Imagine your grandfather or great-grandfather was a KGB agent or a predator of a similar kind. It is a fact that the ancestors of some modern Lithuanians have written themselves into the list of bad guys by their actions. However, it takes work to talk about this in public. But it is possible. After all, we are not responsible for our ancestors’ deeds. Clemens von Wedemeyer, a German video artist whose work explores power structures and other social issues, had a grandfather who was a Wehrmacht officer during WW2. He also carried a 16 mm camera with him.

I met Clemens von Wedemeyer this summer. We both visited the Kaunas Ninth Fort Museum for the opening of the exhibition “BakhmutBakhmut. The Faces of Genocide 1942 | 2022”. Brought from Ukraine, it aims to draw parallels between the tragedy of the Holocaust, when over 3,000 innocent civilians, mostly Jews, were murdered in Bakhmut (Artemovsk) in 1942, and the Russian destruction of the city between 2022 and 2023. “This exhibition reveals the history of two genocides, separated by eight decades, but both perpetrated by repressive regimes: Nazi Germany and modern Russia,” reads the annotation.

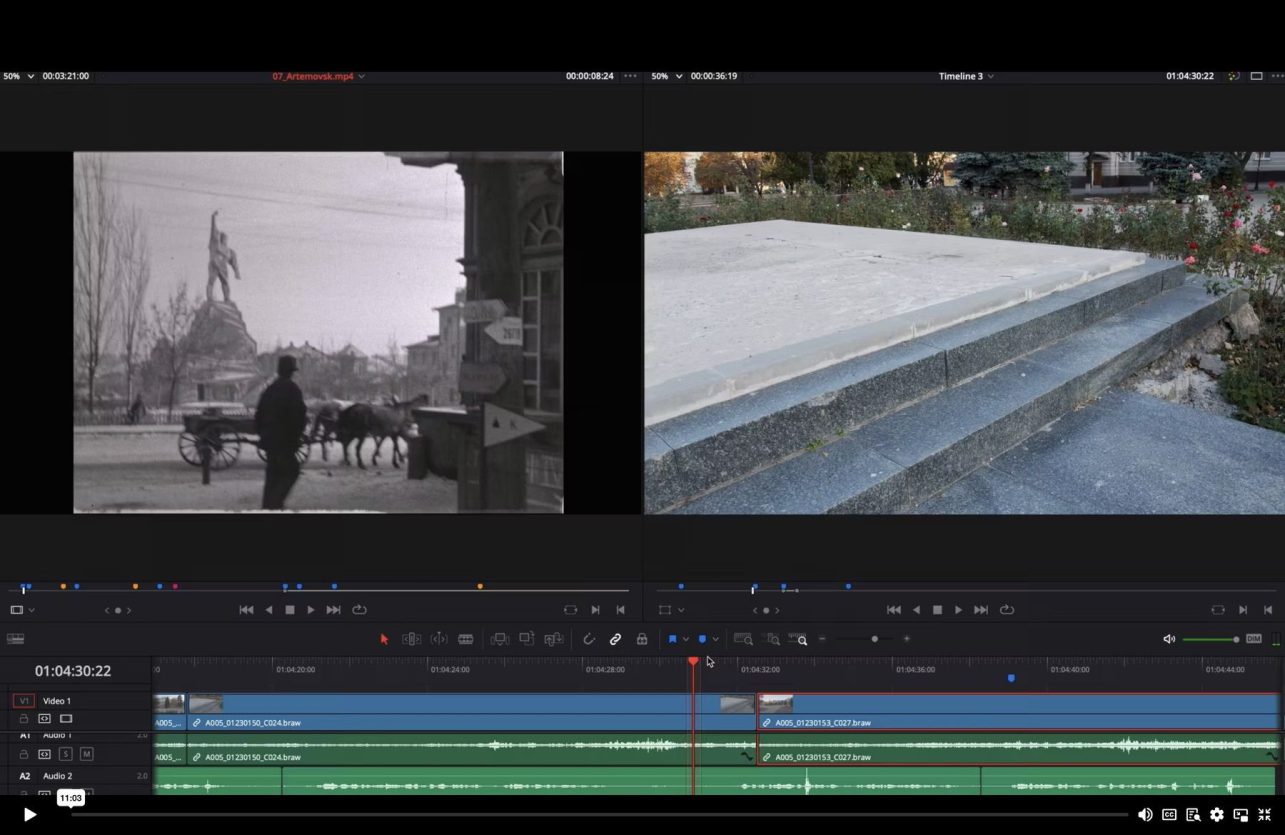

The curator of the exhibition, Mariia Mizina (Babin Yar National Historical and Memorial Reserve), not only included works by Ukrainian artists and photojournalists and some historical material but also C. von Wedemeyer’s video Bakhmut 2023 (11 min.), which juxtaposes the images of the same city taken by his grandfather and by the artist, as well as more recent documentary material.

