“I don’t know for sure,” Kaunas resident Aleksas Avalasevičius says when asked whether his home is in Žaliakalnis or Eiguliai, as he leads the way to the second floor of his small house, which he uses for his hobby that is much more than a leisure activity. He adds that he hasn’t been living here long – “only” 17 years! It is not enough to call this Kaunas native from Šančiai a collector: he is a phillumenist. Greek and Latin experts tell us that he is a lover of light. But actually, he simply loves matchbox labels. He has been an enthusiast for over 60 years, ever since he was a little boy, who would find matchboxes lying around while playing outside.

Matches as we know them have not yet celebrated their 200th birthday, and enthusiasts have been collecting their box labels for the same amount of time. Although, of course, there were fire-lighting thingies similar to modern matches in ancient China. It took centuries and stubbornness to develop a convenient, as safe as possible and yet affordable object, and when it was finally achieved, the Swedes had a monopoly. Of course, factories started springing up everywhere, including Lithuania, which was then part of the Russian Empire.

When we talk about the history of matches in Kaunas, we usually refer to the Liepsna factory that began operating in 1927 as the Joint Stock Company of Lithuanian matches. But the story is much older. The first match producers started their activities in Kaunas and around it back in the 1850s. The factories of that time had excellent names: Balkan in Žaliakalnis and Etna in Vilijampolė. Of course, these were small enterprises, not comparable to the companies that started operating during the First Republic, including the one that became Liepsna after nationalization a couple of decades later. During the interwar period, the Swedes moved in introducing a monopoly in Lithuania and significantly raising the price of matches, which were essential for ordinary people at that time. The matches, usually made of aspen, were often divided in half so that a box would last longer…

According to statistics, the factory on Raudondvario Road produced 257 million boxes of matches in 1962. Of course, it was not just for us – a lot was exported, for example, to Hungary. Aleksas has a lot of such Lithuanian Hungarian labels. Later, production volumes declined, and after 1990, Liepsna could not withstand the vicissitudes of privatization. However, the label lasted longer than the factory itself. Aleksas’ eyes – he is a real detective when it comes to finding inconsistencies, rarities, and curiosities – light up when he shows a clipping from a newspaper where a call to “buy a Lithuanian product” is illustrated with a photograph of a matchbox, however, the matches are actually made in India and only imported to Lithuania. Today, the site of Liepsna is merely a grocery store, where you can of course buy the imported matches.

I am also curious to hear how collectors living in different parts of the world communicate and whether they exchange labels. The solution is simple: correspondence. It is true that when Aleksas was collecting more actively, that “world” was limited by the Iron Curtain, so the new objects for his collection came from the so-called friendly republics.

Of course, you can’t build a two-million-piece collection just through letters. Therefore, every self-respecting phillumenist had connections in match factories. So, the foundation of Aleksas’ collection does not consist of loose labels (and certainly not those taken off matchboxes), but large uncut sheets that came almost directly from the Liepsna factory. “They used to print in a printing house belonging to the association, take it to Liepsna, and cut it there,” says Asta, Aleksas’ daughter and helper, who drops by the room. “Yes, Romas used to cut it,” he remembers an acquaintance and they both laugh.

Of course, the most fascinating thing is not the number of identical labels. It’s the differences that are barely visible to the naked eye, due to the mechanical work of the machines, the quality of the inks, the human hand… Thus, the same label can have dozens of variations, which will be appreciated, of course, only by people like Aleksas.

