One Friday afternoon, I was taking a taxi to Klonio Street and looking out the window, thinking about how people feel when they visit other people’s homes for the first time. Are they wondering what kind of souvenirs the hosts would like, trying to remember if their socks had any holes in them, and worrying about common topics of conversation? At least I had solved the last puzzle, because when I went to meet the heroes of this article – photographer Teodoras Biliūnas and art historian and designer Kristina Šilinytė and their home – I was prepared with a bunch of questions.

As soon as I walk through the door and meet my hosts, my hesitation disappears and I am drawn into the bustle of the house: my coat is being hung, and they are looking for slippers for me, I am then escorted to the kitchen full of nose-tickling smells of cinnamon banana bread, and in the background of calm music, I greet the youngest family member – the couple’s daughter, Rusnė. Without further ado, Teodoras invites me on a tour of the house.

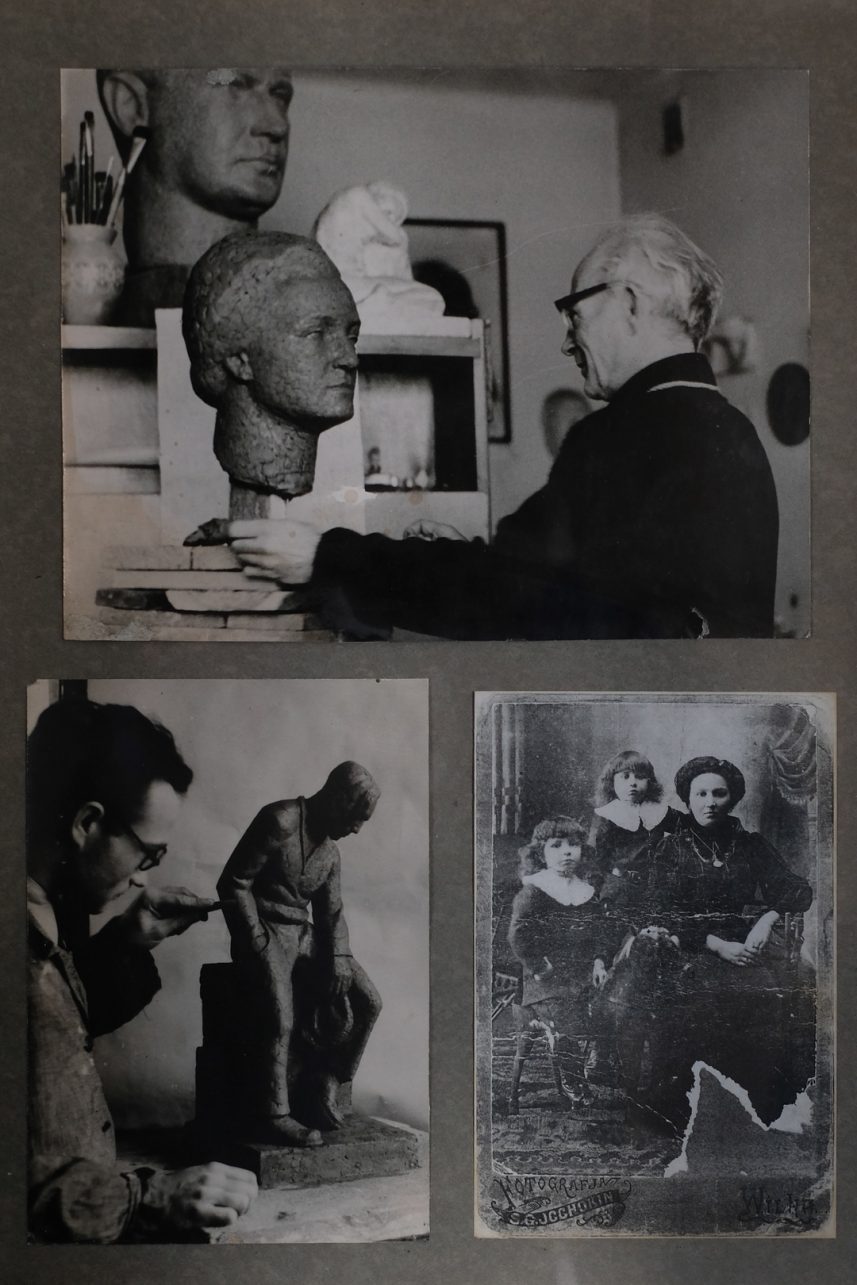

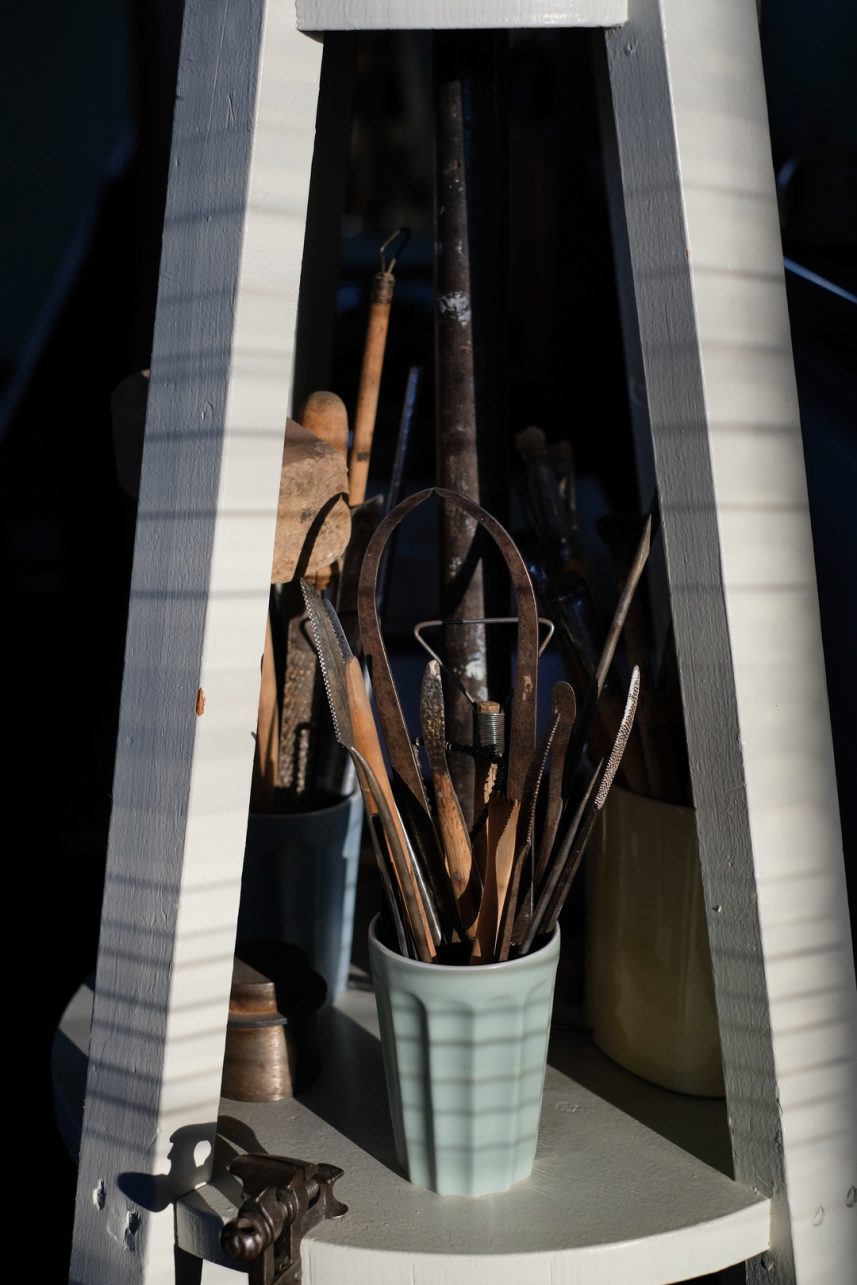

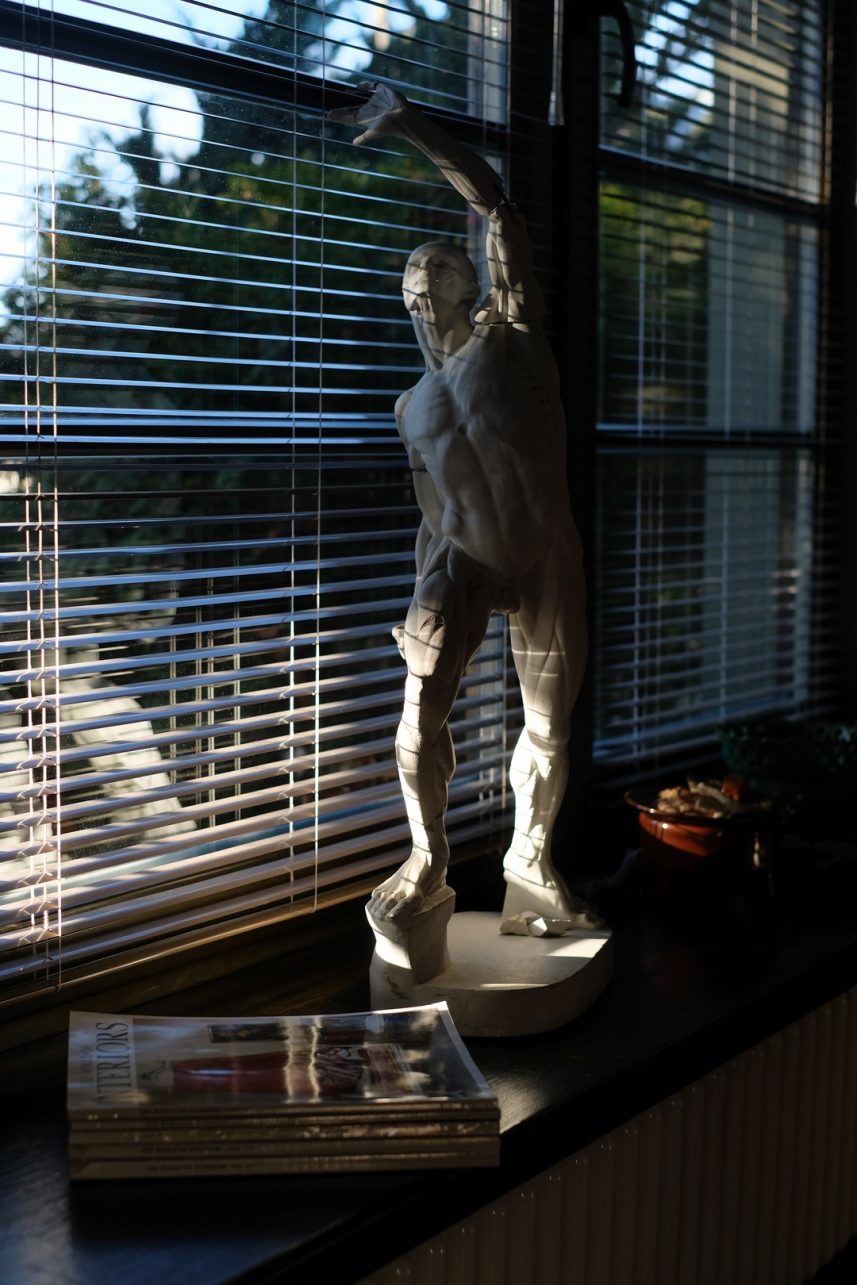

The spaces of the house, the interior, and the stories of the people who used to and still live here are fascinating. The house, built in 1959, is home to objects from the ancestral homestead of Katilius, the collection of grandparents and parents, and some of them purchased by Teodoras and Kristina. The house was continuously getting fuller and fuller, layer by layer turning into an organic whole. “When you step inside, you might think the home has always looked this way, but in