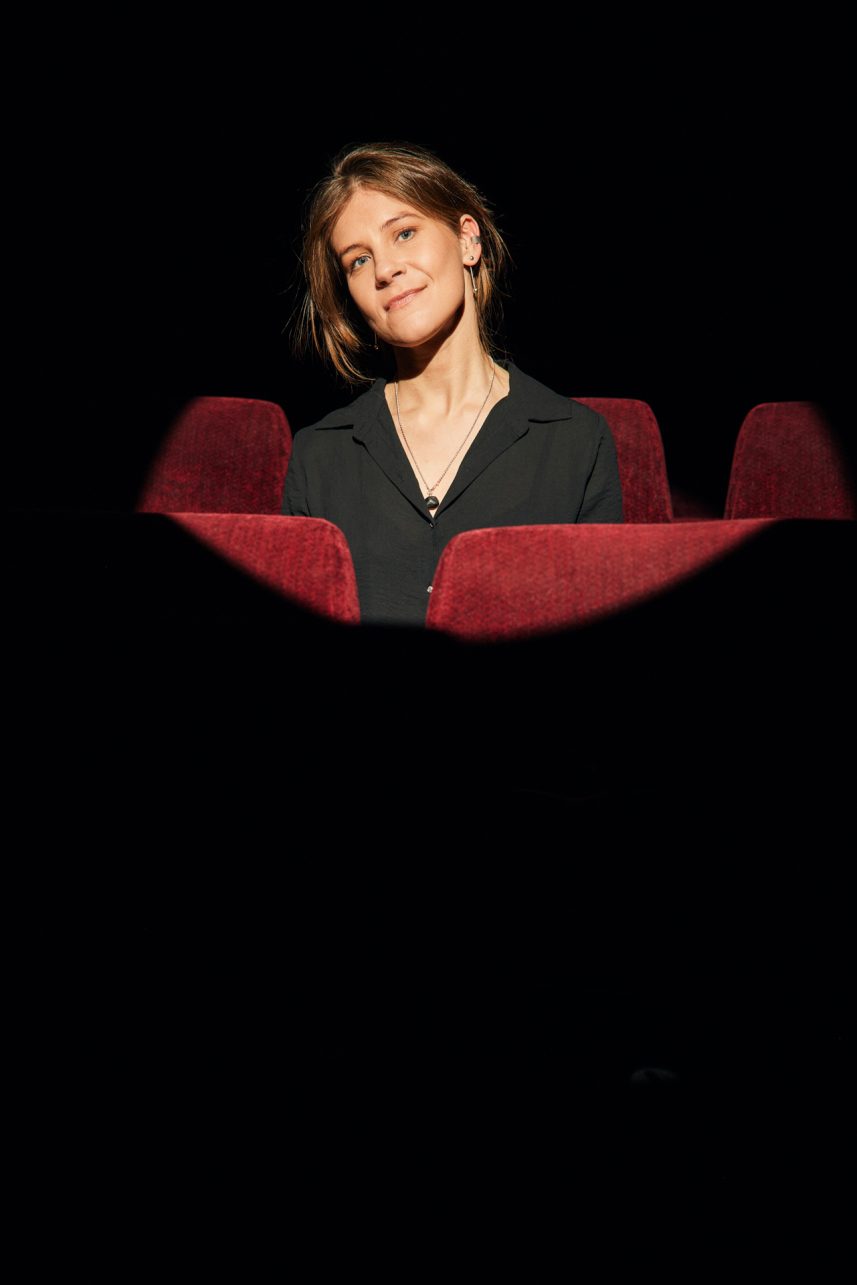

“Cinema is an extremely reactive medium,” Aistė Račaitytė, head of content and program of the Vilnius International Film Festival “Kino Pavasaris”, begins our conversation.

When discussing the program of the festival that will take place on March 16 – 26, we found more than one piece that helps us understand what it means to be that ‘other’. Aistė says that cinema is always full of painful, uncomfortable topics because the stories you see on the screen always need drama. It doesn’t matter what the viewer’s views are; they experience whatever the protagonist experiences. They recognize themselves and thus rethink relevant issues. To create intrigue and drama, there must be a conflict, and there is plenty of it in everyday life. So, what manifestations of a relationship with the other – someone less familiar – along with the consequences and empathy training will we find in the festival program, which returns for its 28th spring and will be shown in both Romuva and Forum Cinemas Kaunas this year?

One film I would like to discuss is Bread and Salt by Polish director Damian Kocur. It is based on true events and tells the story of a pianist who returns to a small town. A guy living in the capital who will soon go to study in Germany is more open to the world than his old friends. Still, when communicating with them, he seems to identify with them, does not show his more liberal views, approves of xenophobic jokes, and does not prevent the tragedy that began with an altercation at a kebab shop. I believe the film will cause an uproar in Poland, just like Clergy did. Firstly, I would like to ask why Lithuanians don’t make such controversial films. Maybe The Poet will be the closest to that.

