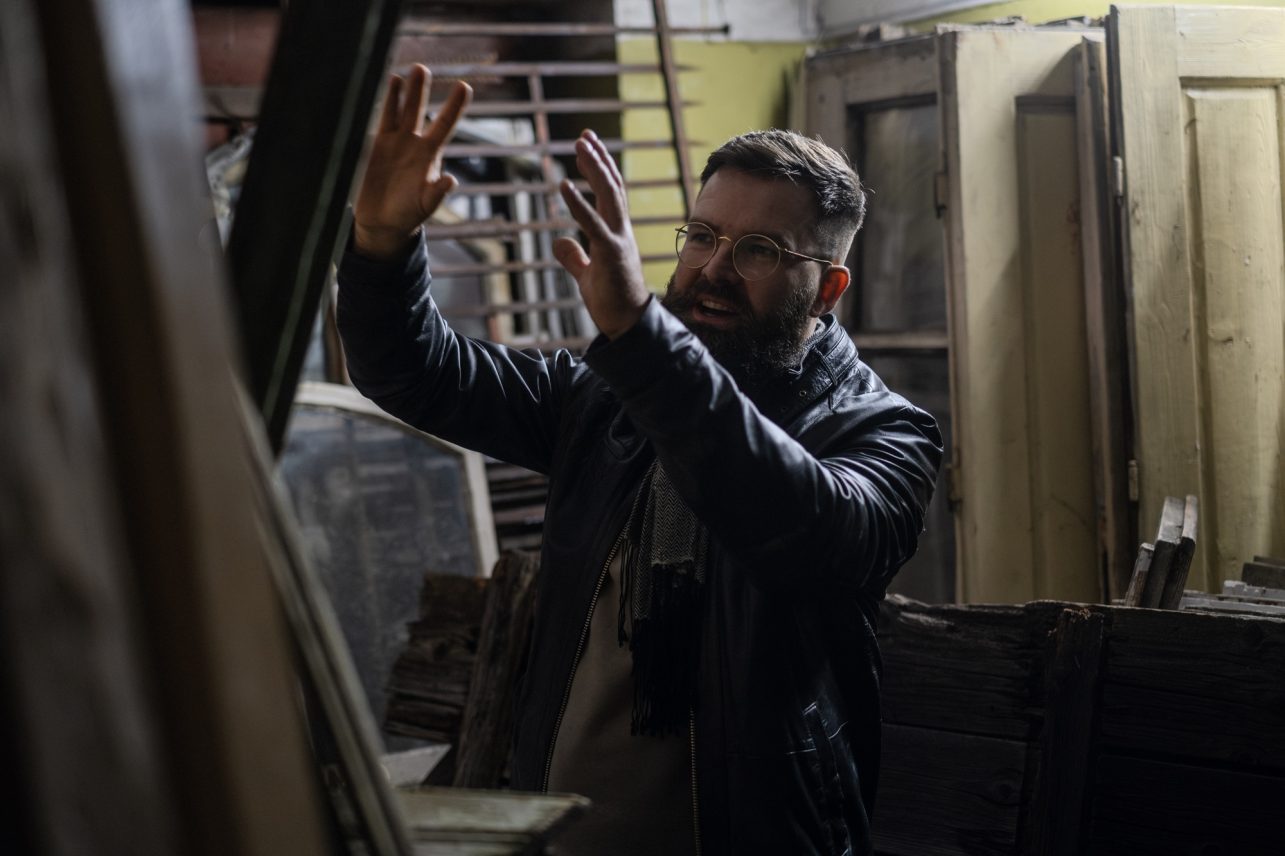

“My great-grandfather Kazys Kerpė was a civil servant, the governor of Marijampolė County, and when he retired, he decided to settle in Kaunas. It was expensive in the center, so he bought an unfinished wooden house in Žaliakalnis. He settled in one part, and rented out the other apartments,” Povilas Konkulevičius explains, jingling his keys. I think Mr. Kerpė would be surprised by how far the story of his investment went and how a simple wooden house inspired his great-grandson.

We’re at the territory of the Machine-tool factory in Kaunas, on Savanorių Avenue. Povilas rents a space here, which is stuffed with wooden doors, window frames, and other elements. On Dzūkų Street, where Mr. Kerpė once moved, there are two more garages, which are also stuffed to the brim.

Is Povilas overseeing a future museum? Perhaps not, as a brand-new institution dedicated to wooden architecture has just opened in the capital. However, Povilas has already established a public institution named Statybų kultūros fondas. Its purpose is not only to educate people about the wooden heritage, to protect the remaining examples of it from destruction, but also to nurture the tradition of craftsmanship and raise a generation of enthusiasts who know how to work with wood.

Povilas became famous among architecture enthusiasts, Kaunas historians, and residents of Žaliaklanis a few years ago, when he started talking about “the elephant in the room” – the disappearing wooden architecture. His foray into public activism was driven by personal experience: after inheriting his great-grandfather Kerpė’s house, he decided to restore it and quickly ran into obstacles. He couldn’t find craftsmen who knew how or wanted to work respectfully with historical wooden architecture. Living in Žaliakalnis, he couldn’t ignore the vanishing wooden heritage; once, he happened to pass by a house being dismantled on Minties Rato Street and brought home its light fixture. Soon, he started bringing back even larger items. One person’s trash is another man’s treasure.

