Up to a certain point, but ChatGPT is a great help – it’s my companion, and I turn to it to save time, so I don’t have to write 40 lines of code myself.

And do you find the code itself visually pleasing?

Yes, yes. Code is a kind of poetry. On the ground floor of Meno parkas, there is a piece by Sandra Golubjevaitė – she wrote poetry by hand and created a device that captures the poetry with a camera, sends it to a program on a computer, and the program interprets the text and tries to replicate it. But it doesn’t see the text perfectly, there are reflections, so it generates complete abstractions.

How do you rate your experience as a curator? To what extent does Mantas the artist tries to influence the curator and to what extent does Mantas the curator try to control the artist in you?

I don’t know what it would be like to curate exhibitions on other topics, but for now, I am very interested in digital, and in curating an exhibition like this I am working through my own internal creative questions. In this way, creation and curation are intertwined, and this exhibition is partly another one of my creations. I tried to look at painting in it as a pause between moving images because people love paintings and screens are universal and anonymous. People love handmade things, which is what a painting is, and they can make them spiritual. I think if you love paintings, you love the artist.

Do you have favorite artworks by colleagues at home?

Yes, while I’m still young, I exchange artworks with everyone. Now I’m very fond of Gasparas Zondovas. I have a piece by Šarūnas Baltrukonis, and one by Gerda Malinauskaitė, who doesn’t paint anymore. I exchanged with Andrius Zakarauskas, who was my teacher. And I have a piece by Giedrė Mačiulaitytė from her summer practice: just a little man sitting in a tree. It is so memorable to me because it is not digital at all, it is sincere and pure. I also sometimes would like to just paint without much thought about those media, because the screen does not allow me to paint so freely.

What do you mean?

I seem to be used to a sharp outline. Just applying it with a brush doesn’t look good to me unless I treat the paint with additional means. Maybe I’m just used to a perfect image on the screen. It has to do with the mental state – we see spaces somewhere there, on the phone, but everything happens in the head. The same applies to painting. It seems that I must fix every little line to make it speak for itself.

You sound like a programmer: instead of letting go, you want to fix it. Does the desire not to leave things as they are push you forward or constrain you?

Yeah, I am a bit of a strategist. It seems like you’re always trying to improve yourself and you don’t paint because, well, you can’t yet. So, yes, it is constraining but I try to fight with myself and lower the bar and at the same time have more confidence in myself. Because you can’t make art if you don’t trust yourself.

What will your generation be called in 30 years?

I don’t know yet if we’re really making an impact or if we’ll just evaporate. I don’t know how it will be; I’m just trying to be honest.

instagram.com/valentukonis_