reality, it has constantly evolved. The home is authentic; it hasn’t been preserved as a museum,” Kristina says, and Teodoras adds that every object in the house has a story. In the kitchen, my attention is immediately drawn to the interwar period cabinet and a large stove. Next to the kitchen is a spacious living room connected to what used to be Teodoras’s grandfather’s studio – artist, sculptor, and Professor Viktoras Palys. Teodoras points to the outline of an opening on the floor of the former studio: “The workshop that my grandfather needed was attached to the house. He would lift the lid and lower the heavy sculptures with the hoist directly into the basement.” This living room-studio space is truly impressive, and the abundance of objects is dazzling to the eye. Almost the entire wall space is covered with works by Teodoras’ grandfather and other artists. The shelves are filled with books and albums, and the room features several busts. Vases exchanged as gifts between Kristina and Teodoras’s mother, Rūta, adorn the windowsills. The room is furnished with massive wooden furniture. For instance, there’s a wardrobe dating back to Teodoras’ grandfather’s student days, and armchairs crafted by their former neighbor, Jonas Prapuolenis. On the table made in 1927 that belonged to Viktoras Palys, stands an old, corded telephone, with the interwar-era house number inscribed on its “belly”. Teodoras’ friend recently found the telephone in an antique shop, and so, after many years of wandering, it unexpectedly returned to its place on the table. Teodoras draws my attention to one of his grandfather’s most famous works, Sitting Girl, created in 1937, as well as bird taxidermy specimens from an expedition to South America, gifted by Tadas Ivanauskas.