As we talk, I realize that Povilas has the collector’s gene. He finds it hard to walk past anything of value. He recounts story after story about the treasures he’s gathered. For example, windows made from dense, high-quality wood salvaged during the restoration of the modernist Chamber of Agriculture building, “It would be great to make doors out of it!” I wonder if perhaps people are too lazy to restore the items as some of the pieces in Povilas’ storage look stunning even to an untrained eye. “Yes, people prefer new armored doors, but why? They have no value, and seem uninviting…”

Or he gestures toward nearly 3-meter-tall door: “From Vilnius, from the Merchant’s House. A woman contacted me, showed me a photo… I couldn’t pass them up. I hired someone to transport them from Vilnius, and then I spent about an hour inching them inside, millimeter by millimeter – they’re oak and incredibly heavy.” Some of the doors have been disassembled, their parts neatly cataloged, along with handles, hinges, and other details. We even examined elements of the staircase from the yellow house that stood at Minties Rato Street 37, adorned with carved tulips. “Damn it, they threw away those stairs! It wasn’t documented, and no one would know how beautiful they were if I hadn’t taken them”

But house elements are not postage stamps or matchbox labels, you cannot collect them by the million. There is obviously no more space. The question is what Povilas plans to do with his salvaged wooden elements.

“Recycling is certainly more active abroad, but here we don’t talk much about it yet. I’m really looking at it from a practical point of view. These pieces are a living example of how well things were built. You can see how the wood was joined, and what kinds of joints were used. From the preserved elements, you can create blueprints, then knives for cutting, and mill new elements in a workshop for a modern house whose owner values context and history,” Povilas explains.

According to the architect, a major problem is that modern woodworkers lack… craftsmanship when working with heritage. “We’ve heard and talked plenty about theory, but practice is a bigger challenge. In Japan, for example, craftsmanship is also considered heritage. Why can’t it be the same here?” he asks rhetorically.

“One of the doors in our house has unfortunately been replaced by a modern, plain one – my parents wanted to renew the home quickly. Only later did I realize we had destroyed a treasure, and that’s when I decided to restore it. But… how to restore it authentically, with joints and recessed hinges identical to the old ones? No one does that,” Povilas declares. He shares that he’s joined several Facebook groups about woodworking, where people often ask for replicas of old doors or windows. Craftsmen respond, saying, “Two smoke breaks, and it’ll be done.” “That’s when I join the conversation, and it turns out that no one will actually do it the way it needs to be done,” Povilas says.

For instance, in Kuldīga, Latvia – a city included in the UNESCO World Heritage List alongside Kaunas a year ago – the traditional craft is nurtured. Povilas dreams of visiting these neighboring hubs to learn how their craftsmen are trained and work and inviting them to Lithuania to share their experience and inspire others. With such knowledge, preserving the remaining wooden heritage in Kaunas and elsewhere in Lithuania would become much easier, and more people would be motivated to do it.

While fires periodically flare up in Žaliakalnis, and cement mixers quickly move into the emptied plots, one can only enviously read about inspiring examples abroad. France as a Guédelon Castle, a remarkable example of experimental archaeology. “The experiment has been ongoing for 25 years. They’re essentially building a medieval castle using old technologies. The idea is so popular that the project sustains itself, with people volunteering to participate in the construction,” Povilas says, clearly impressed. The knowledge gained from the Guédelon project was instrumental in the restoration of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, which was damaged by fire.

An important fact in Povilas’ biography is that he himself is an architect who studied at the Kaunas University of Technology. I asked him how much he heard about wooden architecture during his studies. “That’s a good question. We have lost a lot because architecture studies are based on modern architecture. Jonas Miknevičius (the legendary professor emeritus, who turned 95 this year and presented a new book on his birthday, ed.) taught history of architecture, 6 credits, and that was it, expression, forms, individuality,” the Kaunas resident recalls.

According to Povilas, this educational gap is plainly visible: architects in Lithuania working in historic areas often fail to rein in their ambitions: “And how could you manage them if you’ve never been properly introduced to heritage?” We agree that in the future, the foundation Povilas is just beginning to build could play a role in educating future architects and students in related fields. Naturally, it would also welcome “regular” wooden house owners who need assistance or knowledge.

For now, the Statybų kultūros fondas is a hobby for Povilas, albeit one that demands a lot of time. It’s intriguing to consider how much this passion influences his daily design work. Does paying closer attention to his living environment make it easier for him to balance those creative ambitions?

“First of all, it’s a very enjoyable hobby for an architect, because what others see as just scrap metal is an inexhaustible treasure trove of inspiration for me. And I will be honest, my attitude towards contemporary architecture has really changed,” Povilas says. According to him, this is not an easy shift because modern people are “dominated by minimalism.” He speaks enthusiastically about amateur architecture, an example of which is Mr. Kerpė’s house. “It’s not modernism – the house has column imitations, capitals. I’d say it coexisted alongside modern architecture during the interwar period. Maybe something similar could exist today? Perhaps we could not only cherish high-end architecture but also draw inspiration from traditional architecture”

The Kaunas 2022 program Modernism for the Future has ended, and the National Architecture Institute is still in development. For now, wooden architecture enthusiasts in Kaunas lack a dedicated space where they can meet regularly, discuss, learn, or perhaps even engage in the practical work Povilas envisions. The architect invites those who believe in his idea and know how to expand or improve it to get in touch – or even support the emerging foundation on the Contribee platform. Simply search for Statybų kultūros fondas in the search bar.