One begins to wonder at memorable dates and occasions: what was the everyday life behind the great events that changed the course of history? The year 1922 was important for education, art, law and finance in Lithuania but, for example, what were the parents of its future students doing when the university was being founded?

As always, the answers to the strangest questions about Kaunas can be found at the reading room dedicated to Kaunas, which is part of the Documentary Heritage Research and Promotion Center of Kaunas County Public Library. Senior bibliographer Mindaugas Balkus has advised me on street name change, and last year he published a book with Feliksas Zinevičius called Vladas Putvinskis’ Street: Historical Facts and Memoirs (Vlado Putvinskio gatvė: istoriniai faktai ir atsiminimai). By the way, V. Putvinskio Street was not there yet in 1922! More precisely, there was a street only it was first called Gornaja, after that Bergstrasse and when Lithuania became independent it was called Kalnų. And only in 1931 it was named in the honor of the founder of the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union, who spent the last month of his life in A. Žmuidzinavičius’ house (located on the same street), at his sister’s, who was the painters’ wife. But this is another year and another story! With M. Balkus we looked at the archives of 1922. And if you keep wondering about a specific street, sign, or year, you are always welcome to visit the reading room dedicated to Kaunas.

Speaking of the period of the First Republic, we often imagine the “interwar period” in a very general way. But the truth is perhaps such that the 1930s and perhaps the very end of the 1920s were considered the golden age of the temporary capital. Can we say that the year 1922 was just the beginning?

1922 was not the year of the beginning. The year when it all began was 1919, when Kaunas became the de facto temporary capital of the country because the central authorities of the Lithuanian state moved to the city. 1922 was the “year of gear change.” Kaunas moved from the post-war turmoil to the recovery period. 1922 was the year when the Constituent Seimas completed its work, the first Seimas was elected, the national currency (litas) was introduced, the university of Lithuania was established. Lithuania was also recognized by many important European and world countries, and their permanent diplomatic missions were established in Kaunas.

I would say that the temporary capital’s golden period was the end of the 1930s, when the face of the city (in terms of infrastructure) had been significantly renewed (water supply, sewerage, modern bridges were built, many streets were fixed, etc.) modern Lithuanian culture was the dominant one in the society. The city was inhabited by people of different nationalities with more than a dozen schools for ethnic minorities as well as various cultural institutions. And, most importantly, peaceful and constructive relations prevailed in this multicultural community of the temporary capital.

What did Laisvės Avenue look like in 1922? Today, we cannot imagine it without Pienocentras or the Central Post Office that were built a bit later. Was it a street of businesses and institutions, as it is today?

Laisvės Avenue was full of people, transport (mostly powered by one or more horses, there were still very few cars in the city). The street was paved with simple cobblestones, there were grooves on its sides to drain rainwater (there was no centralized sewerage system yet), and there were small wooden “bridges” above these grooves every few meters to the sidewalk, which was often lined with boards. There were linden trees growing in the middle of the street (just like today) and it was separated by rows of wooden stakes on either side. A pedestrian alley was formed between the linden trees with wooden benches (without backs). A horse-drawn tram (konkė) ran through Laisvės Avenue. The street did not smell of luxury at all.

Laisvės Avenue was full of various business establishments (shops, cafes, hotels, various offices, etc.) in 1922. Many languages were spoken on this street. In addition to Lithuanian, Russian, Polish and Yiddish languages were widely used. Signs of private institutions were usually written in several languages. Lithuanian was in a largest font (often with mistakes) and Polish and Yiddish were in a smaller one. The trilingual signs were completely legal in 1922. Later, at the end of 1920s, Lithuanian lettering prevailed, as the use of foreign languages in public signs was restricted by new regulations.

What was the average Kaunas resident like? Was it a newcomer Lithuanian (if it was already “fashionable” to move to Kaunas, the capital, at the time) or was it someone of the old generation, of Polish or Jewish origin?

In 1922, Kaunas was a multinational and multicultural city. The general census of Kaunas city and suburban residents was commissioned and carried out by the Kaunas City Board on June 1 of the same year. According to the data, Kaunas had a population of 84,352, of which 41,088 were Lithuanians (48.7%), 27,228 Jews (32.3%), 8,311 Poles (9.9%), 4,174 Germans (4.9%), 2,345 Russians (2.8%), 808 Belarussians (1%), and 398 (0.5%) of other nationalities. Thus, about half of the residents of Kaunas at that time considered themselves Lithuanian. It is probable that more than half of Lithuanians in 1918–1922 had arrived in Kaunas from other parts of Lithuania. They studied here as well as looked for work. There were very few people born and raised in Kaunas at the time. The old inhabitants of Kaunas, who lived here before the First World War, were mostly Jews and Poles.

In the interwar period, there were many more cinemas in Kaunas than today. However, the first Lithuanian film is only 90 years old. So, what did the repertoire mostly consist of in 1922?