We walk down the corridor toward the guest room, with Teodoras naming the artists whose paintings adorn the walls. Jokingly, I wonder if, with such a rich collection that doesn’t fit on the walls of their home, there’s still any desire to visit the Čiurlionis Museum. The topic of the museum came up several times during our meeting. Kristina mentioned that when people visit their home for the first time, they often call it a museum. I can understand that, especially for those accustomed to seeing sterile, minimalist interiors. I ask Teodoras whether there’s ever been a desire to exhibit part of the collection gathered by his grandparents and parents or to entrust it to a museum. “There was a lot of discussion and deliberation, but it’s best when all the objects, works, collections, even letters are in one place and complement each other.” The couple, however, are not ruling out the possibility of setting up a museum in their home and hosting people themselves. “When we get older,” Kristina adds.

On the second floor of the house, with another kitchen, several family rooms, and a guest room, we find a more restrained, minimalist version of this home, but it is also full of objects that tell stories. In the kitchen, there is an old stove that came from the village of Katiliškės and belonged to Teodoras’ great-grandparents. His grandmother kept it in the cellar of the house and used it to bake cakes and potato pudding. One of the most impressive finds is a painting by Leonardas Kazokas. It was hidden in a wall and now hangs in the guest room. An interwar period wardrobe inherited from the grandparents is still in excellent condition.

After the tour, I settle onto a massive moss-colored sofa in the living room. The room is lit by a crystal chandelier, the very same one featured in a 1982 documentary about artists of that era, including Viktoras Palys, who built this house. It seems fitting to begin the story with him, as understanding the people who created these layers is just as important as observing them. Viktoras Palys was an artist who graduated from the Kaunas Art School and studied law, though he never worked in that field. Teodoras shares that his grandfather studied in Estonia under sculptor Anton Starkopf from whom he learned to work with stone sculpture and was the only Lithuanian sculptor of the interwar period who worked professionally with marble. Viktoras met his future wife Magdalena Katiliūte, Teodoro’s grandmother, in Marijampolė, and then came to Kaunas to study together. Magdalena studied Lithuanian Studies and Philosophy at Vytautas Magnus University but eventually gave up her career, allowing her husband to work while she took care of the house and raised three children. She was interested in dendrology and horticulture and tended her home garden, which was voted the most beautiful in Kaunas in 1967. All three of the family’s children – twins Jurgis Rimvydas and Viktoras Vaidotas and the younger Rūta – chose to study architecture. The brothers left home quite early, while Teodoras’ mother Rūta continued to live there with her husband, physician Mykolas Biliūnas, after their wedding.