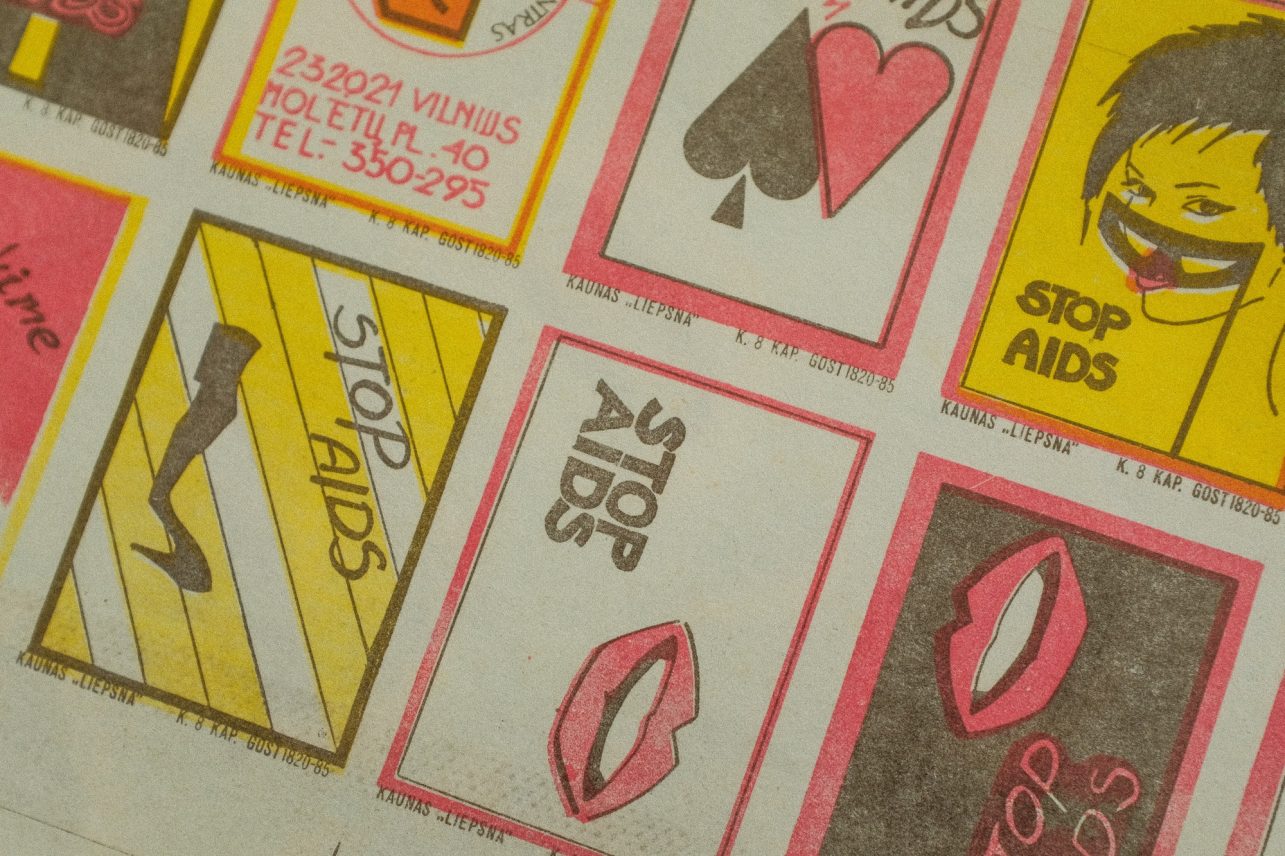

Just before we popped by the collector’s house, a letter from Estonia was dropped into his mailbox: an old colleague had sent new labels, but Aleksas mercilessly criticized the quality and aesthetics of the print. In fact, looking at the labels produced in the 20th century, one has to admit that some of them are true graphic design masterpieces. Of course, not all matchboxes are designed for the ordinary citizen who wants to light a cigarette or a stove. A great many so-called souvenirs were produced, the labels of which presented, for example, the most beautiful views of Kaunas and other cities.

It is also interesting to explore how the quality of paper and printing, the themes of the drawings (and later photographs), and the symbolism are related to the times and systems. It may be hard to believe now, but during the occupation, even such an innocent-looking object as a matchbox label had to meet ideological requirements. Anything could be criticized by decision-makers. Of course, you had to see samples of the labels to decide. Guess if Aleksas has any of those test labels that were never put on sale? Of course, he does. He shows it to us: an apple with a worm, which for some reason did not pass the censorship.