Indeed, The Poet captures that split personality very well. This is the basis of Bread and Salt. I remember how my professor Živile Pipinytė emphasized that we should learn from the Poles and go to their films to look for answers that are important to us because we are culturally and historically similar countries. I have no doubt that a story like the one in Bread and Salt could take place anywhere in Lithuania. Perhaps a deeper tradition, a more extensive film school, and a larger scale could explain why Poles can do so. While we are on our way there, why not look for important things in the neighbour’s cinema? And controversy means success in film theatres. It is clear that Polish society is better prepared to go, talk it out, and explore complicated historical narratives and current issues.

And in terms of the protagonist’s fear of speaking out and his confusion in that group of friends, I think the film emphasizes that the transformation is not so fast. Even a mature person will not be able to withstand the pressure of the environment at all times. It’s only human. At one point you break, and you want to be part of the community, but the context starts to pull you back. Maybe you don’t feel like yourself in that new world. Maybe you nostalgically want to keep what you had before. But that retention also comes at a cost, and in the case of this story, a lot. We easily identify with such an imperfect, weak hero. We wonder what we ourselves would do differently, at what point would we say it’s enough? Cinema in this case is a comfortable exercise that brings us closer to uncomfortable topics.

The next film is Saint Omer by Alice Diop of Senegalese origin, who was making documentaries until now. The film is based on a true story. The director herself took part in the trial of a woman who killed her child. I was drawn in by that realism, the multilayeredness, and again that absence of a real hero. Both films are indeed very documentary-like in this respect.

It is unequivocally praised by critics and Alice Diop is considered one of the most promising French film stars. The film leaves the viewer with many questions. It is hard to decide how to assess the situation. The director says that everything is not black or white. You can’t judge almost anything or anyone without context, be it someone close or unfamiliar to you, or even a person on screen or in the courtroom. Saint Omer employs a documentary strategy, which is very long shots. In a documentary, a continuous shot is proof of authenticity and realness because during a montage, something is always cut out, and the possibility of manipulation appears. It is because of this technique that the viewer seems to feel suspended, they no longer understand what to think but they also cannot take their eyes off of it and get involved in that trial.

How would you comment on the movie poster in which the character on trial stands against a wooden wall, dressed in similar colors? It is as if she blends in and disappears. I thought to myself that the causes of such tragedies are invisible in society.

I was thinking about a certain aesthetic strategy. As you mentioned, Alice Diop is a director from Senegal, a black woman living in France. It’s no secret that very often film is aesthetically unsuitable for darker skin. But in this film, everything is fantastically lit. I would consider the main character’s glowing skin as bringing to light something that has been marginalized for a long time. I was completely captivated by the aesthetics of this film.

Another important aspect is preconceptions. The woman on trial is black, an immigrant from Africa. The court should not be guided by stereotypes, but even the topic of her PhD thesis is questioned, as though she should have chosen a topic closer to “her culture.” The woman’s act is attributed to some sort of tradition, magic, and rituals. It shows the fear that comes with encountering the ‘other’. In this case, she is just trying to fit into the context by delving into Western philosophy, but we prevent that.

Now, let’s get back to Bread and Salt. So, as long as you prepare delicious kebabs, everything is fine. Live and be but not more. Aistė, what else should I watch in order to continue thinking about these topics?

Cristian Mungiu’s R.M.N. The abbreviation stands for magnetic resonance in Romanian, so it’s like a magnetic resonance dissecting Romania itself. The film is about xenophobia. An emigrant returns to his native village in Transylvania; he thinks about settling here. The local factory employs immigrants from the Far East. The disgruntled community gathers to discuss because they believe that the factory should employ locals and work for the benefit of its own people. Everything turns into a tragedy. You know, maybe in the West, those situations don’t develop in such straightforward scenarios anymore, but in our region, the topic of the relationship with the other is still at a very immature stage, and that’s why the films are the way they are.

You should also watch the Italian Emanuele Crialese’s L’immensità. This is a coming-out story, a personal story of the director. An episode from a family’s life. We see a young man, who was born as a girl. But the film is more about a mother who believes in her son even in 1980s Italy when its society was traditional and patriarchal. Penelope Cruz plays the mother, a Spanish woman who moved to Italy and is also not completely accepted by those around her. That otherness and marginality become the bond that ties her to her son. The moving drama also has some elements of a musical that turn into escapist moments. Due to that otherness, that discomfort, you escape into fantasies.

I cannot wait to see documentary initiated by Vytautas Puidokas and created together with many other members of the film community. It is a film about the Lithuanian response to the war in Ukraine. I wonder if it will show any critical moments. How the Lithuanian society mobilized at the beginning of the war and yet how it ignored the issues of other people and migrants until then. Which ‘other’ is more familiar? We hear about painful reactions to being proud of the country’s success story from those people who are trying to solve problems on their own.

I could definitely continue the list. You will find this theme in more than one film of the festival. That says a lot about its inevitability.