There were 5 cinemas in Kaunas and its suburbs. They were all set up in the premises that were not suited for cinemas. The film theatres were dominated by American and German silent films. According to the rules at the time, the subtitles of the films had to be Lithuanian, and subtitles in other languages (mostly Russian) could be added bellow. In practice, however, Lithuanian subtitles were often accompanied by major grammatical errors. At the time, cinemas mostly showed rather simple entertaining films, with one or two of an erotic nature. They usually outraged the Catholic society because minors often tried to get in to see these films.

Could the average resident of the capital afford such entertainment as cinema, restaurant, and finally a vacation in 1922? At that time, we already “had” Palanga and Šventoji, but were they accessible to working class people, public servants?

Cinema as an entertainment was one of the most affordable for the masses, tickets were not expensive. At that time, there were good restaurants in Kaunas (Metropolis, Versalis), but the prices were high and ordinary people of Kaunas could not afford to taste the menu. Only the upper classes could afford a holiday at the seaside resorts. Lithuania acquired Palanga in 1921, when it signed a convention on the establishment of the Lithuanian-Latvian border. At that time, the tourism and leisure infrastructure in Palanga and Šventoji was not well developed and Palanga had not yet recovered after the 1915 bombing. In addition, it was difficult to travel from Kaunas to the Lithuanian coast at that time because there were no good roads. Aukštoji Panemunė or Lampėdžiai resorts did not exist yet and Birštonas did have a certain resort infrastructure, but it was also affected during the First World War. It is worth noting that in 1922 Klaipėda Region still did not belong to Lithuania. At the time it was administered by France.

What did the family pantry and the dinner table look like back then? There were no joint meat, dairy companies or store chains, so maybe the selection in the stores wasn’t that great?

There was a so-called “apartment crisis” in Kaunas in 1922. There was a great shortage of housing in the city and the rent prices had gone up, so very often several families lived in one modest apartment. The family table and the delicacies on it depended on social status. The richer ones could afford a more varied diet, more meat dishes, more different fruits and vegetables. Most families bought food in markets, less often in stores. Wealthier families had a maid who bought food at markets or elsewhere, brought water from rivers or wells (there was no water supply yet), tidied up the house, and washed the clothes. In the families of workers and civil servants, the household was mostly cared for by women in the family. The lunch table of working families was more modest, dominated by dishes made from cheaper products (potatoes, groats, etc.). Those with close relatives in villages around Kaunas had an easier access to food: they brought vegetables, meat and other products from there.