Teodoras was also born in this house. “My grandparents lived on the first floor until their passing, while my parents occupied the second floor. After my grandparents passed, my parents moved to the first floor, and we were given the entire second floor. This made creating our personal space easier, allowing us to design it in a more modern way,” Teodoras explains, noting that recently, he has started spending more time on the first floor. “Our daughter plans to use the kitchen on the second floor, so I understand that the time has come for us to move to the first floor,” Kristina laughs. She has lived in this house for over twenty years, having moved in after marrying Teodoras. The couple met while studying art history at Vytautas Magnus University and later worked together at a publishing company. They recall a humorous story about inviting colleagues to their wedding. Some of their coworkers were surprised, as they hadn’t realized the two were a couple, despite the fact they had been together for ten years.

I ask Kristina if this home has become her own. “I’m the kind of person who can create coziness anywhere,” she says, and I suspect that without knowing it, you might be creating the warmth of your home with Kristina’s help – she is responsible for the Native LT brand, which creates home decor inspired by Lithuanian nature and traditional crafts. I see a few of them in the couple’s home, of course. How do new things find their way into the interior? The family usually takes its time while looking for the right item and the purchase is deliberate. “When I buy a new item, I always think about whether my daughter would like to inherit it. She won’t necessarily want to when she grows up, but it helps to choose valuable things. I like heavy oak objects the most because they last a long time and are always stylish. I don’t have a need to update my home every ten or twenty years,” Kristina says.

It seems inevitable that being closely connected to past generations and preserving part of the interwar heritage also fosters a bond with the city. Teodoras openly admits to enjoying passionate discussions about Kaunas’ history and heritage. Kristina wrote her academic papers on private residential houses in Žaliakalnis, which deepened her love for the city. She contributed to preparing descriptions of objects in this area for the Cultural Heritage Register and organized tours in Šančiai, Panemunė, and Žaliakalnis back in the 2000s when such activities were neither popular nor common.

And what would their own home tell us about Kristina and Teodoras? “That we are like tramps, who also organize get-togethers on weekends,” Kristina laughs, adding that she often returns home only late at night. None of the people here, except for Teodoras’ dad, have ever worked a set schedule. “We’re quite inconsistent, but after the birth of our daughter and a bit more systematic rearrangement of our work, we became more sedentary,” he says. However, certain family traditions are continued and passed on from generation to generation. The house has always been bustling, and open to friends, a company of people and guests. “Grandfather was a very tidy, responsible man, but in the photos, I have often found him surrounded by company in this living room. I remember more than one occasion in my childhood when guests would arrive spontaneously, my mother would bake a potato pudding to feed a large group, and there would be people in the living room.”

Kristina adds that family and friends visit their house at least once a week. “My daughter’s friends can also come and stay overnight at any time, and we always have a set of bed linen ready.” Another tradition they have is decorating the eggs with wax on the Thursday before Easter. Over the years, a large archive of painted Easter eggs has been built and is constantly reviewed.

It’s getting late. Teodoras, who sees me through the door, adds that what really matters in this house is his grandparents and the preservation of their memory and legacy. When asked if this is out of a sense of duty, Teodoras hesitates a little, after all, it is just the way it is and the way it should be. I recall Kristina expressing concern during our conversation about the best way to pass on family values to their daughter, ensuring that the family’s legacy – both material and intangible – is cherished. I’m certain that this process is already underway – the couple leads by example, guided by a strong moral compass, preserving family memories, and respectfully and consciously building new layers atop the old ones. Generation after generation, by giving space to those who have lived here before, we invite them to stay forever and that’s an act of communion and care. Upon returning home, I thought that the longest and most meaningful tradition of this family is not just the ever-open doors or Easter egg decorating, but the preservation, cherishing, and continuation of the threads that connect the different generations.