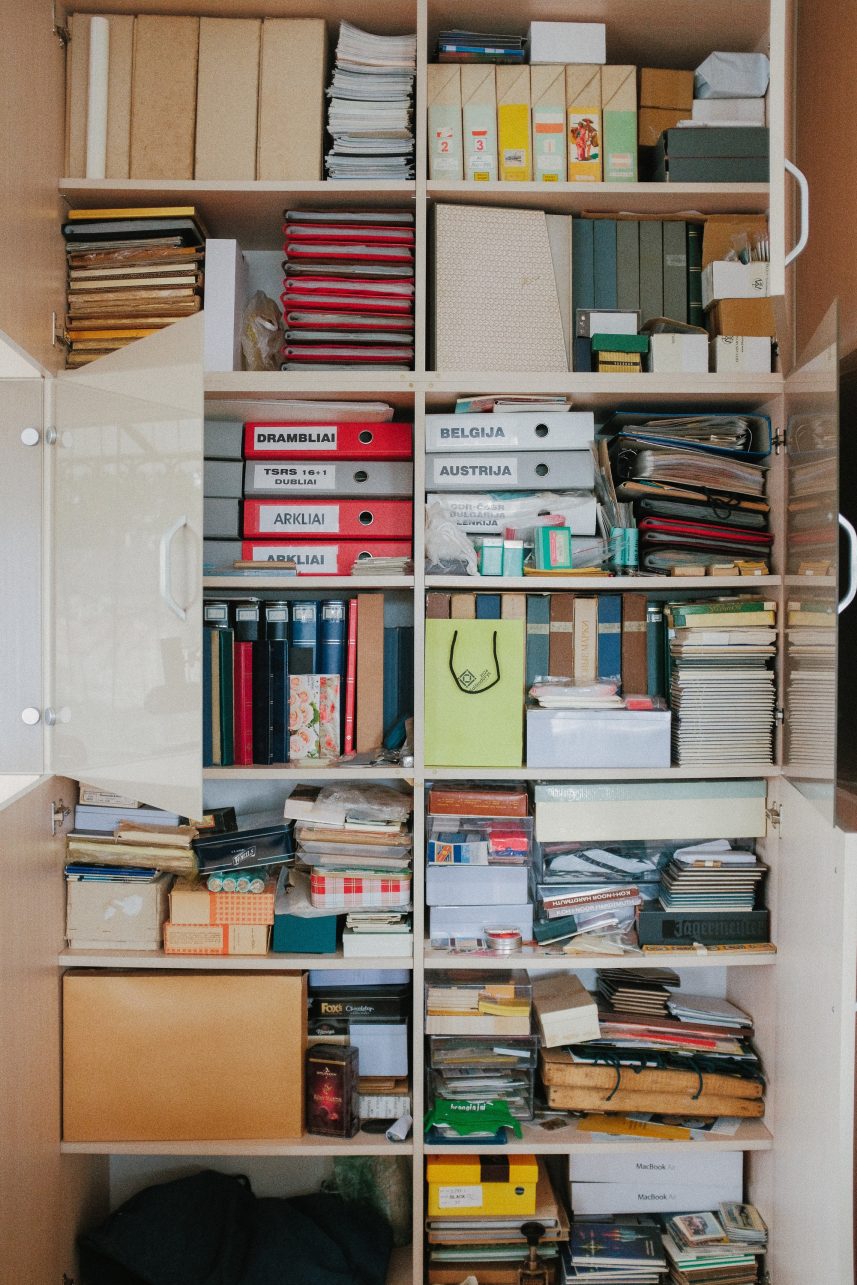

The collection of 2 million labels is certainly not limited to Lithuanian labels or labels produced in the former Soviet Union. There are many exotic ones: non-existent countries, Vietnam, China, and India. Some wealthier Chinese people travel around the world looking to buy their countrymen’s works, but Aleksas has kept some items for himself. Among the quite unexpected yet very logical items in the collection are ice cream sticks and other wooden objects, which, when you think about it, are quite convenient to produce at a match factory.

Propaganda slogans, fire safety warnings (or even AIDS awareness), flora and fauna, architectural sites, commercial advertisements, abstract drawings – essentially anything can be printed on a matchbox label.

Looking through the albums, lifting boxes, turning rolls, laughing, diving into nostalgia, and getting uncomfortable with politically incorrect (hint – both red and brown) labels, it appears that this man has everything. He would like to, but he is also well aware that this is not possible.

“I have bought the collections of almost all the people from Kaunas. There was only one person I didn’t buy from – Judelevičius, who used to draw the labels himself; Sprindys and Šepkus also drew them. The labels designed by these people from Kaunas were the best and the most beautiful,” Aleksas maintains and regretfully points out that now no one draws or prints labels. He can buy a collection of 12,000 labels just for the one he really needs, “I burned most of them, they were worthless.”

Interestingly, Aleksas doesn’t keep any catalog of his collection, and he does not write down when he bought what. “I keep it all in my head,” he says. As he prepares to celebrate his 74th birthday, Aleksas is full of energy, especially when talking about his collection. He laughs that maybe the fact that he likes sudoku helps him to stay young. Although, I think the hobby and the tons of information he holds in his head also play a big role. When asked what he did before retiring, Aleksas is somewhat modest, but he finally tells me that he worked in an advertising company for a couple of decades. It turns out that he made the boxes he needed to store his collection!

The conversation turns to the situation of phillumeny in Lithuania. The number of collectors is decreasing… Moreover, there is no such thing as a publicly available catalog of Lithuanian labels. Aleksas laughs that enthusiasts have been trying to create one for several years, but the ugly truth is that the largest collection of Lithuanian labels is kept in a museum in Moscow. Of course, he has a lot himself, but not everything. Sometimes he shows a small part of what he has accumulated in exhibitions. The Kaunas City Museum held one about a decade ago, and this fall, the Kaunas resident was invited by collectors from Kaišiadorys.

The hero of this article was considering setting up a museum of matchbox labels in his former family home in Šančiai. But… he doesn’t think it’s viable. If you think otherwise and have something to offer Alex, please get in touch! It would be a shame if such an interesting collection of ideologies, graphic design, printing technologies, and many other aspects remained in the closets somewhere between Eiguliai and Žaliakalnis.