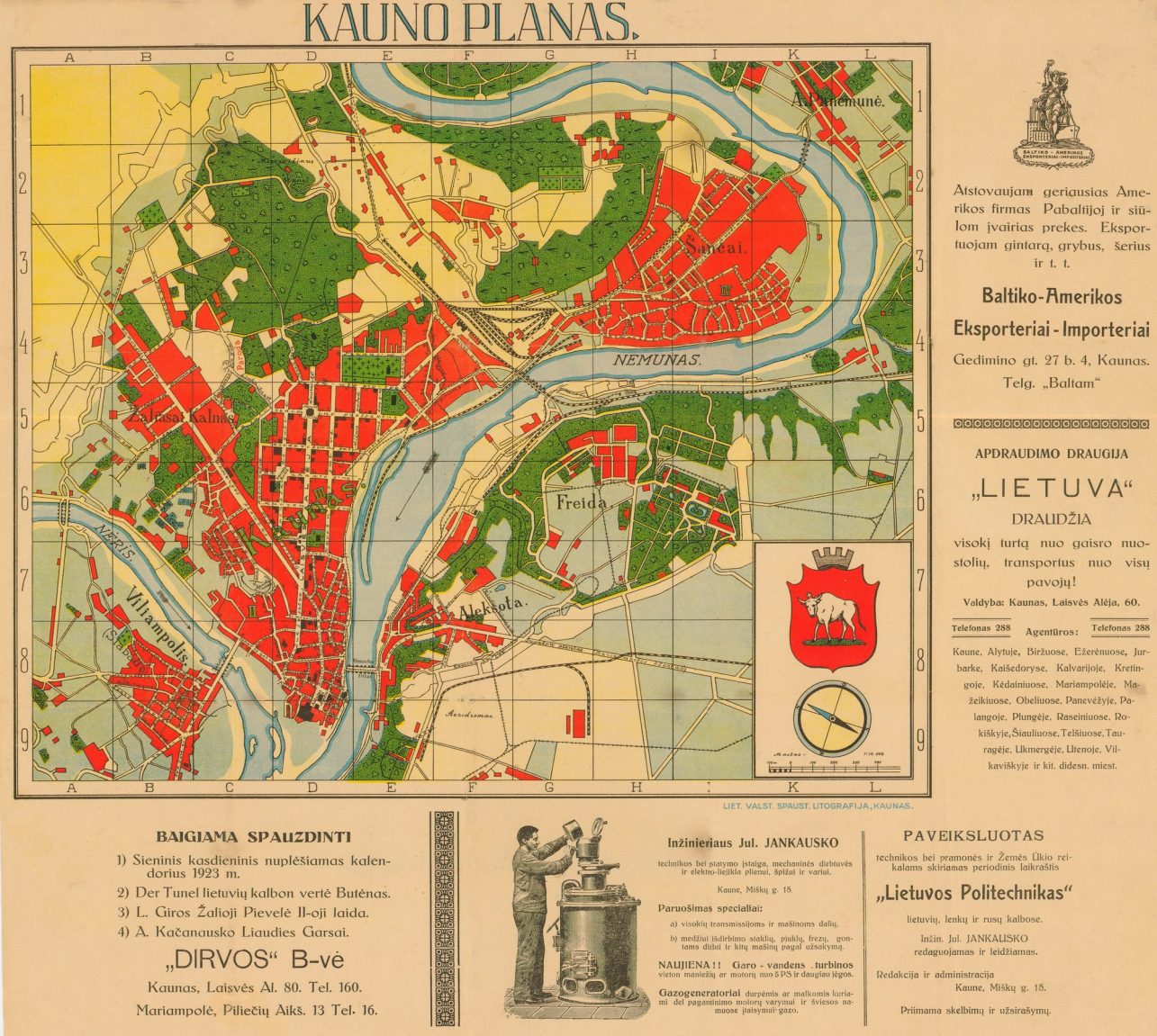

The surrounding settlements – Šančiai, Žaliakalnis, partly Aleksotas – were already connected to Kaunas at the time. Today, these districts have their own unique faces and historical identity. How did these settlements look back them? What was their ethnic and social composition? Did they all want to become Kaunas residents?

The territorial boundaries of Kaunas were not accurately determined in 1922. I did not find any reliable document in the archives that would clearly point to the precise territorial definition of Kaunas. In 1918s, in addition to the city’s core areas, residents from Aleksotas, Vilijampolė, Žemieji Šančiai as well as Žaliakalnis participated in the municipal elections of Kaunas city. Many of the inhabitants of these suburbs worked in the central part of Kaunas and were closely linked with the city. Owners of real estate in the suburbs were rather upset with the fact that their estates became part of Kaunas city because the tax burden increased and various obligations to the city grew. Being part of the city meant more obligations.

Many Jews lived in Vilijampolė and the Old Town. Žaliakalnis had a large Polish-speaking population (especially in the western part). There were quite a few Germans living in Žemieji Šančiai (they built Evangelical Baptist and Methodist churches there). We could say that probably the most Lithuanian part of Kaunas in 1922 was Aleksotas. A relatively large number of Lithuanians lived in the Carmelite district (the surroundings of the current shopping and entertainment center Akropolis) and in Žemieji Šančiai (mostly factory workers).

Many of the companies that later grew significantly were established in Šančiai. What made this part of the city attractive to businesses? I have recently read that, for example, in Vilnius, leather workers gathered around Lukiškės, and breweries concentrated around Antakalnis. Maybe similar patterns could be observed in Kaunas?

There was a large metal processing company in Žemieji Šančiai: the brothers’ Schmidt Vestfalija factory (founded in 1879). In the interwar period, it was purchased by brothers Jonas and Juozas Vailokaitis. The factory continued to manufacture metal products. Ringuva company settled in Žemieji Šančiai in 1920. It manufactured oil and later soap. Lithuanians returning from the United States established the joint-stock company Drobė, which opened a broadcloth factory.

Žemieji Šančiai were attractive to industrial companies because there was a railway nearby, many workers lived there, and there were no issues with the transportation of raw materials and products as well as no shortage of workers. Šančiai – surrounded by the Nemunas from three sides – were ideal for the wood processing industry. It was convenient to pull logs from the river and process them in the nearby workshops.

Speaking of the interwar architecture, we keep mentioning that the architects studied in St. Petersburg, the younger ones in Rome and Germany and brought their experience to Lithuania and Kaunas. But how were the builders prepared for that construction boom that started a little later? Has it always been a popular profession? Or maybe you had to import the workforce, as businesses do now.

In the early 1920s, there was a shortage of architects, engineers, and construction technicians. Architects came to Lithuania even from Switzerland, for example, Eduardas Pejeris. There were not many builders capable of performing complex construction work, and they were in great demand. There was no shortage of ordinary builders for low-skilled jobs. There were many low-skilled workers in Kaunas who worked part-time in construction. The pay was higher than in agriculture, so those men who knew something about construction and were physically resilient, tried to get a job in construction during the warm season. During the winter season, when these jobs stopped, construction workers often had to live from the money they made during the summer.

The Higher Technical School was opened in Kaunas in 1920. It also prepared the construction specialists. Ordinary builders usually learned their craft from an early age by working in construction (starting with unskilled work) or in various trade schools.