Clemens, could you tell me about the prehistory of this work? Have you always known about the footage that your grandfather filmed in Artemovsk?

I never met my grandfather. Also, my mother is adopted, so there’s no direct line. I had access to the archive of these films made during the war in France, Holland, Poland and Ukraine, mostly. My mother gave the material to the Federal Archives of Germany and showed the films to historians who came to our house. So, I remember that I saw them at a very early age and that it also made some impression on me because it was 16mm and this old technology, but it took a long time until… I knew I wanted to do something with this material but needed time to deal with it.

It takes time to mature as an artist and be able to work with such sensitive material, am I right?

The material was first conceived for an exhibition in Berlin, and it’s a seven-channel installation. There are seven different ways of dealing with the material: essays, films, interviews, and a reconstruction of the scene in a 3D computer game environment.

I used a forensic approach. And yes, I think I needed some time to develop a non-ideological approach to film history, which I also used in some other works.

What was your reaction when you were invited to Bakhmut? Or were you looking for ways to go to the city and see what your grandfather saw in a different light?

At first, I didn’t want to go because I didn’t want to go in the footsteps of my grandfather and kind of follow the traces of crimes somehow. So, I was a little bit afraid of going. But then, with the invitation of a Ukrainian artist and curator, I felt like I was in a very good environment and decided to show this material directly in Bakhmut. I also learned they already knew about this material and held an exhibition about the German occupation some years ago. So, some of my fears or my preconceptions were misleading. It was a chance for me to also go to Ukraine for the first time because Ukraine was not on the map in Germany for many years, especially when I was in school. It didn’t exist, really. And then, of course, it became more present. And this is kind of a symptom of many people, especially from Germany, that didn’t care so much about Ukraine or other countries, let’s say, between Germany and Russia.

The situation in Bakhmut today is very different from what you filmed. So, the material became of archival importance. Did you have this archival layer in mind when you were shooting this material?

I just took my camera with me, but I still needed to decide whether I wanted to film anything in Bakhmut. I’m now lucky or happy that I did it, but I didn’t have anything in mind. I knew that if I shot something, I would try to look for the angles or places where the films had been shot, but I didn’t have a specific project in mind because the project was already kind of closed. But, yeah, we found out that it isn’t locked.

Many people who spoke in today’s opening mentioned retrospectives and the repetitiveness of anger or evil. What do you think is the role of artists and historians in this cycle?

Of course, I believe in cultural exchange and in preserving memory. Looking at memory gives a better understanding. I think it’s necessary to rework images and to keep archives alive. That’s very important. It’s challenging to compare history, but I think one needs to have a tool to understand the present at least a bit more.

You mentioned that you wanted to somehow remove the ideological layer from video material. Today’s event turned out quite political, as we have the parliament election in a few months. Is there space for politics in such exhibitions?

That’s a problematic question and a problematic issue because I think it’s not so helpful to politicize everything. But at the same time, I mean, this is a very political show, and also, this is an exception for me to put a work into a, let’s say, political show because I think it’s a historical political show. My work here is quite essayistic, and the boundaries are a bit open. But from my point of view, art is always somehow political, even if it tries not to be political. That’s also a political step to get out of daily politics and ideologies and to make things more complicated. You have been a significant artist for quite some time now.

How has working with material from Bakhmut influenced you?

I’m always looking at, let’s say, daily images or things that happen around me. The question is, when do you do something out of it? Here, I just felt the necessity of working on these images. Otherwise, if I hadn’t been asked, for example, also by a Ukrainian exhibition in Berlin in the beginning, to propose something, I wouldn’t have looked at the images again so fast. But I felt the need to do something. So the urgency is there, and so is the threat of forgetting. It hasn’t changed so much, actually. But what has changed is the urgency.